We regularly witness the increasingly aggressive and activist posture of our nation’s judiciary. The issue recently came to a head with Judge James Robart’s extra-constitutional act of staying a significant portion of the president of the United States’ foreign policy initiative and the subsequent affirmation of that stay by the unabashedly activist Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals.

Those of us who value the restrictions the Constitution places on government cannot help but worry over the implications of these unprecedented confrontational actions and the effects they will have upon our republic. Indeed, we are left with the troubling question of whether there is any solution to this latest assault upon the fabric of our Constitution. But perhaps there is.

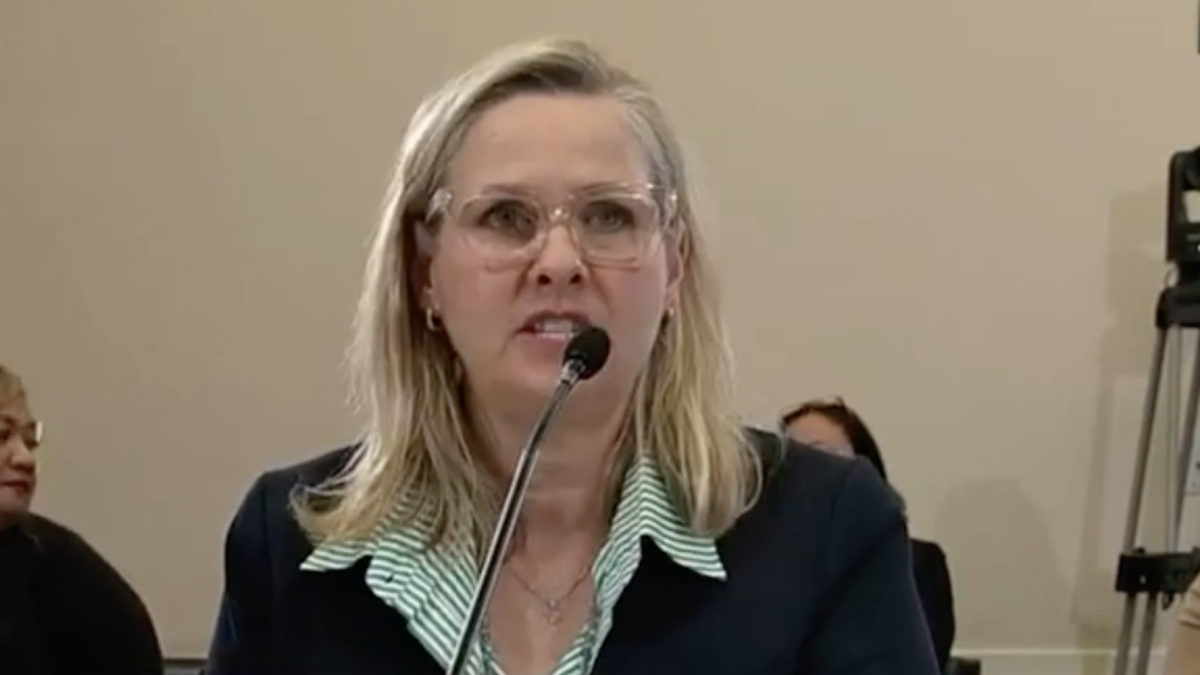

In January, I filed a bill in the Florida House of Representatives that proposes a legislative override provision to Florida’s Constitution. I also filed an accompanying memorial suggesting that Congress consider a similar addition to the United States Constitution.

American Judicial History Lends Support to This Idea

To see why such a provision would be necessary, a review of our nation’s constitutional history regarding the judiciary is warranted.

Article III of the U.S. Constitution gave the courts “Judicial Power” over all cases and controversies arising out of the laws of the United States and the Constitution, but it did not assign to the Supreme Court final (plenary) authority regarding the constitutionality of laws. The Supreme Court actually seized this power in its seminal Marbury v. Madison decision of 1803. In it, Chief Justice John Marshall singlehandedly declared, “It is emphatically the province and duty of the judicial department to say what the law is.” Consequently, any law the court determines is repugnant to the Constitution will be void.

Although the Congress of the day did not react to this, by 1820, the consequences of the resulting change in the relationship between the three branches of government caught the attention of Thomas Jefferson, who warned in a letter to Jarvis Williams, “to consider the judges as the ultimate arbiters of all constitutional questions [would be] a very dangerous doctrine indeed, and one which would place us under the despotism of an oligarchy.”

The Civil War and its associated amendments set the stage for the fulfillment of Jefferson’s prognostications. The Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution included Due Process and Equal Protection clauses that federal judges would subsequently employ to force their will and power upon the states. With the appointment of progressive judges during the twentieth century, the Supreme Court engaged in the laborious work of redefining the various passages of the Constitution in manners neither foreseen nor intended by the Framers.

The Court Seized the Power to Redefine the Constitution

With their new powers, the Supreme Court applied the First, Second, Fifth, Sixth, and Eighth Amendments to the states, provisions that were initially conceived to apply only to the federal government. In so doing it was able to remove prayer from schools, remove religious symbols from public places, and restrict how adults prayed in public meetings.

Through its divined interpretation of privacy protections, the court then imposed new abortion laws upon the states, removing what was traditionally a state-based body of law and placing it at the feet of the federal courts. It also imposed requirements on states’ death penalty laws, and removed states’ power to limit the terms of its congressional delegates and senators, among countless other power-hoarding engagements.

Each of these actions was the result of decisions made by unelected officials permanently sitting upon the nation’s benches that would forever change the fabric of the Constitution and of the nation. And what recourse did the people possess to check the Supreme Court as it interpreted the Constitution in a manner inconsistent with their will?

Operationally, the answer, of course, is none. There is no amendment that will ever be passed to specifically overturn a Supreme Court opinion ruling that a crèche may not sit in a public building during Christmas; nor does Congress possess the authority to pass a law that would overrule the court when the latter speaks on issues of constitutionality, even if the matter were so obvious to Congress that it would have unanimously voted against court’s ruling.

Clearly, the Supreme Court’s ability to issue a binding opinion on any subject that no one else could overturn is wholly inconsistent with the system of checks and balances the Framers crafted. In fact, in the same 1820 letter to Jarvis, Jefferson observed, “The Constitution has erected no such single tribunal, knowing that to whatever hands confided, with the corruptions of time and party, its members would become despots.” Yet this is the situation in which we find ourselves today with the Supreme Court, both in the various states and within the federal government.

Let’s Solve This the Way Canada Did

So how do we rectify this unchecked runaway judiciary? Recognizing a similar threat to its democracy, Canada instituted Section 33 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedom in 1982 to allow for a legislative override. Under this provision, if a Canadian legislative body should find the opinion of the court inconsistent with the views of the electorate, the legislature could override or nullify the court’s ruling.

Canada is not alone in possessing such a provision. Australia, Israel, and England, among other great democracies, allow their respective legislatures to override even the highest rulings of their courts.

The reason for this is self-explanatory: no one in a republic ought to have plenary authority on practically any policy matter affecting the country, much less on ones defining the nature its foundational document. Doing so would not only mean subjecting that society to the despotic rule of one branch of government, but even more importantly, it would mean relinquishing control of the very fabric and ownership of its constitution to that group.

Recognizing this flaw in our national Constitution, I have crafted a proposed amendment that would permanently address this problem. It reads:

Any law, resolution, or other legislative act declared void by the Supreme Court of the United States or any District Court of Appeal may be deemed active and operational, notwithstanding the court’s ruling, if agreed to by Congress pursuant to a joint resolution adopted by a sixty percent vote of each chamber within five years after the date that the ruling becomes final. Such a joint resolution shall take effect immediately upon passage.

A legislative override provision, if enacted, would curtail activist judges. Of equal importance, it would allow the people of the United States to take back control of their Constitution. It would also force the people to engage the legislature in enacting rectifications to current laws that they see as objectionable or flawed, rather than run to the courts to impose their unconvincing will upon Americans.

In short, a legislative override provision to our Constitution would represent the clearest and most effective correction to the unchecked actions of an overzealous activist court. Indeed, a legislative override provision would place our nation closest to the vision President Washington shared in his Farewell Address:

If in the opinion of the people the distribution or modification of the constitutional powers be in any particular wrong, let it be corrected by an amendment in the way which the Constitution designates. But let there be no change by usurpation; for though this in one instance may be the instrument of good, it is the customary weapon by which free governments are destroyed.

A legislative override provision would prevent such usurpations from taking place and would, ultimately, save our free government.