“Does a state violate the First Amendment’s Free Exercise Clause or Free Speech Clause when it punishes a judge who has discretionary authority to solemnize marriages because she states that her religious beliefs preclude her from performing a same-sex wedding?” That’s the question Judge Ruth Neely from Pinedale, Wyoming, wants the Supreme Court to answer.

On August 4, she filed a petition with the Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS), asking them to review a March 7, 2017 ruling from the Wyoming Supreme Court. That ruling handed down a public censure and effectively removed her from a circuit court magistracy for answering a reporter’s question.

Each year about 10,000 such petitions are filed. Of these, only about 80 cases will be heard. But Neely’s petition already stands out above the crowd, giving her a far better chance than most.

That’s because SCOTUS does not usually take cases merely because a lower court got it wrong. They tend to take cases that fill three requirements. First, the case should be clean and uncomplicated. Second, they address important and emerging questions of constitutional law. Third, cases they take must have nationwide and far-reaching implications. Neely’s case scores high on all counts.

All Neely Did Was Answer a Hypothetical Question

Cases as clean-cut as Neely’s rarely come before the Supreme Court. There is only one fact that underlies the whole case, and this is not under dispute, but freely stipulated by both sides: On a Saturday morning in early December 2014, in answer to a direct question, she told a reporter she was unable to perform same-sex weddings because of her religious convictions.

The whole thing boils down to those words, and those words alone—spoken outside of business hours and outside of the courtroom setting. Neely did not then, nor any time since, take any official action towards a same-sex marriage. Nor has she ever spoken again on the issue.

Over the course of the last 33 months she has turned down numerous speaking invitations and remained mute on the subject. This self-discipline now helps to make hers one of the cleanest cases possible. There is one conversation between herself and one reporter, and nothing else to muddy the waters. If you want to isolate the question of free speech and free expression, it cannot get any more isolated than that. Score one for Neely.

This Is Also Cutting-Edge Constitutional Law

As for emerging constitutional law, Neely’s case is on the cutting edge. The telephone conversation with a reporter happened more than six months before SCOTUS voided marriage law across the United States with the Obergefell v. Hodges opinion, but she anticipated a question that would arise in its aftermath.

What prompted the reporter’s phone call was the case of Guzzo v. Mead that brought same-sex marriage to Wyoming by vacating Wyoming marriage statute (20-1-106). By the fall 2014, four federal circuits had struck down marriage laws within their jurisdictions, but none had spelled out the specifics of what should replace them.

Changing marriage law is not like changing the speed limit. Speed limits are a balancing act between individual freedoms and public safety. Marriage law is about the very foundations of human existence. While there is a reasonable compromise between 60 and 70 miles per hour, there is no halfway ground between a sexual understanding of marriage and an asexual understanding of marriage.

So the question Obergefell has raised across that land is this: can we craft laws that permit the peaceful coexistence of mutually exclusive views? Or must the disfavored view be driven out of public life altogether?

Banning Faithful Christians from Public Life

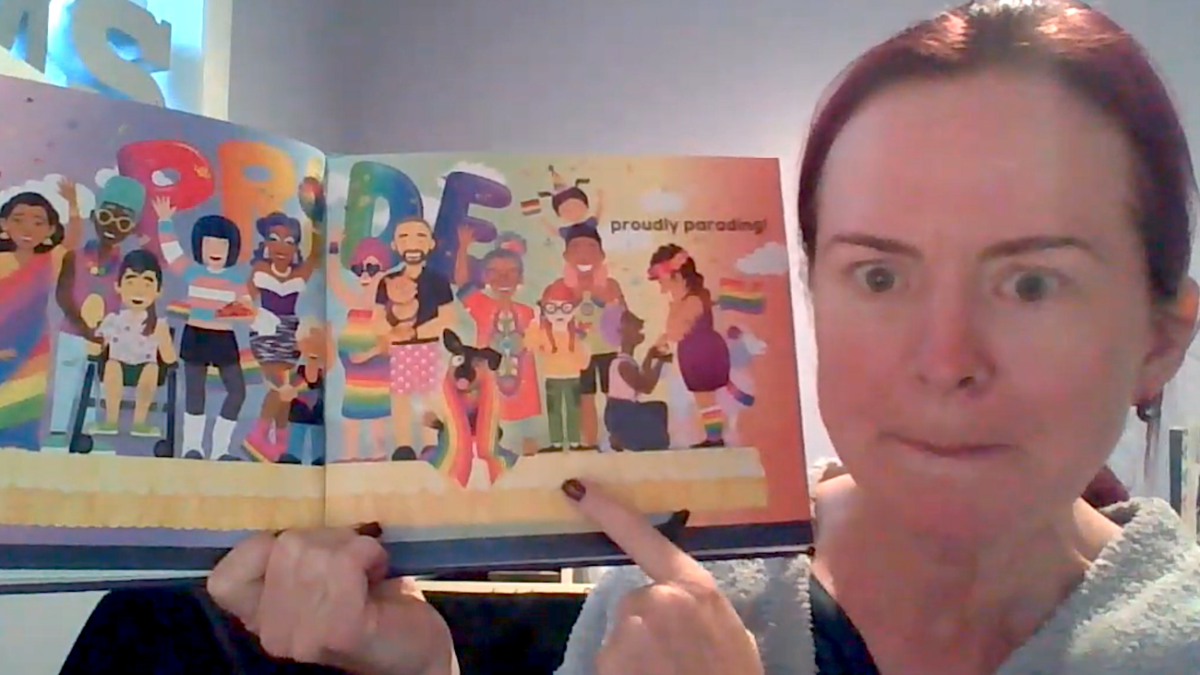

Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity (SOGI) rules, which the American Bar Association has pushed on the judicial ethics commissions of numerous states, have the predictable effect of driving anyone with a sexual understanding of marriage out of government service.

Neely’s case is not the only one of this type. Under similar rules in Washington state, Superior Court Judge Gary Tabor was “admonished” by the Commission on Judicial Conduct for publicly announcing he would not perform any same-sex marriages. As part of the discipline, he effectually agreed to perform same-sex marriages if he were to perform any at all. While this case largely slid under the radar, Neely’s case has raised the issue to national attention. It is time to address this question head on.

Such gag orders and compelled speech are driving people out of government service either directly, or by the mere threat of sanction. Should SCOTUS allow this trend to continue it would set a dangerous precedent for the future of any group with a disfavored view.

If You’re a Judge, You Can’t Voice Your Opinions?

Finally, the far-reaching implications of the Neely case are hard to overstate. The Wyoming Supreme Court, guided by SOGI theory, assumed that every Wyoming judge must, without exception, not only recognize the legality of same-sex marriages (which Neely does), but also personally perform them. This, despite there being no written law, anywhere, which requires this.

But the court went farther still. They next asserted that any judge whose speech questions this unknown and unwritten law is, by the mere act of speaking, undermining “public confidence in the judiciary.” If a judge can be censured and removed merely for speaking disagreement with an unwritten law, what would prevent any judge, anywhere, from being punished and removed for speech disagreeing with any actual law or constitutional provision?

Is it constitutional to remove a judge who merely speaks in favor of removing the right to keep and bear arms? Should all those judges who publicly favored same-sex marriage before Obergefell vacated the laws of most states have been censured and removed? What about judges (either pro-life or pro-abortion) who openly acknowledge that Roe v. Wade was a legal abomination? Shall they be purged from our courts?

These questions are not just rhetorical. They are real. Wyoming’s censure of Neely opens the door to these absurdities and many, many more. It is high time we step back from the brink. Neely’s petition gives SCOTUS an opportunity to take in the big picture. What we do today will have far-reaching implications for the free speech of all public servants, and all citizens in general, long after same-sex marriage recedes into the footnotes.