December 13 marks the 50-year anniversary of mankind’s last excursion on the surface of the moon. On that day, Apollo 17 astronauts Eugene “Gene” Cernan and Harrison “Jack” Schmitt undertook their third and final venture outside their lunar module “Challenger.” Ronald Evans remained in lunar orbit in the command/service module “America,” photographing the sun and stars. The winged warriors retired from escorting their chosen ones through the sky.

Of the 24 American men who traveled that far from Earth, 10 remain alive today. Of those, half descended to the moon’s crust and left their footprints there. Only four continue to be with us, including Schmitt, the sole professional geologist among them. (Evans passed away in 1990, and Cernan in 2017.)

Our voluntary termination of these endeavors — after less than five years from achieving that milestone — leaves a melancholy reminder of foregone opportunities. Then again, maybe that lost ability wasn’t so important. After all, former New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo reminded us a few years ago, our country “was never that great.”

Some of us beg to differ.

The Apollo 17 emblem features the Hellenic sun god Apollo of Belvedere as a golden sculpture portrait, including a stylized eagle, the moon, Saturn, and a spiral galaxy. Around the grey border reads “APOLLO XVII” and the astronauts’ surnames. All of the manned Apollo missions (except Apollo-Soyuz) identified their designations with either Roman or Hindu-Arabic numerals, and most included the crew, the exceptions being Apollo 11 and Apollo 13.

Of the manned missions that involved Apollo spacecraft, five were launched on the Saturn IB: Apollo 7, Skylab 1, Skylab 2, Skylab 3, and Apollo 18 (that docked with Soyuz 19 on the first and only American-Soviet joint orbital mission). The remainder launched on the behemoth Saturn V with 4,000 tons of thrust from 1968 to 1972. The last Saturn V launched America’s first space station “Skylab” in 1973.

A pair of articles on Apollo 11 provides a brief overview of Saturn V’s development. Six missions successfully landed on the moon, and one (Apollo 13) had to abort. Not only was Apollo 17 the program’s finalé, but it also featured the sole launch at night. The awe-inspiring image of the fiery torch rising in the night sky lends visual testimony to human creative ability when assigned a herculean task.

Apollo 17 was former Navy aviator Cernan’s third and final spaceflight. He had previously flown on Gemini 9A to practice rendezvous and docking and Apollo 10 as a dress rehearsal for the first lunar landing. This was the first and only space mission for Evans and Schmitt, the latter of whom later served as senator from New Mexico from 1977-1983.

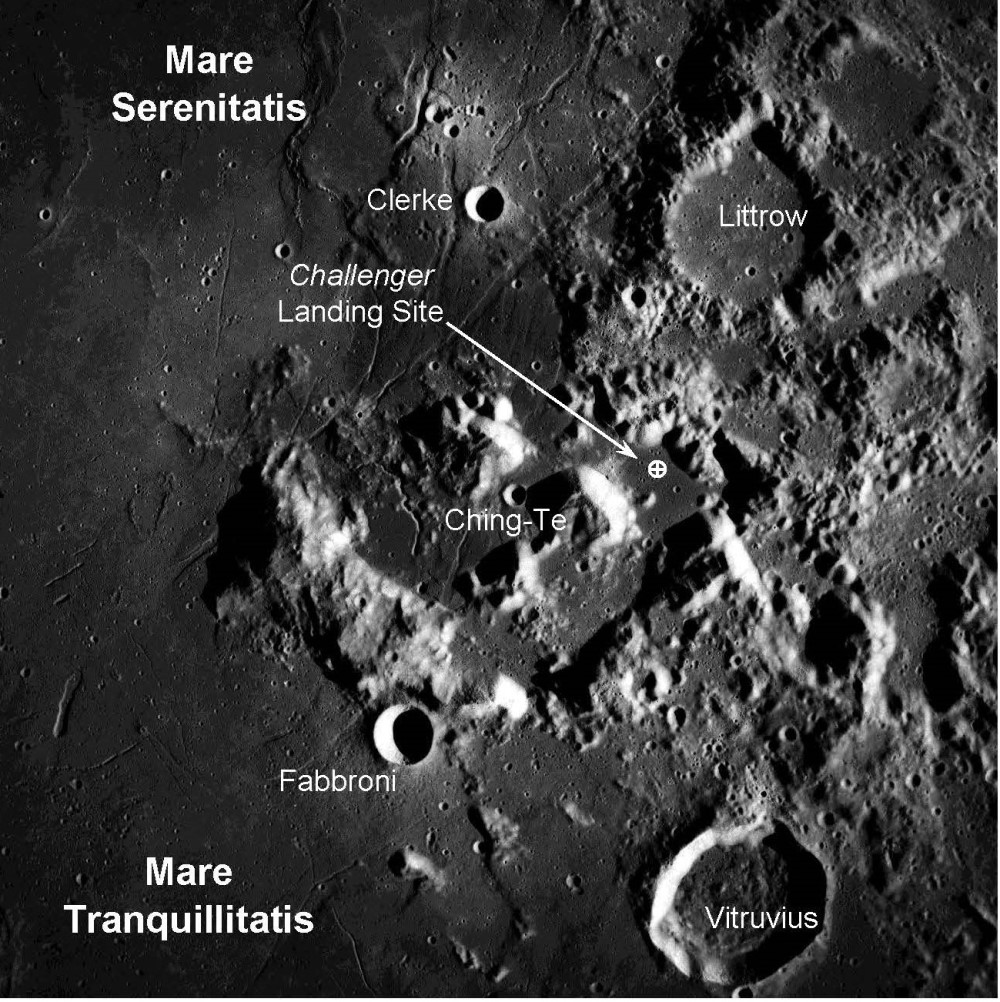

Following its Florida launch a half-hour after midnight EST on Dec. 7, Apollo 17 spacecraft “America” and “Challenger” docked and entered lunar orbit three days later. The lunar module “Challenger” with Cernan and Schmitt descended on Dec. 11 and touched down in the Taurus-Littrow valley at the southeastern edge of Mare Serenitatis (i.e., Sea of Serenity). The orbital photograph below marks their landing location.

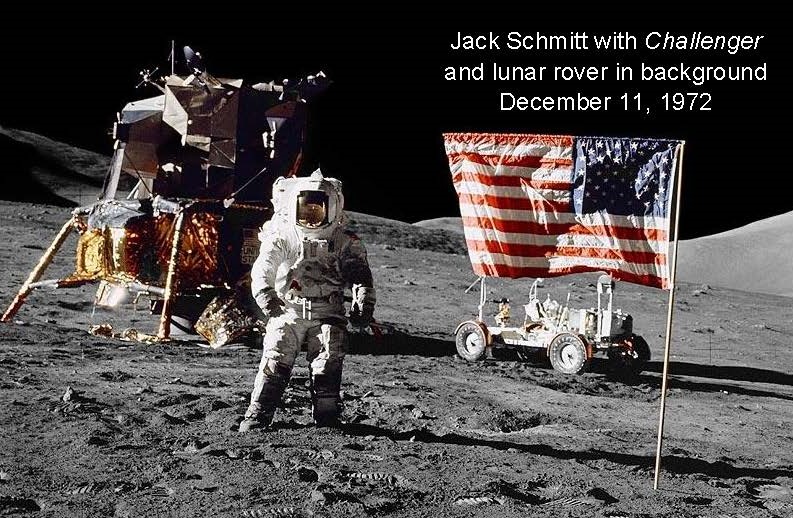

Soon after, Cernan and Schmitt egressed the upper stage of “Challenger” to plant the American flag and explore. Apollo missions 15, 16, and 17 carried a lunar rover to extend the astronauts’ travel distance considerably, by more than four-and-a-half miles from the landing site. They took three excursions, each lasting more than seven hours.

Cernan and Schmitt deposited nuclear-powered instruments in the Apollo Lunar Surface Experiments Package (ALSEP) left behind around the landing site. Measurements included gravimetry to map material distributions based on their densities, mass spectrometry to examine atmospheric composition, and seismometry to detect quakes. Other devices investigated dust particles and thermal emissions from the core.

ALSEP continued to provide scientific data until 1977, when reception was suspended for budgetary reasons. The rover also carried various experiments, including instrumentation to learn the electrical properties of rocks. More than 240 pounds of moon rocks and soil samples from 22 locations were retrieved and returned to Earth for further analysis.

Following the launch of the lunar module’s upper stage from the moon’s surface on the evening of the 14th, Evans docked the command module so Cernan and Schmitt could rejoin. On the 17th, Evans undertook a spacewalk from the command module to retrieve measurement equipment (including cameras, a spectrometer, and an altimeter) from the service module’s instrument bay.

The astronauts detached the command and lunar modules, and “America” broke lunar orbit for home, after which the service module separated. After re-entering Earth’s atmosphere, the command module splashed down in the Pacific Ocean. It was retrieved by the Essex-class aircraft carrier U.S.S. Ticonderoga (CVS-14) on Dec. 19, the same carrier on which Evans had served as a naval pilot before joining NASA. Thus completed the final act of America’s manned moon-landing program.

In the concluding scene of the movie “Apollo 13,” Tom Hanks as astronaut Jim Lovell muses, “When will we be going back, and who will that be?” What plans does the United States have to finally return to that “magnificent desolation,” in the words of astronaut Buzz Aldrin?

Presently, NASA commits resources to the Artemis program. It incorporates the Orion spacecraft to be lofted by the Space Launch System that rivals the venerable Saturn V for ground thrust. That weight limit may soon be overtaken by the gargantuan “Starship” designed and built by SpaceX.

Artemis expects to return people to lunar orbit on its second mission by mid-2024. Later that year, electrical power and life support can be sustained by Gateway, a modular docking platform to be inserted piecemeal into an elliptical polar orbit around the moon via SpaceX’s Falcon Heavy.

Assuming this ambitious schedule holds, a planned landing at the south polar region can commence on its third mission the following year. Competing contenders for the lunar lander include a modified SpaceX Starship and independent designs from Blue Origin and Dynetics. Humans can then perambulate on our nearest celestial orb once again.

Some scolds may complain that such funding for lunar return should be spent instead to mitigate problems on earth. Such contentions sound rather self-serving given past and present political priorities. The Apollo project total cost in current dollars is about the same as its contemporary exercise. The Vietnam conflict and the War on Poverty dwarfed both.

Which of these pursuits successfully achieved its aims? The one not botched by paper-pushing Ivy League-graduate narcissists. With discrete and attainable goals, those who know how to bend metal and calculate moments of inertia can accomplish astonishing feats of engineering and expand our horizons of scientific understanding.

President Kennedy implored America to undertake an audacious quest, while satirically asking “Why [go to] the moon?” during his address at Rice University. Norwegian explorer Fridtjof Nansen encapsulated this imperative by his observation regarding anthropological curiosity: “The history of the human race is a continual struggle from darkness into light. It is, therefore, to no purpose to discuss the use of knowledge; man wants to know, and when he ceases to do so, he is no longer a man.”

Genesis 1:28 compels us to subdue our world, by exploration and technique, and cis-lunar space belongs to humanity. That’s why.