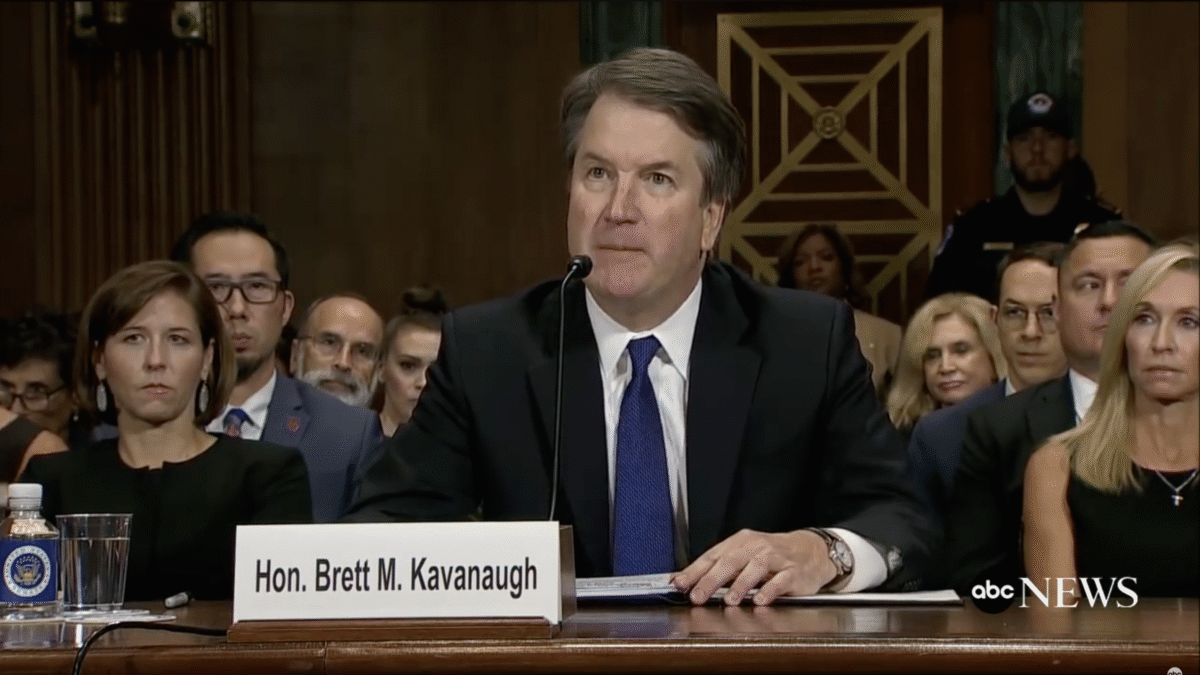

The Supreme Court ruled 6-3 that President Donald Trump’s tariffs under an emergency act are unlawful, a conclusion Justice Brett Kavanaugh said “does not make much sense” in his dissent.

Trump declared two national emergencies in early 2025, one addressing drug trafficking and the other trade imbalances with other countries — like China — that have harmed Americans. As a result, Trump imposed tariffs on several nations, including China, Canada and Mexico.

The Supreme Court held in Learning Resources, Inc. v. Trump and Trump v. V.O.S. Solutions Inc., that the use of the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA) “does not authorize the President to impose tariffs.”

But Kavanaugh, dissenting alongside Justices Clarence Thomas and Samuel Alito, tore into the ruling.

‘The Answer Is Clearly Yes’

Kavanaugh argued that IEEPA gives Trump broad authority to regulate international economic transactions during declared national emergencies, including the “importation” of foreign goods.

As Kavanaugh pointed out, “The sole legal question here is whether, under IEEPA, tariffs are a means to ‘regulate … importation.’ Statutory text, history, and precedent demonstrate that the answer is clearly yes: Like quotas and embargoes, tariffs are a traditional and common tool to regulate importation.”

But it apparently was not “clear” to the majority.

‘There Is No Good Answer’

Kavanaugh referenced historical precedent to back up his opinion, noting that President Richard Nixon imposed a 10 percent tariff on most foreign imports in 1971 under the Trading with the Enemy Act (TWEA), which authorized the president to “regulate … importation.” Such tariffs were upheld under that framing, which is the same language found in the IEEPA.

In creating IEEPA, as Kavanaugh wrote, Congress divided TWEA “into two separate statutes,” though “Congress retained that same ‘regulate … importation’ language in both laws — in TWEA for wartime and in IEEPA for peacetime national emergencies. In doing so, Members of Congress were plainly aware — after all, how could they not be — that the ‘regulate … importation’ language had recently been invoked by the President and interpreted by the courts to encompass tariffs.”

“If Congress wanted to exclude tariffs from IEEPA’s scope, why would it enact the exact statutory language from TWEA that had just been invoked by the President and interpreted by the courts to cover tariffs? Neither the plaintiffs nor the Court today offers a good answer to that question. Understandably so, because there is no good answer,” he continued.

Kavanaugh also noted that one year before IEEPA was enacted, the Supreme Court “unanimously ruled that a similarly worded statute authorizing the President to ‘adjust the imports’ permitted President Ford to impose monetary exactions on foreign oil imports.”

‘Heads in the Sand’

Kavanaugh also accused the majority of trying “to dodge the force of the Nixon tariffs by observing that one appeals court’s interpretation of ‘regulate … importation’ to uphold President Nixon’s tariffs does not suffice to describe that interpretation as ‘well-settled’ when IEEPA was enacted in 1977. Fair enough.”

“But that is not the right question,” Kavanaugh continues. “The question is what Members of Congress and the public would have understood ‘regulate … importation’ to mean when Congress enacted IEEPA in 1977. Given the significant and well-known Nixon tariffs, it is entirely implausible to think that Congress’s 1977 re-enactment of the phrase ‘regulate … importation’ in IEEPA was somehow meant or understood to exclude tariffs.”

“Any citizens or Members of Congress in 1977 who somehow thought that the ‘regulate … importation’ language in IEEPA excluded tariffs would have had their heads in the sand,” Kavanaugh wrote.

‘That Approach Does Not Make Much Sense’

Kavanaugh also questioned the rationality of the majority trying to limit the president’s authority while simultaneously allowing him a broader authority.

“The plaintiffs and the Court acknowledge that IEEPA authorizes the President to impose quotas or embargoes on foreign imports — meaning that a President could completely block some or all imports. But they say that IEEPA does not authorize the President to employ the lesser power of tariffs, which simply condition imports on a payment.”

“As they interpret the statute, the President could, for example, block all imports from China but cannot order even a $1 tariff on goods imported from China. That approach does not make much sense,” he wrote.

Kavanaugh ended his opinion by essentially arguing that the majority concluded President Trump merely “checked the wrong statutory box by relying on IEEPA rather than another statute to impose these tariffs” — even though IEEPA, under his interpretation, would have been sufficient.

“Although I firmly disagree with the Court’s holding today, the decision might not substantially constrain a President’s ability to order tariffs going forward. That is because numerous other federal statutes authorize the President to impose tariffs and might justify most (if not all) of the tariffs at issue in this case — albeit perhaps with a few additional procedural steps that IEEPA, as an emergency statute, does not require. “