By now you’ve probably seen this well-researched article by Arielle Pardes in Wired, discussing the rise of the experiential, selfie-oriented exhibition in the contemporary art world. Pardes’ article asks some good questions about how social media sharing is affecting art, and questions whether blurring lines between artist and viewer is creating a new form of art in itself.

At the same time, many art institutions are torn between the potential advantages of digital mass media, and the lurking dangers its use poses to both their collections and to art appreciation overall. Trapped somewhere in the middle are those of us who just want to go see a work of art without being blocked by someone else wobbling about with his mobile in front of it.

The concept of art patrons directly interacting with art, in which the viewer temporarily becomes part of the piece itself, is not exactly new: Claes Oldenburg’s “Lipstick (Ascending) on Caterpillar Tracks” (1969) at Yale comes to mind. Social media takes that interactivity to a different level, however, so that all art is capable of becoming part of our own online persona and self-marketing.

In fact, there are many current examples of art specifically designed to end up on Instagram as part of a selfie, such as the immersive, Instagram-oriented experience of The Museum of Ice Cream’s New York show Pardes references, flavors of which have since been offered in Los Angeles, Miami, and San Francisco.

The increasing popularity and acceptability of the selfie-oriented art show may have something to do with shifting opinions on the value of our cultural institutions. In a recent study sponsored by CultureTrack, a majority of those surveyed said social media advertisements had a greater influence on their choices to visit cultural events like art exhibitions than did traditional print ads. In other words, if you’re an up and coming artist putting on a show of your latest work, these days you can get more people through the door via a successful Instagram campaign than you could through speaking with The Art Newspaper or The Guardian.

Loving and Hating Attempts to Stay ‘Relevant’

British street artist Banksy for example, whose inexplicable rise in the art world stems primarily from his appropriation of the tools inner-city artists use to express their suffering, via his own rapidly dating chav/yoof culture, hardly ever communicates directly with the press. In fact, he hasn’t even given an in-person interview in almost 15 years.

Yet I would venture to guess that most plugged-in millennials on the planet not only know Banksy’s work, but have an opinion about it, thanks to what they are able to see, hear, and read in social media. Like many contemporary artists, Banksy doesn’t need the art world establishment to make his work desirable, while the art world is desperate to forge a connection with him and artists like him to stay relevant.

As part and parcel of that attempt, a number of cultural institutions have developed a love/hate relationship with the ubiquitous “selfie,” a cultural phenomenon that can prove both beneficial and risky to artists and galleries. The desire to share one’s experience when visiting one of contemporary artist Yayoi Kusama’s “Infinity Rooms,” for example, by posting pictures of yourself and your friends within the exhibition space, has led to some critics to question whether the artist is simply pandering to our narcissistic, Kardashianized age.

The New York Times’ Roberta Smith for example, recently described Kusama’s use of the designed-for-Instagram conceit of filling a room with mirrors as behavior bordering on that of the “charlatan.” While finding much to praise in Kusama’s paintings, Smith opined that the artist “stoops to conquer with mirrored ‘Infinity’ rooms that attract hordes of selfie-seekers oblivious to her efforts on canvas.”

Both artists and institutions have realized the superior ability of a selfie, when successfully shared across social media platforms, to capture the attention of a far wider audience than even the most well-written exhibition review in a magazine or newspaper. Many cultural institutions will even suggest what hashtags to use when tweeting or posting a video, to achieve maximum exposure both for the poster and for the institution, accepting that the selfie is a fact of life for the foreseeable future.

In speaking with curator Nora Atkinson at the Renwick Gallery, Emily Matchar notes in Smithsonian Magazine that many institutions such as the Renwick have simply accepted the selfie as an inevitability, even if they try to encourage visitors to stop looking at their screens and start looking at the art in front of them. “It’s impossible to prevent [photo-taking],” Atkinson explains, “so why not get with the program and the 21st century and allow it as much as you can?”

Selfies’ Direct Danger to Art Objects

That open-armed embrace of the selfie, however, is not characteristic of the art world as a whole. Last summer, when visiting the massive palace of El Escorial outside of Madrid, which houses an art gallery containing a vast number of paintings, sculptures, and decorative arts from five centuries of Spanish royal collections, I asked a docent whether photography was permitted.

She replied that it was only allowed in the exterior spaces, but thanked me for asking because she and the other museum employees must constantly stop visitors from backing into fragile works of art while attempting to take selfies. I’ve heard similar tales of employees having to tangle with careless, screen-obsessed visitors at other institutions, such as at the very strict Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston, where I dare you to even try pulling out your phone once inside the galleries and see what happens.

Increasingly however, even the most permissive of institutions are banning selfie sticks, and for good reason. Not only are they distracting to other visitors, they can also encourage even more reckless behavior, as visitors jostle for position to capture an image of themselves standing in front of a particular object. The Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Museum of Fine Art in Boston, and the National Gallery in DC are just some of the increasing number of museums and galleries that have expressly prohibited selfie sticks on their premises.

Yet banning the selfie stick doesn’t entirely alleviate the risk selfies cause to the art on display. News stories abound of visitors knocking over statues or tearing holes in paintings as they maneuver to take the perfect selfie. One recent example from Los Angeles involved a woman who crouched down next to the first in a line of plinths displaying part of an art installation, and fell on her backside. In the process, she knocked over the display in a gut-wrenching domino effect that was caught on security camera, causing $200,000 worth of damage.

Learning How to Go to an Art Museum

In response to the Wired article referenced above, a correspondent wrote: “I’ve started taking my kids to museums a little more regularly, and when I first started taking them, I realize that they have to learn HOW to go to a museum: how to stand still, and go through things systematically, and read and observe. Rule number one of how to go to a museum is: turn off your d-mned phone. Because the people going there to take selfies are doing none of the things I just described.”

It can be difficult not only for parents of rambunctious children, but also for adults whose attention spans have been dramatically shortened by their mobiles, to be able to visit an art exhibition. They may not understand how to navigate it, nor how they’re supposed to behave once actually inside. With the rise in social media-oriented art shows, the artist and the exhibitor not only accommodate, but in fact encourage a kind of anti-social behavior that borders on the sociopathic. Therein, I think, lies the problem with the concept of an art show designed to serve as little more than an IG filter.

As interesting or amusing as it might be to post a boomerang of yourself falling into a giant ball pit posing as a work of art (and giving yourself a bad case of pinkeye in the process), the majority of art exhibitions that open each year in this country are not designed for selfie taking, nor should they be. As the name implies, there is something inherently selfish about the selfie, and as someone who certainly takes them, I know how easy it is to slip into the false belief that they are always acceptable.

They are not. Not only do they disturb others, who may not be as interested as your followers are in seeing you kiss your love interest of the moment in front of a Rodin, but they take the focus away from what you ought to be doing in the first place: looking at the art.

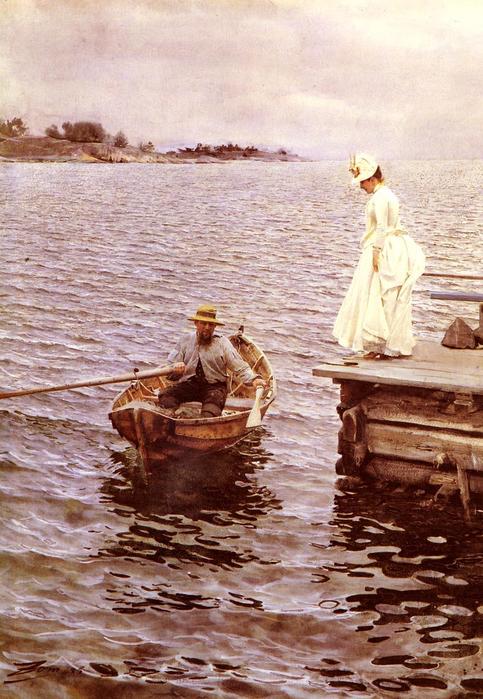

Unlike a 30-second “stories” video, or a disappearing chat, a work such as the one pictured below, by the great Anders Zorn (1860-1920), is meant to be savored, over time, not merely sampled. “Sommarnöje” (“Summer Delight”), which currently holds the record for the most expensive Swedish painting ever sold ($3.3 million in 2010), is an 1886 watercolor showing the artist’s wife getting ready to step off a dock into a rowboat that is just pulling up underneath.

There is so much to admire here, from the texture of the wood and the reflective choppiness of the water, to Zorn’s billowing linen skirts and the dramatic foreshortening of the rower’s left arm and oar, that you need time to take it all in. In fact, you might not even notice, until someone points it out to you, that the picture appears to be almost monochromatic in grays, blacks, and whites, but on closer inspection, some of those passages don’t actually have any gray, black, or white in them.

So to the parent who expressed frustration at the selfie-obsessed patrons one regularly sees at museums these days, I say: choose your battles. If you want to take the kiddos to a contemporary art exhibition in which visitors are encouraged to become part of the art, then do so. But if you want to teach your children, and indeed yourself, how to recognize beauty, genius, and transcendence in art, turn off the phone, and forget about taking a selfie inside the galleries.

Chances are, selfies are not permitted anyway, but even if they are, looking at a great work of art should invite you to share that experience with others in the best way possible: by talking about it, rather than trying to capture a fleeting image of yourself or someone else partially blocking it.

Correction: The Culture Track poll results cited above were in the initial version of this article attributed to social media posts rather than social media advertisements. The text has been corrected to reflect the poll findings.