Late spring is a time of last-days-of-classes and graduation ceremonies. For college professors like me, it brings a mixture of emotions–relief, pride in students’ accomplishments, as well as a sense of bittersweet finality. As we sense the window closing, genuine emotion as well as a bit of vanity lead us to try to say one last important thing to our students.

I don’t have a set end-of-year routine. Sometimes, I’ll try to go the dramatic route and read a powerful poem (whose meaning I may or may not entirely grasp). Other times, I’ll facilitate student reflection about the semester that’s passed. Or I’ll do the proven student-friendly thing and bring food to class.

Some teachers at this time of year are inclined to share a song with their students. There’s risk as well as reward in this. It always seems like a good idea when looking over your CD collection or iTunes playlist from the comfort of your family room. (“They’ve got good taste. They’ll love this song.”) In the classroom, though, the practice can backfire. Sharing music–especially popular music–is tricky. There’s no accounting for the musical tastes of twenty or thirty different people. And then there’s the passage of time issue, which middle-aged professors are notorious for forgetting about. (“Certainly you kids have heard of Bruce Springsteen? Dire Straits? R.E.M.? None of them? What’s wrong with you?!”)

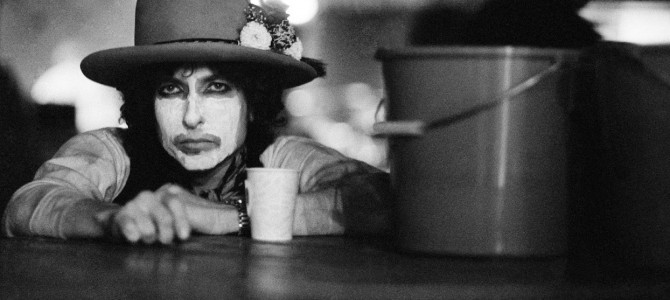

Despite these pitfalls, in recent years I’ve often ended my last class meeting of the year by sharing a song with my students–Bob Dylan’s “Forever Young.” I don’t choose it because it’s current or “relevant” as we tend to use this word. It’s an old song, ancient even from the perspective of students. Dylan recorded it for his 1974 album Planet Waves. At the time, Dylan was (as always) out of step with many of his musician friends and colleagues. In the mid-1960s, he turned away from politics and the limelight generally. After a traumatic motorcycle accident, he settled down, started reading the Bible voraciously, and focused attention on his growing family. This is one of the reasons many fans and students of Dylan view “Forever Young” as a song from father to child.

However, the song can also be heard as a benedictory prayer for young adults preparing to enter the next stage of their lives–whether more schooling or work or the unknown. That’s the spirit in which I share it with my students. Dylan recorded two versions on Planet Waves (the first a slow ballad and the second a fast country-rock number). It’s also been covered many times, including for television shows. But my favorite version which I share with students is Dylan’s simple and rhythmic solo demo version that was eventually released in the 1985 Biograph collection. As much as I like this interpretation, I don’t share “Forever Young” with my students for its musical qualities alone. As always is the case with Dylan’s songs, the lyrics are the thing:

May God bless and keep you always

May your wishes all come true

May you always do for others

And let others do for you

May you build a ladder to the stars

And climb on every rung

May you stay forever young

May you stay forever young

May you grow up to be righteous

May you grow up to be true

May you always know the truth

And see the lights surrounding you

May you always be courageous

Stand upright and be strong

May you stay forever young

May you stay forever young

May your hands always be busy

May your feet always be swift

May you have a strong foundation

When the winds of changes shift

May your heart always be joyful

May your song always be sung

May you stay forever young

May you stay forever young

Dylan’s “Forever Young” is a powerful benediction for young people graduating from high schools and colleges in today’s America for a number of reasons. For one thing, it’s a refreshing contrast to the generic, sappy, dumbed-down way in which religion (sorry–spirituality) is treated in many circles today. Many graduation ceremonies this spring will again be full of this kind of rhetoric. But Dylan’s lyrics are full of specific, concrete religious references. Among other things, the song contributes to students’ cultural literacy. It opens with the words of the benediction in Numbers 6: “The Lord bless and keep you.” There’s the allusion to Jacob’s vision of a ladder in Genesis 28 which connected earth and heaven and had angels continually ascending and descending it. Dylan’s wish for generosity given and generosity received descends from a myriad of reflections on the Golden Rule, including the prayer of St. Francis with its call for mutuality (to console and to be consoled, to love and to be loved).

In contrast to the educational spirit of the age, Dylan’s song is action-oriented. Listeners are encouraged to do, to climb, to grow, to be courageous, to stand fast, to have busy hands and swift feet. Although all listeners can find resonance in this, its tone seems especially relevant to one of the most pressing challenges of our time–the education of boys and young men. Mounting evidence suggests a problem in this area. Schools’ focus on feelings, dialogue, cooperation, and conflict-resolution doesn’t seem to be helping. Certainly, these are valid things for students to learn, but they’ve also had a long run by now. Students today especially need to hear that disciplined and principled action can be part of a good life well-lived.

Dylan’s song calls for courage, but not of the political and “prophetic” type so common in college graduation speeches today. Rather, Dylan calls listeners to do the tough, but un-dramatic work of following truth and righteousness in a world that often doesn’t recognize them. He reminds us of the satisfaction that comes from living good and honorable lives, and from encouraging future generations to do the same. Many commentators since 1974 have tried to read their own politics into “Forever Young,” claiming for instance that the song is about changing the world or human rights. Dylan’s own lyrics and the few comments he’s made about his music over the years suggest otherwise. His distinctive call to live hope-filled, courageous lives motivated by truth and righteousness is more needed than ever today.

And finally, Dylan’s “Forever Young” reminds us about the proper uses and potential virtue of youth. It’s possible to go off the rails on this in two different ways. Many of Dylan’s own contemporaries in the 1960s and 1970s fell into the cult of youth, believing that youth-driven political movements would bring needed revolution. Old folks would simply have to get out of the way. Dylan never really bought the idea of a stark generational divide. Not only did he seem to trust some people over thirty, he sought them out. Even as a young man, he had an old soul, trying to track down old bluesmen and folk musicians.

Today, we have a different youth problem. We have less self-righteous grandstanding, but seemingly more long-term immaturity. The status of adulthood is seen as either restrictive or unattainable, so why strive to reach it? Dylan’s song leads listeners to avoid both these missteps –but only if we listen to it in its entirety. If we hear only the refrain, the song can become a type of simple slogan we’re used to hearing in our political protests and pop culture. “Forever young” can be easily misinterpreted as either “fight the man” or “never grow up.” But this misses Dylan’s full hopes for the young. They’re neither revolutionary nor frivolous. His understanding of the virtues of youth is fuller and richer than what we often hear today.

The clichés of contemporary graduation speeches (“believe in yourselves,” “be change agents”) aren’t all wrong or bad. But they ring hollow without any moral footing. Dylan’s song “Forever Young” reminds us of this, and it’s a major reason why I like to share it with students at this time of year. When I’m feeling especially eloquent or a bit full of myself, I’ll try to reflect on the song beforehand. But usually I realize this is unnecessary and that the song stands on its own merits. So then I give students a printed copy of the lyrics, listen to the song with them, and finally wish them well before walking out the classroom door.

James B. LaGrand Professor of American History at Messiah College.