On rare occasions, the secular and sacred elements of culture converge in poetic symmetry. Today, as Christians around the world commemorate Christ’s passion and death, Americans celebrate 75 years since baseball’s color line finally fell.

When churches today read from the Old Testament prophet Isaiah, whose song of a suffering servant presaged Christ’s crucifixion, we can also recall how Jackie Robinson suffered to make America a better society, and Americans a better people.

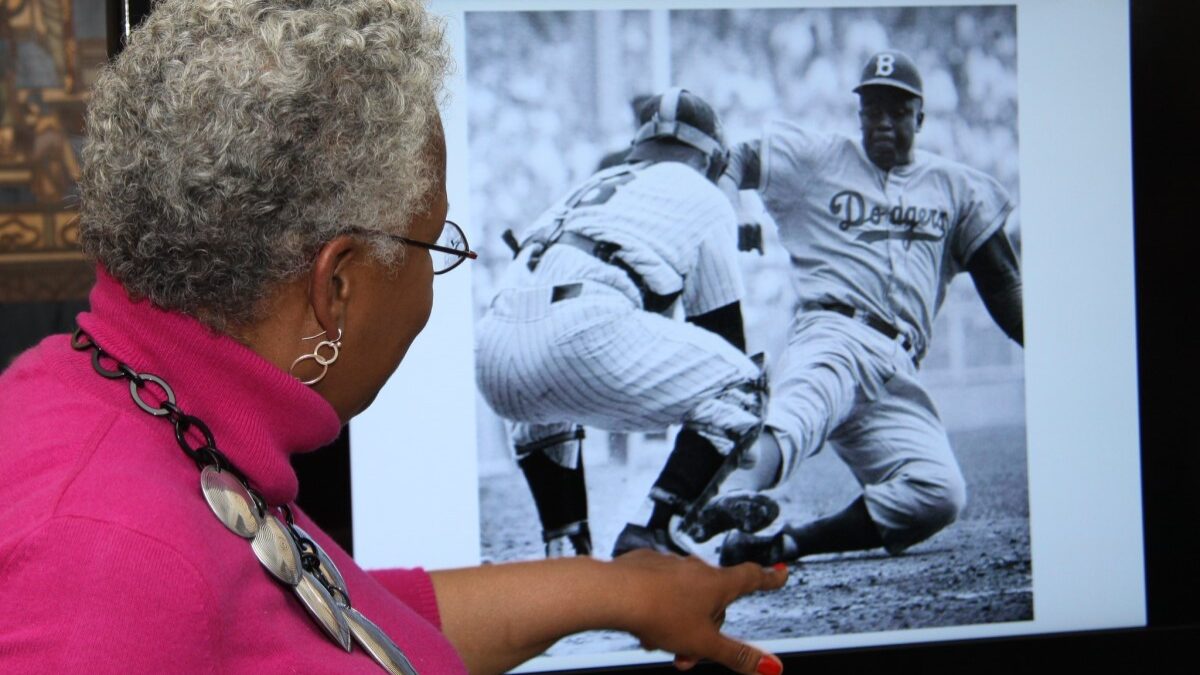

Unlike Isaiah’s servant, Jack Roosevelt Robinson did have a “stately bearing to make us look at him,” and an “appearance that would attract us to him.” A four-sport letterman at the University of California at Los Angeles, Robinson starred on the football team while winning the national championship in the long jump. During World War II, he was accepted into Officer Candidate School and commissioned as a second lieutenant.

But breaking baseball’s color line required a skill far beyond physical dexterity—one Robinson did not know whether he could muster. He admitted that “all my life I had believed in payback, retaliation.”

When in the Army, he had faced court-martial for refusing to move to the back of a bus. He was eventually acquitted, but could someone who considered his dignity “the most luxurious possession, the richest treasure,” agree to, as Robinson put it, “sell [his] birthright?”

Brooklyn Dodgers owner Branch Rickey made Robinson promise not to retaliate against any racist taunts, jeers, or threats for his first three years in the majors. To win over a baseball establishment highly skeptical of integration, Robinson faced the same treatment as Isaiah’s servant: “Though he was harshly treated, he submitted and opened not his mouth; like a lamb led to the slaughter or a sheep before the shearers, he was silent and opened not his mouth.”

The prejudices he faced said much more about American society than Robinson, again echoing Isaiah: “It was our infirmities that he bore, our sufferings that he endured.” Philadelphia Phillies manager Ben Chapman spearheaded such vicious bench-jockeying that Robinson later wrote he wanted to explode with rage. Yet when the abuse led to a backlash that jeopardized Chapman’s job, Robinson graciously agreed to pose with a man who had baited him with racist taunts.

The insults didn’t just come from the opposing dugout. Robinson’s own manager with the minor-league Montreal Royals in 1946, Clay Hopper, used a racial epithet to ask whether African Americans were even human beings.

But at a time the armed forces remained segregated, and Martin Luther King Jr. was still in college, Robinson’s on-field achievements despite these indignities began converting the hearts and minds so critical to the civil rights movement’s success. Longtime Dodger broadcaster Red Barber spoke for many Americans when he admitted, “Robinson did more for me than I did for him,” making him recognize that “I had to change my outlook on racial equations… I had to begin thinking differently.”

Once he had successfully integrated baseball, Robinson would regain the voice he had temporarily sacrificed. Later in his life, he criticized black separatists as too radical—and the NAACP as too timid. He kept pushing for his vision for civil rights, based on “the ballot and the buck,” at a time others might have rested on their laurels. After the price he had paid, he could not do otherwise.

But the stress had taken its toll. Staying silent “ate him alive,” as one historian put it. Red Barber believed the abuse, and Robinson’s inability to respond to it, hastened his demise: “They said that Robinson died from diabetes and other things. I think he died from the load he carried.”

His Kansas City Monarchs teammate, Sammie Haynes, put it more bluntly: “He knew he had the whole black race, so to speak, on his shoulders. So he just said, ‘I can take it. I can handle it. I will take it for the rest of the country and the guys.’ And that’s why he took all that mess. And it killed him.”

“If he gives his life as an offering for sin, he shall see his descendants in a long life, and the will of the Lord shall be accomplished through him.” Fewer Americans epitomized these words from Isaiah more than Jack Roosevelt Robinson, and fewer to more profound effect.

As Christians worldwide hear those words this afternoon, 75 years to the day after he first stepped onto the grass of Brooklyn’s Ebbets Field, people of all faiths, colors, and nationalities can resolve to emulate Robinson’s heroic example of sacrifice in pursuit of the good.