Remember that time you heard a great piece of advice?

Maybe a favorite blog picked up on a fresh, new medical or psychological study. Maybe a choice quotation, a few words of ancient wisdom, caught your attention. Whatever it was, you resolved right then and there to put the advice into practice. You set out to reform your ways and turn over a new leaf. You felt invigorated and determined.

Remember how you then failed to follow through?

We’ve all been there. A friend e-mails a neat article on time management; researchers report that sitting all day is the health equivalent of chain-smoking while pounding tequila shots; a podcast extols the virtues of mindfulness meditation; a pastor delivers a killer sermon or homily; a new job or school year brings a new opportunity to stay organized. These crystal-clear moments of energy and resolve are not infrequent. Much rarer, it seems, are the times we really implement the change we seek.

Three principles can help. And they are as relevant for political change as for our personal lives.

1. Remember How Much Life Circumstances Matter

Part of the reason for our lapses is understandable. The same patterns, structures, and lifestyle contours that help form a rut are still there even after we make up our minds to escape. We imagine new versions of ourselves that lie on the other side of an inflection point, but forget that everything about our daily lives has slowly built up around us not being that kind of person. Just because our thinking has shifted doesn’t mean anything else has.

Say you want to carve out more regular time for prayer or meditation. That’s a noble impulse, but it doesn’t erase all the other habits that have gotten in your way to date. That affinity for late-night TV, that love affair with the “snooze” button, and that reflexive refreshing of your Twitter timeline are well-worn habits. These routines comprise our default position; they’re the course our autopilot will chart if we don’t intentionally steer somewhere different. They’ll take more than a 30-second epiphany to unravel.

Some psychologists and lifestyle gurus advise us to make our changes as small and incremental as possible. But, thanks to this phenomenon, I think their arguments are frequently overstated. Often, the changes we seek can’t be made by chipping away at one isolated behavior or habit. We have to tackle a whole network of related behaviors at once. If we really want to lift weights three times a week—and make it a productive experience—we must also shift bedtimes, eating habits, and so on. In short, we need to change our baseline, the backdrop against which our goals will need to occur.

This principle is not only important for personal change. It has ramifications for public policy. Amidst heated debates over whether Congress should fund an individual project, we often forget that fully two-thirds of federal spending is “mandatory,” or spent on permanently authorized programs that don’t need to be reauthorized to remain in effect. A subset of this mandatory spending is even funded automatically. These “automatic” programs, including Social Security and parts of Medicare, are essentially bills Congress has set to auto-pay. The boulder just rolls along under its own momentum unless deliberate efforts are made to slow it down.

Given this reality, trying to achieve fiscal discipline by slashing shiny-object programs like foreign aid is like trying to change your overall, year-round health by foregoing one piece of pie at Thanksgiving. It’s the picture of futility. All those infamous, insane-sounding examples of pork-barrel spending are just tiny fractions of a category called non-defense discretionary spending, which makes up a little more than a tenth of the budget. We need to change our baseline. We need to shift the tectonic plates that make up the ground on which those tiny battles are fought.

One-off bursts of willpower are vastly overrated. To make meaningful change, work to shift standard operating procedure. Aim to lock in a better trajectory.

2. Grown-ups Shouldn’t Always Take ‘Baby Steps’

We hear a lot about “baby steps,” but making one tiny tweak at a time can go badly wrong. The “tyranny of small decisions” is real. Evaluating each separate choice in isolation can produce perverse results. If you’re exhausted from staying up too late, it is actually a rational decision to sleep in and abandon plans to exercise. But that individually sensible choice reinforces a negative cycle. It takes you one more step farther from where you really want to be.

As I’ve written about before in these pages, this is equally true in politics. Environmental degradation, suboptimal suburban sprawl, and the thicket of overregulation that encroaches on free enterprise all manifest the heavy costs of shortsighted practicalism. Doing the ostensibly pragmatic thing a thousand times in small matters is no substitute for big-picture prudence. The two roads often lead in opposite directions.

Think about how badly life would go for a purely situational rationalist. Even if you’ve successfully set aside an hour, even if your running shoes and favorite shorts neatly laid out, and even if the weather is cooperating, the health benefits of one 20-minute jog likely pale in comparison to the short-term hedonic gains of chips plus guacamole plus couch.

In their provocative book “Nudge,” Cass Sunstein and Richard Thaler describe this cognitive dissonance as a “fierce battl[e] between the Planner and the Doer.” The Planner in each of us has long-term aspirations, but it’s the Doer who grapples with each situation as it comes, and he or she is rarely down with the course of action the Planner imagined.

How can we change this dynamic? Thaler and Sunstein put their trust in a trendy field of study called “choice architecture.” They say we can escape the tyranny of small decisions if powerful people would more intentionally design the world around us. So they call for leaders to reorganize everything from government forms to supermarket shelves, focusing their elite intelligence on “nudging” the commoners towards the choices they deem best for them.

That might sound like a good idea to you, or it might sound a bit Orwellian. It’s no surprise that Sunstein, a famous friend of President Obama, would place his trust in massive institutions and top-down policy solutions to do the heavy lifting on our behalves. But whatever your view of Sunstein’s ideas, the good news is that we need not wait around for powerful people to take his advice. If we change our thinking, we can escape the trap of small thinking ourselves and act with more intentionality.

3. Stop Doing and Start Being

For a long time, moral philosophers were obsessed with asking whether specific behaviors and actions were right or wrong. They tried to craft careful rules for behavior and delved into complicated, legalistic descriptions of what actions could be justified. A good person was simply someone who did good actions, and vice versa. Behavior, not character, was primary.

But in the mid-twentieth century, a vocal group of thinkers realized this approach had gone off the rails. They preferred the way that ancient thinkers like Aristotle approached ethics, which saw character as primary and behavior as secondary. The morality of an action may vary with circumstance and available alternatives, after all—but the morality of a person can be built up over time. Prudence, justice, temperance, and courage: these are unobjectionably the traits we aim for, and we tend to know such characteristics we see them.

This school of thought (called virtue ethics) tells us our main job is not to obsessively evaluate each action. Instead, we are called to imagine what kind of person we want society to be populated with, and what kind of person we ourselves want to be. What personal virtues do we aim to cultivate? Which vices should we erase? We are told, in short, to stop asking, “What should I do?” and start asking, “Who should I be?”

This what-to-who shift can transform the way that we make our decisions. The “what” questions can seem tricky and appear like close calls, but the “who” questions often give clearer counsel. The next time your alarm goes off on a cold day, stop trying to bootstrap a complicated cost-benefit analysis of hitting the gym (“What should I do in this moment?”). Instead, ask what kind of person you want to be. On one level, this is easy: Do you want to be in shape or not? But the question runs deeper. Do you want to be the sort of person who makes excuses, or the sort who grits his teeth? Are you someone who is easily dissuaded from commitments, or the sort who always finds a way?

The answers are straightforward. That’s the power of changing your questions from “what” to “why.” It doesn’t eliminate every hard choice, of course. But it really helps dispel the weird inertia that keeps us from doing good things.

Step back and view the full sweep of your biography. Do you want to be the kind of person who brushes his or her teeth, who prays or meditates often, who calls his relatives frequently, who is generous and patient and kind? Plenty of times, you won’t feel like acting that way in each individual moment. But that’s okay. Because you’ve stopped asking, “What do I feel like doing?” and you’ve started asking ,“Who do I aspire to be?” instead.

That’s the escape rope from the tyranny of small decisions. Stop acting. Start being.

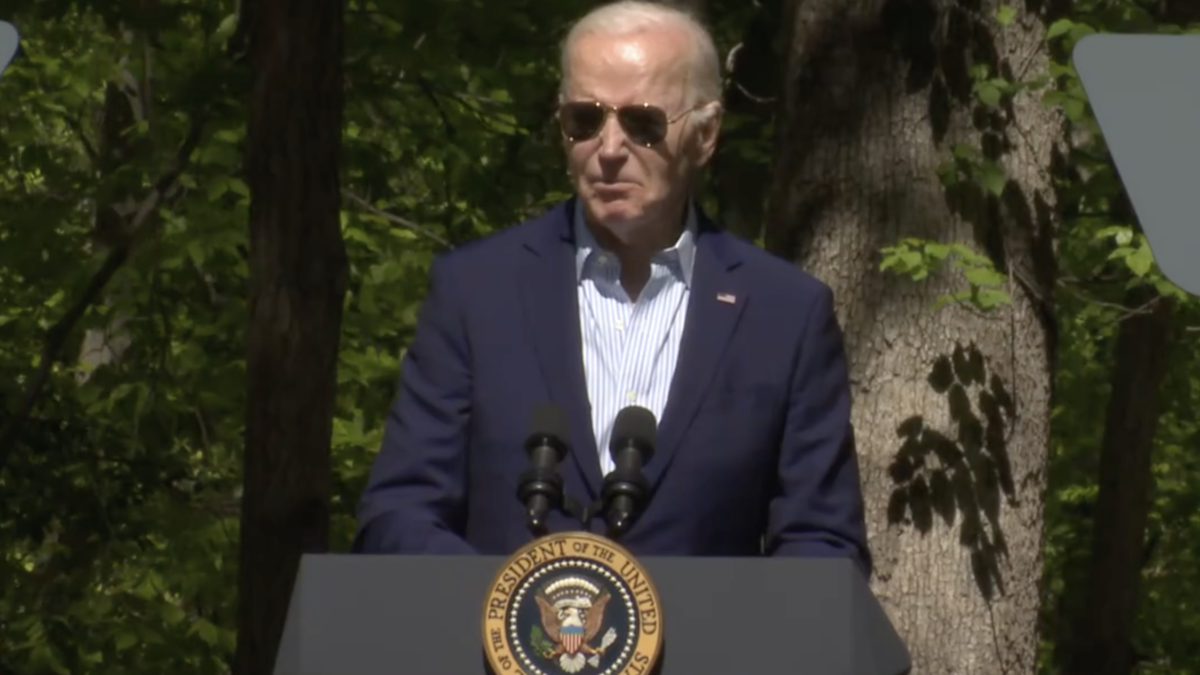

Neither your character nor our country should be the accidental byproduct of a thousand shortsighted decisions. Carve out time to think deliberately about the character you hope to cultivate. Let those principles flow down into daily decisions. And the next time you hear two politicians debating, make sure to zoom out of the pseudo-pragmatic policy particulars and ask, “Which guy’s America do I want my grandkids to live in?”

These practices will help you stick to that nifty “life hack.” If we’re lucky, they might also help us transform our government.