Does it seem like the celebration of Black History Month this February was a bit lackluster?

Super Bowl ads, praised in recent years for their promotion of so-called diversity, equity, and inclusion, seemed less obsessed with the topic this year. “Super Bowl Commercials Reflect Waning DE&I Commitment in the Ad Industry,” read one headline, its author noting that “the majority of casts, crews and directors behind the 2023 Big Game commercials are white men.” Indeed, after a dramatic increase in racial and sexual minorities in 2020 and 2021, Forbes in January reported that television and streaming advertising is, surprisingly, getting whiter.

Is America approaching “diversity and inclusion” exhaustion? Has our elite establishment’s obsession with all things related to racial and sexual minorities — and, by extension, an ideology defined by victimhood narratives — made the actual celebratory events of our calendar perfunctory and less interesting? When every month seems like Black History Month, perhaps February feels less special.

Diversity and Inclusion Over-Saturation

The signs of a cultural diversity and inclusion over-saturation seem evident in lots of places. Given how aggressively grocery stores in my native Northern Virginia have recently promoted Pride Month and Asian-American and Pacific Islander Month, I expected a big celebration of black culture, cuisine, and black-owned businesses. But to my surprise, I witnessed nothing in my local grocery store to commemorate Black History Month; it was all Valentine’s Day product hawking.

I also expected a significant spike in celebration and coverage of Black History Month in The Washington Post and other corporate media. Perhaps a big insert in the print edition, or a separate section on the website. But no — the Post’s “Race in America: History Matters” series declared it would dedicate February’s programming to Black History Month, though with a series already titled “Race in America,” what exactly was different? On its website, The New York Times featured “Recent and archival articles, essays, photographs, videos, infographics, writing prompts, lesson plans and more,” to honor Black History Month. In other words, says the Times, we do this all day, every day, so just look at our past content.

In recent years, corporate media commentary on Black History Month had become increasingly shrill and hostile. “How — and how not — to celebrate Black History Month: Let’s have less virtue signaling, hypocrisy, and misidentifying of Black people this year, OK?” was the title of a 2022 column in the Boston Globe. There is a “White Leech on Black History Month,” declared Cole Arthur Riley in a WaPo op-ed last year. An opinion in WaPo the year before was titled: “I don’t need or want corporations celebrating Black History Month.” And an article last year at Education Week urged whites to avoid making themselves the center of Black History Month. Translation: You’d better celebrate Black History Month, but we reserve the right to shame you for doing it all wrong, you racist.

Every Month Is About Race and Racism

All of our elite institutions — not only corporate media, but the academy, entertainment industry, and federal government — obsess over race, racism, and racial grievance all year long. As I recounted in a 2021 article for The Federalist, just open any major newspaper, visit any legacy media website, and you will find stories and opinions about race and racial grievance. The recent dustup over Florida’s resistance to the rollout of the new Advanced Placement African-American Studies curriculum obscures the fact that the entire AP humanities curriculum is already prioritizing content on racism and racial grievance, and that millions of students are already being taught an explicitly anti-racist curriculum thanks to the 1619 Project and Southern Poverty Law Center.

The entertainment industry has been foregrounding anti-racist narratives in movies and streaming programs for years. Prominent musicians such as Taylor Swift and Beyonce, as well as music industry executives who pay them, regularly denounce racism and pay homage to the gods of equity. The current presidential administration is the same: White House Press Secretary Karine Jean-Pierre in late February crowed, “The cabinet is majority people of color for the first time in history. The cabinet is majority female for the first time in history.”

In effect, in Eliteland, every month is Black History Month, except maybe May, when it must take a backseat to Asian-American and Pacific Islander Month, and June, Pride Month, which is quickly becoming the most aggressively promoted event in the country. Though even with these, there’s no reason why we can’t do both. “What’s Beyond Pride Month? Black Pride,” declared a 2022 Boston Globe story. “The Black and brown activists who started Pride,” reads a 2021 article by Brookings. According to a 2022 USA Today op-ed, even Asian-American and Pacific Islander Month is an opportunity for us all to reflect on — you guessed it — racism against black Americans.

Trading Hope and Brotherhood for Cynicism and Distrust

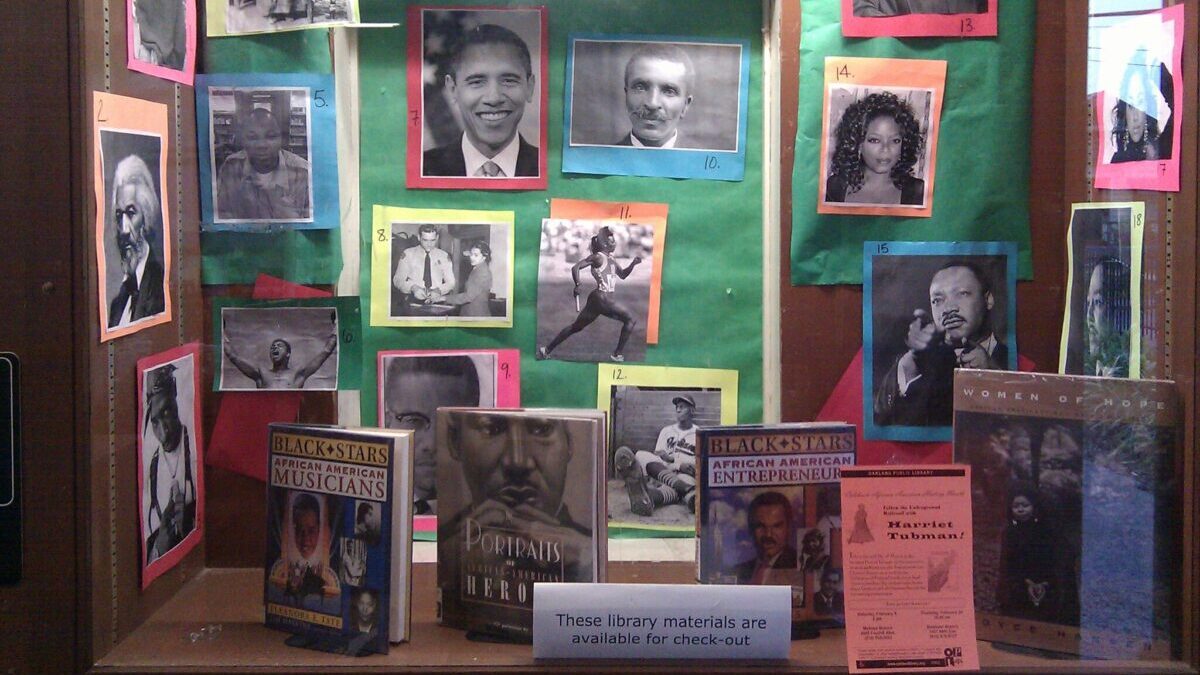

I fondly remember celebrating Black History Month in the 1990s as an elementary school student in Northern Virginia, in the same county in which my grade-school-aged mother had experienced desegregation in the 1960s. Posters in classrooms and hallways celebrated black heroes of our nation: Frederick Douglas, Harriet Tubman, George Washington Carver, Jackie Robinson, Martin Luther King Jr., and, one of my favorites, Mary Jane McLeod Bethune, whose euphonic name I never tired of hearing. My mother had a Neville Brothers’ cassette tape with a song honoring Rosa Parks, which as a fourth-grader I played for my classmates.

I remember learning plenty about slavery and segregation, but never in a way that made students feel either victimized or cynical (or, alternatively, guilty). We weren’t told our nation’s checkered history on race defined our national present or future. Nor did I feel that way, or tell students to feel that way, when I taught U.S. history in Fairfax County after graduate school.

Now, it seems, many folk don’t even know what to do with Black History Month. They’re encouraged to celebrate it, though sometimes, confusedly, they are simultaneously discouraged from celebrating it. They’re told it’s a special month to honor the accomplishments of black Americans and to consider the trials they’ve faced in our nation’s history — which sounds exactly like what we’re told to do every other month of the year.

When we enter March, will the news, opinions, entertainment programming, or political messaging actually change? I’m not sure anyone can even tell. Moreover, the narrative we are given is no longer an uplifting one of a shared, redemptive national story, but one of grievance and victimhood that engenders cynicism and distrust between citizens. No wonder the national celebration of Black History Month this year felt subdued. Cynicism tends to exhaust people.