If the subtitle of “Dollhouse: The Eradication of Female Subjectivity from American Pop Culture” says anything about the new animated film, it is that it’s anything but subtle. The mockumentary follows the rise and fall of a fictional child pop sensation, Junie Spoons, through interviews with everyone who was part of her life. Nicole Brending wrote, directed, voice acted, edited, designed the dolls, handled the cinematography, and cowrote the score, maintaining a clear if unchecked vision throughout.

As a satire, the film goes to extremes to tell its story. While it’s the point of the film to exaggerate real-world situations to comment on misogyny, the cynicism and unpleasantness that permeates the film overshadows the humor and message. Most situations are taken well past extreme.

It can be very hard to watch at times, not due to an outpouring of emotion or empathy, but due to sheer discomfort. Rather than support Brending’s intended message, many of these moments undercut by way of distraction.

When it takes a more nuanced approach, the film can be extraordinarily funny, moving, and clever. There are some truly spectacular moments that use more subtle means to make their points. The characters are interesting and fun when allowed to behave like human beings and not caricatures, with specific designs and personalities.

Nowhere in the film was the subtle humor better demonstrated than in the music. Junie Spoons’s songs and music videos highlighted her character progression, as well as shifting trends in pop, with a grace and intelligence I wish permeated into more of the film.

The songs, written by Jean-Olivier Bégin and Brending, sound impressively similar to the pop music that my friends and I enjoyed in primary school and junior high, with bouncy, catchy tunes and shockingly sexual lyrics hidden beneath the thinnest of metaphors. Maggie Morrison, who sang as Junie, has a beautiful voice well-suited for the movie’s pop style.

Despite not being a big fan of pop, I found myself genuinely looking forward to the songs. They walked a beautiful line between parodying the absurdity of hyper-sexual teen pop and believably fitting in as an entry into the genre.

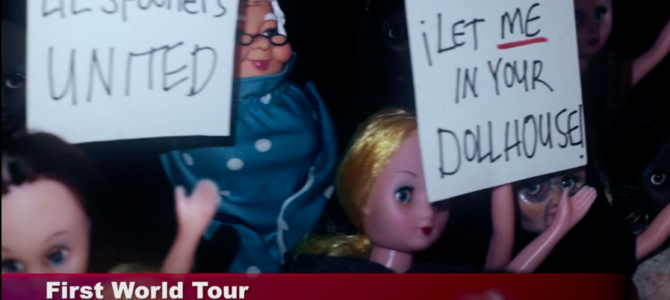

Rather than use traditional animation, the characters were presented by specially designed, Barbie-like dolls with static faces and minimal physical movement. The dolls were thematically interesting, as they highlighted the protagonists’ complete lack of agency. It’s a little on the nose, but the quick storytelling shorthand allows more time for the many other ideas to be explored.

The dolls also serve a practical function: much of the action takes place while the protagonist is underage, including many sexual situations. Dolls save the team from having to find an actress who could believably pass for 12 years old. Further, audiences can handle far more grotesque and uncomfortable situations in animation than with live actors. The film goes to some dark places, and the animation keeps it from becoming even more unpalatable.

By using dolls rather than other forms of animation, the film loses the ability to tell certain parts of the story through visual cues from the characters. There is minimal physical movement, which limits body language, and no changes in facial expressions. In normal animated or live-action film, so much is communicated by the facial expressions and body language, so that element is lost.

Luckily, the voice acting helps to mend the gap. Every character in the large ensemble is voiced by one of five actors: Brending, Sydney Bonar, Aneikit Bonnel, Erik Hoover, and Peter Ooley. Each of the voice actors injected life into their characters, and their energy and personalities saved the film from becoming lifeless.

The doll designs are spectacular. Brending did an incredible job creating specific looks for each character, which tell you a lot about who they are in one frame. With the sizable number of characters, it’s an impressive feat to make each one feel unique. Brending likewise voiced half of the characters, which was nearly undetectable until the end.

Indelibly linked to the film is its message. The film is meant as an indictment of misogyny in all forms, and tries to tackle as much as the two-hour runtime allows. The ambition is laudable, but the film gets over-crowded. Once a subject begins to be explored in an interesting manner, the film pivots hard to its next topic. By attempting to cover too much, “Dollhouse” ultimately says very little.

Had fewer aspects of feminism been addressed, the script could have gone deeper. As it stands, the film feels more like distinct episodes strung together by the same characters and general themes. Not every movie needs to have one overarching plot, and many handle meandering stories beautifully, but a stronger through-line would have been appreciated, to give the story some direction. It can be a bit dizzying how quickly the plot jumps around.

For all its faults, “Dollhouse” has one of the best endings I’ve seen in a while. The third act goes rather off the rails with several bizarre and seemingly out-of-place segments, but it is saved by the absolute punch to the gut that is the final few minutes. Without giving anything away, the ending takes the film to an incredibly dark place though a deftly executed twist.

However, unlike the rest of the film’s bleaker moments, this one is handled perfectly. The tone and the action are ideally matched, leaving audiences simultaneously disturbed and surprised. The best types of twists are the ones you don’t quite see coming, but in retrospect are the only logical conclusion for the story, and “Dollhouse” found that balance.

The shallowness of the satire and disconcerting imagery bog down what could have been a perfectly fun or interesting film. Brending’s beautiful visual style and ability to craft engaging characters are on full display, but the film’s attempt to say everything about misogyny leaves only a cursory understanding of the myriad topics addressed.