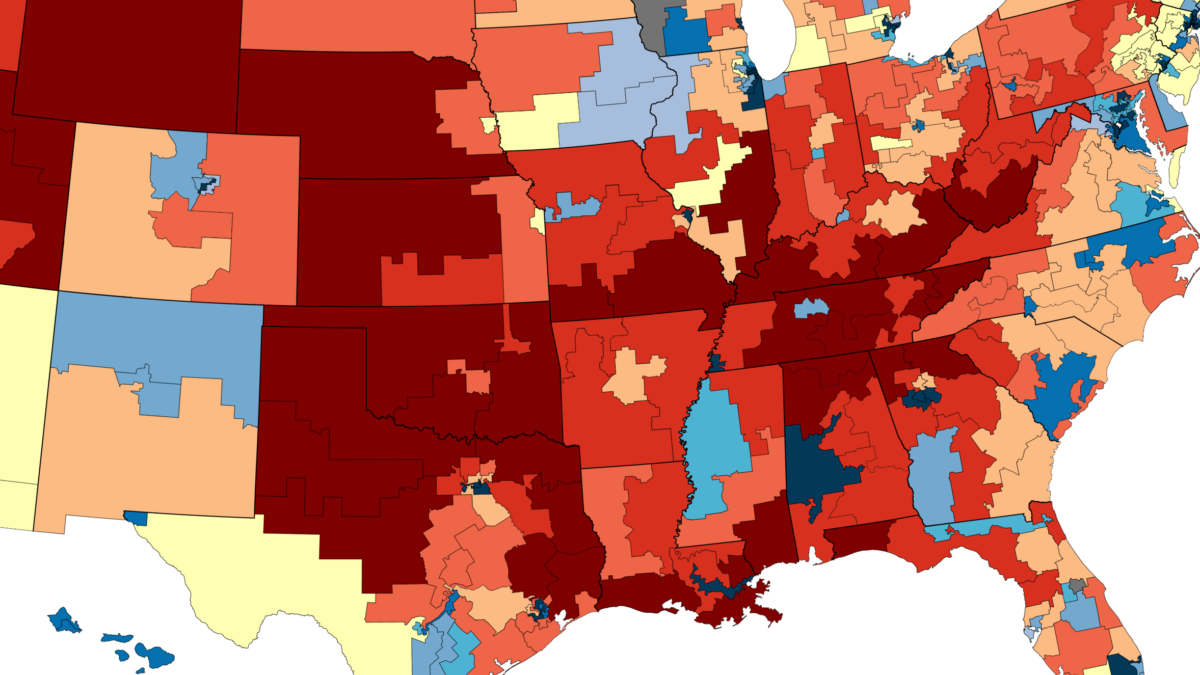

The U.S. Supreme Court heard arguments last month in a case from Alabama called Merrill v. Milligan. Most people have not heard of it, but it has the potential to be the most consequential case on the redistricting requirements of the Voting Rights Act (VRA) in a decade. The court has long wrestled with and sought to clarify the VRA requirements, in the past 20 years especially, yet rulings have only further confused the issue.

Legislators and map drawers have an impossible task. They must use racial considerations (i.e. the percentage of the population that is a minority group) to draw districts when the Voting Rights Act requires it, but if they draw districts based on race when the Voting Rights Act does not require it, then they risk racially gerrymandering in violation of the 14th Amendment’s equal protection clause. That clause has been understood to protect the rights of all Americans regardless of their race or ethnicity.

Shortly after the VRA became law in 1965, the Supreme Court began contemplating what exactly it required in redistricting. It took until 1986 for the court to settle on a set of parameters mapmakers should use under what is known as Section 2 of the VRA. The opinion, in a case called Thornburg v. Gingles, ordered that majority-minority districts were required by the VRA if districts could be drawn that were reasonable, compact, and contain a sufficiently large minority population that votes as a group. The Gingles elements seemed reasonable 36 years ago, but not a single factor has a clear standard today.

Subjective Standards

The problem with a reasonableness standard is self-evident. Whether a district is “reasonably configured” is an inherently subjective determination. A reasonably configured district to one judge could easily be seen as unreasonably configured to another.

The compactness requirement received the most attention during the Merrill arguments. Justices Samuel Alito, Brett Kavanaugh, and Amy Coney Barrett appeared to recognize that the many different ways one can conceptualize “compactness” makes compliance difficult to measure and seemed skeptical Alabama’s congressional map was illegal. Justices Elena Kagan, Sonia Sotomayor, and Ketanji Brown Jackson strongly indicated their view that the plaintiffs met the “compactness” requirement and Alabama’s map should be replaced. This lack of agreement isn’t surprising, since the court has not set a clear, objective rule for what constitutes a compact district.

Finally, the court said in a 2019 case, Rucho v. Common Cause, that federal courts should not hear partisan gerrymandering lawsuits because the courts are not well-suited to consider the political questions these cases require. It stands to reason that the federal courts may also be ill-equipped to consider the complex political analyses necessary to determine whether a minority population votes sufficiently as a group to satisfy the Gingles criteria.

Two Options for Clarity

The court has two real options to provide clarity to this muddled area of law and also resolve Merrill: Either establish a bright-line rule governing this type of VRA redistricting challenges or hold that the VRA does not apply to redistricting. Absent that level of clarity, the court will continue to invite a deluge of this kind of VRA litigation.

The first option is a straightforward rule that clearly defines the scope and application of the Gingles requirements. This could include requiring plaintiffs to show a minority population of a single race is sufficiently large and geographically compact to comprise a majority in a potential single-member district. Such a rule, with clear guidelines, could give lower court judges a clear standard to apply and reduce the number of aggressive, borderline frivolous claims brought in recent years.

A second option is for the court to decide that this section of the VRA does not apply to the redistricting context and remove the courts completely from these battles. This position would bring about the end of what Chief Justice John Roberts once called the “sordid business” of “divvying [Americans] up by race” and a set of rulings whose underlying assumptions Justice Clarence Thomas criticized as “repugnant to any nation that strives for the ideal of a color blind Constitution.”

Much of the court’s struggles may be a natural result of the ongoing political realignments and demographic changes in America. As our communities and families become more multiethnic, and our politics less siloed, the more fraught considerations of race will be. The standards of four decades ago do not align with a country that has changed significantly since.

Absent a clear ruling from the Supreme Court, VRA compliance will only get more difficult, and an ever-expanding torrent of litigation will follow. The court should take this opportunity to bring clarity or closure to decades of seemingly contradictory law.