“Winslow Homer: Crosscurrents” opens at The Metropolitan Museum of Art this month. The exhibit is one of those instances in which the critic must opine on a superb collection of art that is presented in a subpar fashion.

Fortunately for you, gentle reader, the art is so very, very good that it remains the focus of both the exhibition and this critique of it, even if we may sail into some choppy waters before putting in to shore.

The work of Winslow Homer (1836-1910) appeals to many different kinds of people, for reasons as diverse as the kinds of art he produced during his long career. Some admire the painterly abstractions of his seascapes along the coast of Maine. Others are drawn to his images of the people who populated rural America.

Outdoor types in particular love his dynamic depictions of animals such as birds, fish, deer, and the pursuit thereof. This highly varied output is all the more remarkable given that Homer was largely, albeit not entirely, a self-taught artist.

A Broad View of Winslow Homer’s Work

There hasn’t been a large show of Homer’s work at a major American museum since the National Gallery of Art’s massive retrospective back in 1995. While The Met’s new exhibition isn’t quite as large, it does contain 88 paintings from The Met’s extensive collection, along with significant loans from close to 50 other institutions and private collections.

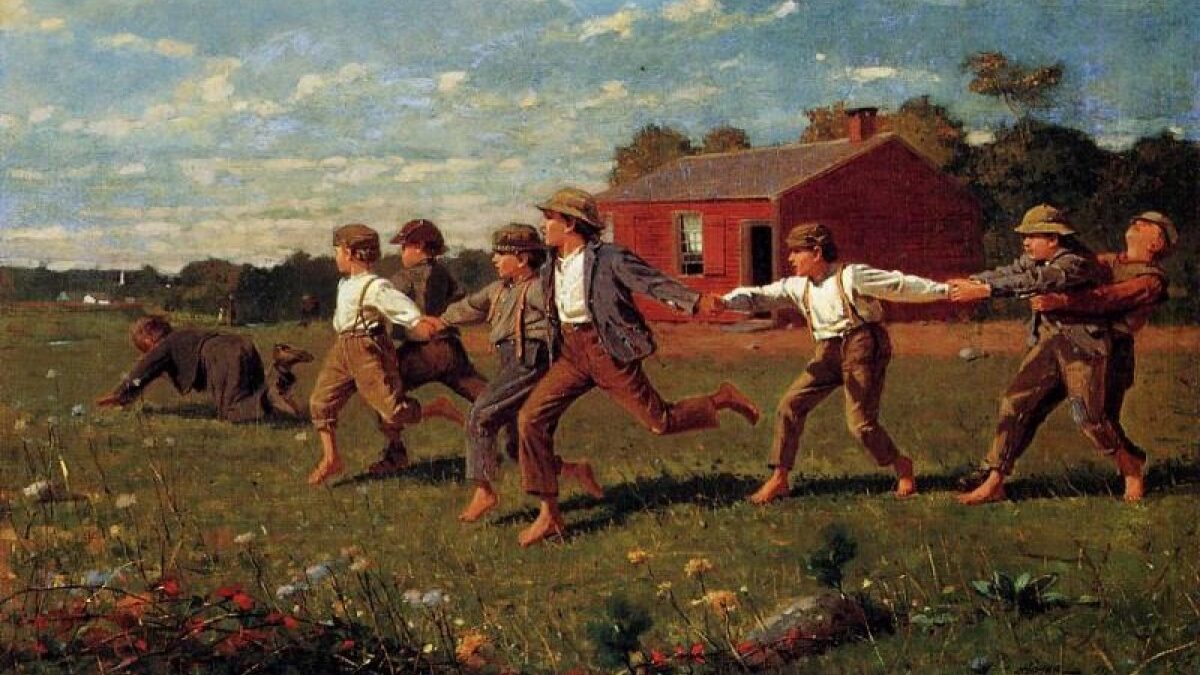

Thus, it has the feel of a retrospective. As one might expect, many popular favorites are here, such as “Breezing Up (A Fair Wind)” (1873-76), “Snap the Whip” (1872), and others. In addition, there are also a number of works that will be unfamiliar to many visitors.

Themes of conflict, compassion, nature, survival, and death run through much of Homer’s work, and it is in these areas that the exhibition takes a particular interest. Fortunately, there are plenty of moments of respite, where one can enjoy simple pleasures such as a wonderfully observed branch of orange fruits and blossoms.

As laid out during the exhibition preview by The Met’s Director Max Hollein, Homer’s “deeply humanist” art often shows “the tension between sentiment and struggle,” and the museum clearly has a keen interest in introducing Homer to a new generation. As with all great art, I would argue that Homer remains as relevant to today’s audiences as he was to his own time without the need for a contemporary gloss, but there you are.

The Focal Point of the Show

Entering the exhibition, one is confronted by an eye-catching architectural cutout. It draws the gaze through the opposite wall into another gallery behind it, focusing attention on The Met’s painting “The Gulf Stream” (1899), which serves as the focal point of the show. Indeed, this was the first Homer painting The Met purchased for its permanent collection, back in 1906.

“The Gulf Stream.” Wikiart.

This piece neatly encapsulates a number of the thematic elements Homer revisited again and again. We witness a man in a decrepit fishing boat struggling against both a violent, churning sea and the threat of attack by a shiver of hungry sharks. Appropriately enough, like the eye of a hurricane or the center of a whirlpool, the installation swirls counterclockwise around this piece, so that by the end of the visit one has made a 360-degree circuit back to the start.

Progressing from gallery to gallery, the subjects and styles change as Homer’s art itself changed. We begin with his scenes of the Civil War and Reconstruction, including the quiet power of “Prisoners from the Front” (1866), and the monumental yet softly, gorgeously lit image of “The Cotton Pickers” (1876), showing influences from contemporary French painters such as Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot (1796-1875) and Jean-François Millet (1814-1875), along with Homer’s popular, nostalgic images of rural American life.

We then move through his exploration of the human struggle to the frigid, tumbling waters of the North Atlantic, particularly as related to the two years Homer spent living in a small coastal village in northern England before returning home to settle in Maine. We get a bit of a respite with a number of Caribbean scenes, although even here as with “The Gulf Stream” and “After the Hurricane” (1899), the threat posed by nature is never entirely absent.

Toward the end of Homer’s life, we move into darker territory once again, but now human beings are often absent. Crashing seas and dark skies are interrupted only by the presence of animal life, which is shown trying to survive in harsh circumstances.

An American Masterpiece

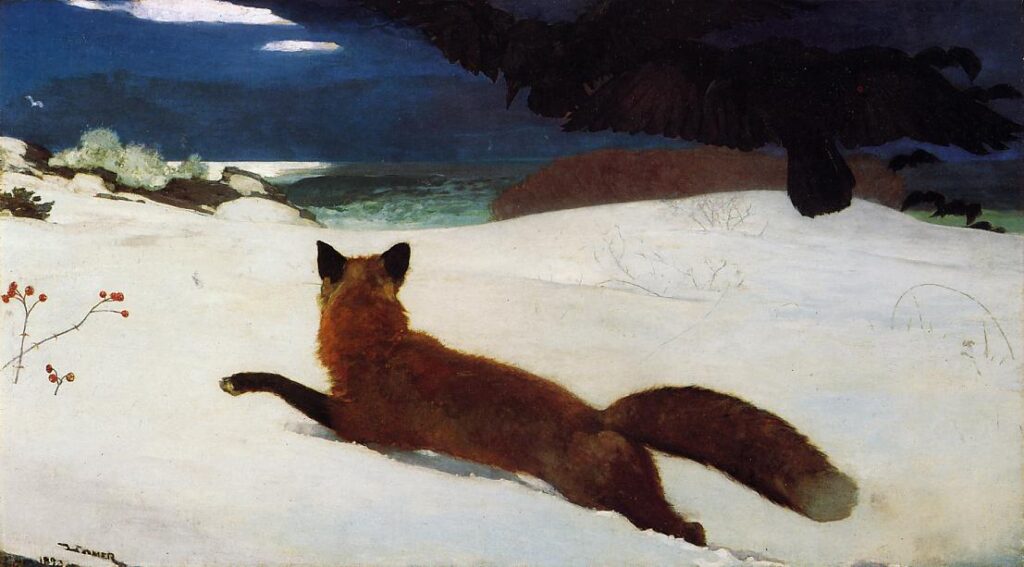

To that point, before taking a look at everything else in the exhibition I zoomed through the circuitous installation to see whether one of Homer’s later paintings, and my personal favorite of his work, was in the show. And so it is.

“The Fox Hunt” (1893), on loan from the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, is appropriately displayed in almost majestic isolation at the conclusion of the exhibition. Not to put too fine a point on it, but this is surely one of the greatest masterpieces of 19th-century American art.

Notice the placement of the red fox on a diagonal path across the white foreground, and the incoming threat of black crows on an intersecting diagonal from the upper right, all set against the inhospitable landscape of coastal Maine in deep winter. There’s a tremendous amount of drama in this picture, and Homer intentionally leaves the viewer hanging, wondering what happened next.

I always like to think that the fox’s apparent glance toward the sea suggests he managed to get away from his attackers, but one could certainly have an interesting discussion on this point. The painting is a testament not only to Homer’s skills in composition, handling, and technique but also to his ability to tell an engaging story using only a single image.

The Setting a Contrast to the Work

Pictures such as this are what make the quieter, slower pace of life as observed by Homer at other points in his career seem like they were created in another universe or by a different individual. Yet whether we are looking at children on a hillside or a moonlit seascape, there’s a consistent liveliness in how Homer translates what he observes into two-dimensional form. It seems particularly odd, then, that the exhibition where these works are displayed should prove to be such a sterile, lifeless affair.

Perhaps one might make the charitable observation that the pale gray walls of the installation enhance the highlighted elements of a handful of the pictures, such as “Right and Left” (1909). Yet when combined with the aforementioned architectural cut-outs, the unusually wide spacing between many of the objects, and the vast gallery spaces that stretch high up to acoustic tile drop ceilings dotted with track lights, the overall effect is rather clinical. One gets the feeling of slogging through miles of hospital corridors lined with pictures available for purchase through the gift shop in the lobby, along with helium balloons and potted plants.

Far more disturbingly, while the placards in the show are generally helpful and informative, the exhibition catalog is, in places, an eye-rolling concoction of artspeak peppered with the kind of purple prose one expects to read in a course outline at Oberlin. If this is meant to attract a new generation of viewers to one of America’s best artists, it does so by consciously alienating a host of potential visitors who do not attend art exhibitions to be preached at. The Walters Art Museum understood and handled this in a far superior fashion in its current “Majolica Mania” exhibition. I prefer to entertain the condescension of the cognoscenti, when I prefer it at all, in 280 characters or fewer.

There’s much to admire, learn about, and simply enjoy in this new offering at The Met. If you happen to find yourself in New York this spring or summer, you should definitely make the time to see this show. With the high costs involved in exhibitions of this size due to the art lending process, it’s difficult to imagine when such a comprehensive collection of Homer’s work might be gathered again all in one place.

If you do go, please go to look at the art, and simply enjoy it for what it is. As is often the case in our cultural institutions of late, those who are desperate to try to prove their continued relevance by shoehorning something from another age into parameters defined by current academic and popular theories will, in time, prove to be just as dated an approach to understanding the art as the earlier views it seeks to supplant.

“Winslow Homer: Crosscurrents” is at The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York from April 11 to July 31, 2022, before traveling to the National Gallery in London in a slightly different incarnation in the autumn. For tickets and more information, please visit here.