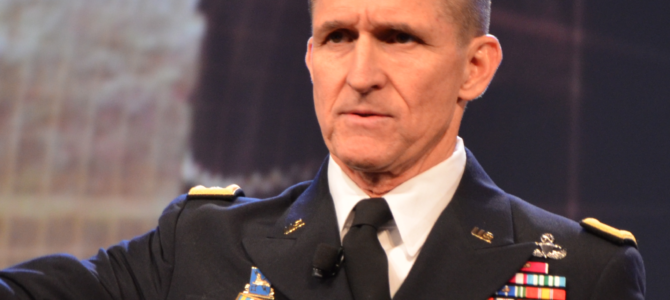

Retired Lt. Gen. Michael Flynn faces the real possibility of jail time when he is sentenced at the end of this month in connection with the guilty plea he entered in 2017. But that plea appears to be tainted because his original lawyers had a conflict of interest that arose from their involvement in one of the offenses folded into the plea. The fallout from that conflict of interest appears to have created Flynn’s current predicament.

Robert Mueller’s Office of Special Counsel investigated Flynn for potential criminal charges that included 1) lying to the FBI about his conversation with the Russian ambassador while he was part of President Donald Trump’s national security transition team, and 2) making a false statement in his filings under the Foreign Agents Registration Act (FARA) for work he had allegedly done for the government of Turkey prior to the Nov. 8, 2016, election.

Covington and Burling, LLP, a prominent law firm, represented Flynn in the investigation and in plea negotiations. The firm also assisted him in preparing the allegedly false FARA filings.

The Nature of FARA Filings

FARA is a complex law, and people who must make filings under it often seek the assistance of counsel, just as taxpayers who must file a complicated tax return also seek professional assistance. If the government subsequently asserts the FARA filing (or the tax return) is criminally false, the attorney is potentially implicated along with the client.

The lawyer’s interest in defending his or her actions may conflict with the obligation to zealously defend the client. Furthermore, the attorney can be a key witness if the client is charged, which may also disqualify the lawyer from representing the client in the criminal case.

In Flynn’s case, the Covington lawyers would have been witnesses either for or against Flynn regarding his FARA filings and any related potential criminal charge brought against him. Flynn was entitled to rely on Covington’s advice so long as he dealt honestly with the firm and did not deliberately withhold relevant information. This would give him a “good faith” defense to any charge that the filings were false.

Thus, the Covington attorneys who helped Flynn prepare his filings could become the star defense witnesses if they said any mistake in the filings was their responsibility rather than Flynn’s. In that event, no conflict would arise between Flynn’s interest and Covington’s interest.

On the other hand, if Flynn provided incorrect information to Covington that was included in the FARA filings, a clear conflict emerges because Covington has an interest in absolving itself from any responsibility and placing the blame entirely on Flynn. If Flynn had deliberately provided false information to Covington, the Covington attorneys would become witnesses against Flynn, and no lawyer at the Covington firm could represent Flynn with respect to the FARA charge.

If, instead, Flynn innocently provided incorrect or incomplete information to Covington, the situation becomes muddier. While the Covington attorneys would still implicate Flynn as the source of the incorrect information in the FARA filings, they might be able to temper this with testimony about the surrounding circumstances that indicated Flynn had acted in good faith despite inaccuracies. But because Covington would still have a strong interest in ensuring the firm appeared blameless, there would still be a conflict between its interests and Flynn’s.

Did Flynn Know He Was Providing False Information?

Flynn’s current counsel says this last scenario is what actually happened, that Flynn innocently provided incorrect information to Covington. It is certainly implausible that Flynn would hire a reputable firm like Covington and pay it a six-figure fee to prepare FARA filings on his behalf, only to deliberately provide the attorneys false information for inclusion in those filings. Nonetheless, the government alleged this is exactly what Flynn did.

Notwithstanding the potential conflict of interest between it and Flynn, Covington represented Flynn in his plea negotiations with the government and struck an agreement whereby Flynn effectively admitted to both lying to the FBI and making a false statement in his FARA filings.

Technically, Flynn pleaded guilty to only one count of making a false statement to the FBI; he did not plead guilty to making false statements in his FARA filings. The written Statement of Offense submitted to the court as part of Flynn’s plea, however, includes facts relating to both offenses. The government inserts facts about other offenses in a Statement of Offense when it wants to establish that those facts are “relevant conduct,” which the court then considers along with the offense of conviction in imposing a sentence.

Flynn now disputes whether he admitted in the Statement of Offense that he knew at the time he provided the FARA information to Covington that it was false. He says he only learned so later. To constitute a criminal false statement, the information must be false, and the defendant must know so at the time he makes the statement. If a person makes an incorrect statement he or she then believes to be true, no offense has been committed.

Covington Had a Conflict of Interest

Covington lawyers certainly would have known the law required this element and would have realized the government would consider the Statement of Offense to be Flynn’s admission that he made a false statement in the FARA filings. This means Covington had a conflict of interest.

Flynn’s plea was implicitly an admission that he lied to Covington in creating the FARA filings. This conflict should have precluded Covington from representing Flynn in entering this guilty plea as it is structured, with the FARA filings being a part of the criminal conduct for which Flynn will be sentenced.

Apparently, the government raised with Covington the possibility that it might have a conflict with Flynn due to its role in the FARA filings. Covington allegedly assured the government that it had discussed the potential conflict with Flynn and that he wanted the firm to continue representing him. In other words, the firm says he “waived” the conflict.

Prosecutors have a stake in conflict issues between defendants and their lawyers because a plea entered by a defendant whose counsel has a conflict of interest is vulnerable to being overturned. Thus, the government often requires that the defendant provide a written waiver of any conflict with defense counsel before it proceeds with a plea agreement.

In this case, however, the government did not do so. Nor was the conflict brought to the court’s attention when the plea was entered, nor addressed in any way in the plea papers. If Flynn had actually pleaded guilty to the FARA charge, instead of simply including the FARA conduct in the Statement of Offense, the conflict of interest issue likely would have surfaced during the plea proceedings.

Flynn Hires New Counsel

Flynn was originally scheduled to be sentenced in December 2018, but that proceeding fell apart after the court raised several issues. First, the judge questioned Covington’s claims in its sentencing memorandum that the FBI had improperly conducted its interview of Flynn.

Second, because Flynn had not yet completed his cooperation with the government pursuant to his plea agreement, the judge questioned whether Flynn wanted to complete his cooperation to get full credit for it on his sentence. Specifically, Flynn had not yet testified in federal court in Virginia against his former business partner, who was scheduled to be tried in summer 2019 on non-FARA charges relating to their firm’s work, allegedly performed for the government of Turkey.

Flynn decided to postpone his sentencing, and in June 2019, he hired new counsel to replace Covington. His new counsel, led by Sidney Powell, asserted that Flynn had not willfully and knowingly made false statements in the FARA filings because he did not believe the filings were false when he submitted the information to Covington.

Although this is an essential element of a false statement charge, the language of Flynn’s Statement of Offense is not crystal clear on this point. Rather, it uses standard legal jargon that an experienced lawyer or judge would understand to encompass this element, but that a lay person probably would not, unless the counsel advising him in the plea process had explained it to him. Because Flynn said he did not know the FARA filings were false at the time they were submitted, he was dropped as a government witness in the Virginia case. The court ultimately acquitted the business partner.

Flynn’s new counsel also asked the court to dismiss his case for alleged government misconduct in investigating Flynn and in allegedly failing to turn over exculpatory materials in his case. In doing so, she raised arguments of innocence on Flynn’s behalf, notwithstanding his guilty plea. The court rejected those claims and set the case for sentencing on Jan. 28, 2020.

The Government Flip-Flops on Sentencing

Last week, the government filed a memorandum changing its position about the sentence Flynn should receive. In 2018, the government said a non-jail sentence was appropriate for Flynn, considering his military service, his acceptance of responsibility for his criminal conduct, and his cooperation in the case against his former partner.

The government now argues that Flynn reneged on his agreement to cooperate in the Virginia case, has reversed course on accepting his criminal responsibility for the FARA filings, and thus his sentence should not be mitigated. Accordingly, it seeks a jail sentence of up to six months’ imprisonment for Flynn. In making this argument, the government relies heavily on Flynn’s plea agreement and his Statement of Offense.

Flynn is now experiencing the unpleasant effects of his conflict of interest with Covington and his misinterpretation of what he was admitting to in his guilty plea. The government now wants the court to question Flynn, before he is sentenced, about his claims of innocence and his misunderstanding of the FARA issue.

In a highly unusual request by the government, it seeks to force Flynn to disavow those claims or else lose any sentencing credit for cooperation and accepting responsibility. Defendants have a Fifth Amendment right to be silent even at a sentencing proceeding and cannot be compelled to answer such questions. The government requesting that the court quiz Flynn to disavow positions his current counsel is raising on his behalf is extraordinary.

Such an unusual request speaks to how the government appears to believe that the fault for the tangled sentencing situation lies entirely with Flynn and that, having “repented” his plea, he is now playing fast and loose with the truth before the court. But another distinct — and more likely — possibility is that Covington, hindered by its own conflict of interest, was not as zealous an advocate as it should have been in resisting the FARA charge and was not as clear with its client as it should have been in explaining the consequences of his guilty plea, including the FARA issue in the Statement of Offense.

Flynn Shouldn’t Be Punished for Others’ Errors

Indeed, given the conflict of interest in this case, most white-collar attorneys in Covington’s position would not have undertaken Flynn’s representation at all, or would have withdrawn once it became apparent the government was insisting on having the FARA issue be a part of any plea agreement. This is also why any purported “waiver” by Flynn of the conflict is invalid.

The Rules of Professional Responsibility require that the lawyer first have a reasonable belief that he can zealously represent the client, even with the conflict, before the client can seek a waiver. It is impossible to see how a lawyer could reasonably conclude, on these facts, that Covington could represent Flynn in the plea.

Last night, after hours, Flynn’s counsel filed a new motion — to withdraw Flynn’s plea — saying the government breached the plea agreement. Powell states plainly that she believes Covington had a conflict in its representation of Flynn. She suggests the conflict led to the impasse between Flynn and the government over his testimony in the Virginia case.

It is clear that while these issues should have been squarely addressed long before now, if there is to be a just result in Flynn’s case, the court must take up the question about a conflict of interest by Covington in Flynn’s plea. This case has already lingered on the docket far longer than most plea-resolved cases, and it’s time to wrap it up. Nevertheless, Flynn should not be punished for mistakes that are attributable to his counsel rather than to him.