Silicon Valley venture capitalist Tim Draper has come up with a scheme to split California into three states, and he’s collected twice as many signatures as he needs to get the proposition on the ballot in November. Some 600,000 Californians have signed his petition, which would allow a vote on whether to split the state into North California, South California and California.

Personally, I would have named the third part Coastal California. Here’s what Draper has in mind:

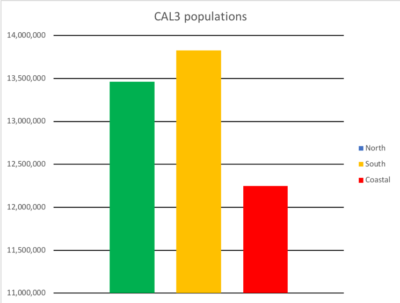

He has done one thing correctly. He has roughly equalized population among the three regions in his proposal. The effect, however, would be to syphon all the conservatives off into one state — South California — and create two progressive states. In other words, progressives would get four U.S. senators and conservatives just two.

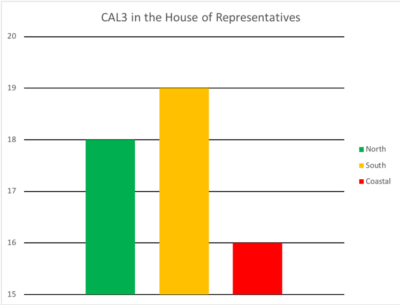

What about the House of Representatives? Excluding states that only get one representative as well as the District of Columbia, which gets zero, each member of the House represents 705,524.19 people. That makes it easy to calculate House membership under Draper’s proposal. North California would get 18 members, South California 19 and (Coastal) California 16.

Curiously, the conservative state would get more representatives than either of the other two. But note the total of 34 progressive representatives to 19 conservative representatives. (These figures assume total representation in the House would equal California’s current 53 members.)

As For Gerrymandering

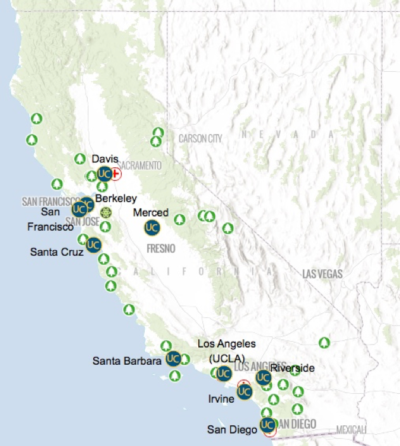

Pay close attention to the map. Note that Orange County and San Diego County are lumped in with the conservative farming areas of the Inland Empire. While this equalizes the population, it removes a large conservative component from the Coastal California state. In fact, Orange County and several of its cities have sued the state to be allowed to opt out of the “sanctuary state” status that has been declared by Sacramento.

Whether intentional or not, this would slightly change the balance in the Electoral College. Each state’s representation is equal to the sum of its senators and representatives in the House. California’s current Electoral College representation is 55. The proposed new state would add four new senators, bringing the total to 59. While this usually would not cause a change in the overall vote, it could conceivably make a difference.

California currently has 14 Republicans and 39 Democrats in the House. The problem is that CAL3 divides the state using counties as the unit of measurement. But congressional districts do not conform to county lines. For those unfamiliar with all of California, here are a few examples. CA1 covers the northeast part of the state. It includes nine counties (Siskiyou, Modoc, Shasta, Lassen, Tehama, Butte, Plumas, Sierra, and Nevada). It’s an understatement to say that region is sparsely populated. By contrast, Los Angeles county alone is home to 17 districts. About the only thing we can be sure of is that, if CAL3 passes and the state is eventually divided, there will be massive gerrymandering to try to get the districts the way whichever party controls the state wants them.

What Happens if CAL3 Passes?

CAL3 can be passed by a simple majority in November, if it is put on the ballot. If it passes, the state legislature will have to approve the request to divide the state and the governor will have to sign the bill. After that the request must be approved by the U.S. Congress. I personally doubt that either party in Washington, D.C., wants to take a chance on upsetting the balance of power. But it wouldn’t be the first time the idea has been tried.

There have been seven previous attempts to break up the state. The first, the Pico Act of 1859, would have split off all of the state from (roughly) San Luis Obispo south. The legislature approved it, the governor signed it, and it got a whopping 75 percent of the popular vote in southern California. But the U.S. Congress is also required to approve splitting a state, and in this case an inconvenient event called the Civil War distracted the Union Government from the relatively minor matter.

But the Jefferson Rebellion is far more interesting, if only because there have been repeated attempts to form the state of Jefferson. In late 1941, a group of ranchers from southern Oregon and northern California declared that the two regions would be joined to form the state of Jefferson. Both groups felt they were largely ignored in the capitals of each state.

But the original rebellion dates to the mid-19th century. The motivations, however, remain much the same. These two regions are very rural and have more in common with each other than with the rest of each state. I won’t go into details here, but Casey Michel has a rollicking account at Politico.

Breaking Up Would Be Hard To Do

For starters, there would be three state governments. Each would have its own departments: education, transportation, public safety, and so on. This is the inefficiency drag. Whether the improved proximity to voters in each state will be enough to offset those costs is very debatable.

For example, the California Department of Transportation (CalTrans) is currently responsible for construction, repair, and maintenance of highways in the state. Here’s how that agency’s website describes its job: The California Department of Transportation (Caltrans) owns or controls 350,000 acres of Right of Way and maintains 15,133 centerline miles of highway and 13,063 state highway bridges. Caltrans also inspects more than 12,200 local bridges.

The agency divides the state into 12 districts. Naturally these do not conform to either congressional district or county boundaries (although only Butte, Kern, and Sierra counties are split between two districts).

So here’s how it would break down. Northern California would get districts 1, 2, 3, 4, 10 and the northern bit of 5 (basically Santa Cruz county). Coastal California gets the rest of 5 plus 7. And South California gets 6, 8, 9, 11, and 12.

While it’s tempting to look at the number of miles of highways in each new state that the transportation agency would have to manage, that’s a fool’s errand. Eastern California (at least down to King’s County) is home to some of the heaviest snowfall in the U.S. Currently the base at a Lake Tahoe ski area is 400 inches. The northwest part of the state is subject to heavy rain. In fact, Del Norte county gets an average of 132 inches of rain per year. Contrast that with Imperial’s annual average of 3 inches. Southeastern California is home to the Joshua Tree National Park, Death Valley, and a lot of desert. Add to all that the varying degrees of earthquake risk in various areas, and it’s easy to see that highway miles alone would not be a good predictor of likely costs.

Colleges and Universities

California is home to three public college and university systems: the University of California, the California State University, and community colleges. The UC system has ten campuses: North California would get five, Coastal California two, and South California three. Would Los Angeles and Santa Barbara go along with that? In addition, the UC system has six medical centers, two national laboratories, and a host of other activities. What a mess.

But it gets even worse when you consider the CSU system. North California would get nine (Stanislaus is located northwest of Merced). South California would get four, while Coastal California would get ten. Those who live in the Inland Empire and Orange County would not be happy.

There are 114 campuses in the California Community College System. I leave it to readers with way too much time on their hands to perform those calculations.

In sum: CAL3 is a dream come true for politicians, consultants, lawyers, and accountants. There would also be plenty of work for surveyors and experts on geographic information systems. Each of these professions would find their services in high demand if this proposal passes and is approved by the Congress.