Chick-fil-A, that alluring purveyor of delicious chicken sandwiches and waffle fries, has long been a target in certain quarters. These criticisms have nothing to do with the addictiveness of the chain’s food (a shame, really, because this is a real problem), but its perceived political stances. Most such attacks have stemmed from the chain’s indirect donations to groups that oppose same-sex marriage, and from CEO Dan Cathy’s comments on the subject.

Conservatives are certainly no strangers to boycott campaigns, and consumers have every right to register their values through market activity. Indeed, shortly after this blowup, Chick-fil-A largely stopped making such donations. You’d be forgiven for thinking the storm had passed.

That makes this recent New Yorker article by Dan Piepenbring—memorably entitled “Chick-fil-A’s Creepy Infiltration of New York City”—all the more incoherent. According to Piepenbring’s screed, which lacks content beyond Ewww-These-People-Aren’t-Like-Me, Chick-fil-A’s arrival in the Big Apple “raises questions about what we expect from our fast food, and to what extent a corporation can join a community.” Evidently, Piepenbring can’t understand why the restaurant is so popular with NYC residents, given the city’s progressive political and social leanings. How can this be?

Why People Keep Buying Chick-fil-A

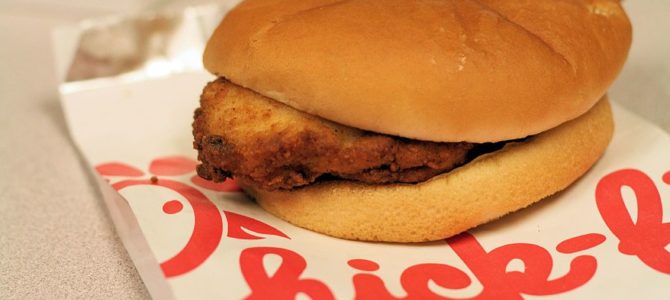

Since he’s having trouble grasping this, I’ll help him out. First of all, Chick-fil-A food is delicious, as anyone who’s ever tasted an Original Chicken Sandwich or a Chicken Biscuit well knows. Second, Chick-fil-A is beneficial to communities because it treats its workers well and screens its franchisees rigorously, ensuring a high standard of quality across all the chain’s restaurants.

Third, Chick-fil-A is a pleasant environment because its employees are friendly and respectful and its facilities are spotless. Also, for what it’s worth, when pressed about perceived “anti-LGBT” stances, the restaurant focused its donations elsewhere. So, by any sensible standard, Chick-fil-A should be a model company for any progressive interested in workers’ rights and community reinvestment. What more could Chick-fil-A do to be one of the “good guys”?

But Piepenbring is having none of it. In perhaps the article’s most ludicrous segment, he criticizes Chick-fil-A’s cow-driven advertising campaigns by “asking why Americans fell in love with an ad in which one farm animal begs us to kill another in its place. Most restaurants take pains to distance themselves from the brutalities of the slaughterhouse; Chick-fil-A invites us to go along with the Cows’ Schadenfreude.”

Two can play at this game, Dan. The fast-food world is indeed full of problematic content: Burger King reinforces norms of patriarchy and feudalism, Wendy’s teaches that a woman’s place really ought to be in the kitchen, Arby’s denigrates veganism and celebrates animal slaughter, and Taco Bell’s chihuahuas perpetuate harmful stereotypes. (I could go on.)

Surely There Aren’t Christians in Manhattan!

The rest of Piepenbring’s “argument” fares no better, although it’s certainly an illuminating look at its author’s unjustified neuroses. He writes that “the brand’s arrival here feels like an infiltration, in no small part because of its pervasive Christian traditionalism. Its headquarters, in Atlanta, is adorned with Bible verses and a statue of Jesus washing a disciple’s feet.” It must surprise the Christians of New York (or, for that matter, to erstwhile residents of the American South) that they are “infiltrators” in their own community. But in Piepenbring’s world, any outsiders must be shunned.

Not content with the language of “infiltration,” Piepenbring further claims “there’s something especially distasteful about Chick-fil-A, which has sought to portray itself as better than other fast food: cleaner, gentler, and more ethical, with its poultry slightly healthier than the mystery meat of burgers. Its politics, its décor, and its commercial-evangelical messaging are inflected with this suburban piety.” Elsewhere, he’s scandalized by the fact that “[t]he restaurant’s corporate purpose still begins with the words ‘to glorify God,’ and that proselytism thrums below the surface of the Fulton Street restaurant, which has the ersatz homespun ambiance of a megachurch.”

Contempt drips from every word of these sentences. None of this amounts to a substantive criticism of the restaurant’s treatment of animals, labor practices, products’ nutritional value, or anything else. It’s merely Piepenbring’s bleating admission that he cannot handle anything reminiscent of the great bugbear of our time: American evangelicalism.

I think this a staggeringly overused accusation and thus rarely use it, but Piepenbring’s article reflects flat-out bigotry—that is, “stubborn and complete intolerance of any creed, belief, or opinion that differs from one’s own.” Judging by the tenor of his article, his decisive pronouncement—“Chick-fil-A, too, does not quite belong here. Its arrival in the city augurs worse than a load of manure on the F train.”—has nothing to do with Chick-fil-A’s actual behavior, and everything to do with the chain’s perceived religiosity.

In other words: get out of town, you religious yokels, and stop doing such a good job selling chicken. For sheer self-righteous toxicity, this take is hard to beat.

Guys, Your Smug Is Showing

Beyond the glaring deficiencies of Piepenbring’s piece, the appearance of this article in The New Yorker tends to corroborate a particular criticism frequently raised against “elite culture”: it often reflects a smugly unwavering belief in their moral superiority.

It has become de rigueur among progressive writers charged with this “smugness” to allege they’re simply stating facts, that we can’t normalize the status quo, that their ideological opponents are really just that stupid. What’s perceived as smug, the argument runs, is simply the truth, and that’s the end of it. The alleged problem of smugness is just a smokescreen.

Well, for those still curious, this is exactly what smug looks like.

When all’s said and done, though, if Piepenbring wants to run in terror from the Chick-fil-A juggernaut, maybe that’s all right. Let him have his Ben and Jerry’s. It just means more chicken sandwiches for me.