Kyle Sammin cogently argues that the United States should implement a voluntary national identity system in the wake of the Equifax hacking. Debate about this issue has roiled for decades. Although numerous countries have a national identification system, Americans have long resisted the idea.

The Social Security number (SSN) has certainly expanded beyond its original purpose of serving as an account number for benefits, but policy-makers have repeatedly rejected calls to convert it into an identifier. The Clinton administration’s 1993 proposal of a “Health Security Card” never got off the ground, and even after the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks, Congress made clear in creating the Department of Homeland Security that DHS was not authorized to create a national ID system.

The reason for this attitude is clear: Americans traditionally treasure their privacy, and anything that smacks of government surveillance and tracking has always been considered fundamentally un-American.

But the siren song of wondrous modern technology calls some to revisit the issue. Although Sammin acknowledges Americans’ suspicion of federal identity-tracking, he argues that SSNs, passports, and federal mandates on state drivers’ licenses (through the Real ID Act of 2005) already create federal involvement. He decries the “hodgepodge of barely functional documents issued by the federal government combined with federal coercion in how the states issue their own IDs.” The feds are already there, he argues, so we may as well accept it and implement policies to protect identities better than credit-reporting agencies do.

It’s Preposterous to Say the Feds Can Manage Data Better

At the outset, let’s dispose of the contention that the federal government can keep personal data secure. The 2015 breach of the Office of Personnel Management’s data system exposed sensitive data, including SSNs, of approximately 21.5 million people. Apparently the hackers successfully struck not once, but twice. OPM officials admitted that the data had not been encrypted or otherwise protected because the computers were too old.

That same year, hearings of the House Government Operations and Oversight Committee revealed the shocking absence of data security at the U.S. Department of Education, putting at risk highly sensitive information of, for example, individuals and families applying for student loans. In other words, the proposition that the federal government should be entrusted with even more information on citizens is a bit of a high-stakes gamble.

The types of information contained by this sophisticated new national ID card would inevitably go well beyond the nuts and bolts needed to establish identity. Sammin argues that credit-reporting companies already have citizens’ data, but their trove is limited to financial information. What he and the scarier data-mongers contemplate is much more than this, including biometric information. The recently created Indian “Aadhaar” system, which he praises, includes fingerprints and iris scans.

Mandatory Programs Often Start as Voluntary

The Indian system is worth a second look. Aadhaar began as a voluntary program designed to reduce fraud in government benefits programs, but according to a BBC report, “it has become virtually impossible to do anything financial without it – such as opening a bank account or filing a tax return.” It’s almost certain that any “voluntary” program in the United States would undergo the same evolution, just as Social Security numbers have.

To obtain the biometric information for Aadhaar, the government sucked up all data taken from individuals during their contacts with government agencies—schools, hospitals, childcare centers, and special camps. Indians thus have no choice about whether government will store and use their most personal data. Despite the government’s assurances that the system is secure, doubts skyrocketed in March 2017 when cricket star MS Dhoni’s Aadhaar number appeared on Twitter. So not only has the new system already transitioned from voluntary to mandatory, it has already been breached in at least one high-profile case.

What if biometric and other data from a national ID card is lost, hacked, or stolen? The Electronic Frontier Foundation says loss, theft, or damage occurs with up to 5 percent of all national ID cards every year. You can always change your credit-card number, but you can’t change your fingerprints or your iris. So the system instituted to safeguard your identity would create an identity nightmare once criminals access people’s most sensitive data.

The Electronic Frontier Foundation warns, “National ID cards and the databases behind them comprise the cornerstone of government surveillance systems that creates risks to privacy and anonymity.” Worse, “[t]he requirement to produce identity cards on demand habituates citizens into participating in their own surveillance and social control.”

In addition to coercion and security breaches, a troubling aspect of a national identification system is “mission creep”—the temptation of government busybodies to use data they vacuum up for more than identification purposes. Consider the work of the U.S. Commission on Evidence-based Policymaking (CEP). This commission was created to examine how the federal government might combine and use the citizen data collected by various agencies (USED, the Internal Revenue Service, Health and Human Services, etc.) to assess government programs. Throughout a year of hearings, CEP considered testimony from many witnesses, mainly those advocating extensive disclosure of data among agencies and researchers and tracking citizens for life by connecting their employment data to their education data, all in the name of “transparency.”

The Appetite for Your Personal Information Is Enormous

A witness from a predictive-analytics company (Booz Allen Hamilton, the former employer of Edward Snowden), pushed a centralized database drawing from multiple federal sources: “[E]ligibility and participation tracked by the Social Security Administration – when combined with taxpayer data and tax subsidies from the IRS, survey data from the U.S. Census Bureau, and data from other agencies, such as HHS and HUD – could exponentially . . . enhance our potential to draw insights that could not have been derived before.”

Although CEP’s final report didn’t go that far, it did recommend increasing researcher and government agency access to every agency’s data. Such enthusiasm for even more data-swapping among agencies isn’t considered “fringe” in the world of data enthusiasts, such as the Gates Foundation-funded Data Quality Campaign. The question isn’t whether the data linked to the ID card will be expanded, but when.

What might the feds eventually do with this sensitive data? With Booz Allen-type algorithms, maybe bureaucrats can predict how individuals or groups might behave (“Minority Report,” anyone?). Or now that the government essentially controls health care, a citizen’s biometric data, perhaps including genetic information, could allow the government to manage his or her health-care or lifestyle choices. Mr. Chubby, we expect to see your ID card scanned at the gym three times a week.

Expanded non-biometric data is a problem as well. Your school records show a suspension for fighting in the eighth grade? Too risky to let you buy a gun 20 years later.

Data Is Power, and Concentrated Power Corrupts

Sammin recognizes these dangers, warning that “[t]he federal government should be careful not to take the idea too far” and shouldn’t use the national ID as an internal passport system. But who seriously believes the feds will respect their constitutional bounds? Ask any governor, any physician, any teacher. The innocent confidence that the monster can be controlled is inconsistent with all of history, and with common sense.

Trust in federal bureaucrats not to misuse data is also unwarranted. Examples abound: the FBI illegally discloses sensitive intelligence data on a “staggering” scale; IRS persecutors have transmitted a taxpayer’s confidential data to other agencies to ramp up harassment based on her political beliefs; a Social Security Administration employee illegally accesses confidential records as part of a fraud scheme. Men are not angels, and data they they can access about other people to should be strictly limited.

But the most fundamental objection to a national ID system is this: By what authority does any government require innocent citizens to turn over even their biometric information for its use? In a free society, “efficiency” and “ability to do cool things with it,” or even “it’s for their own good,” are not killer arguments. These arguments are those of a police state.

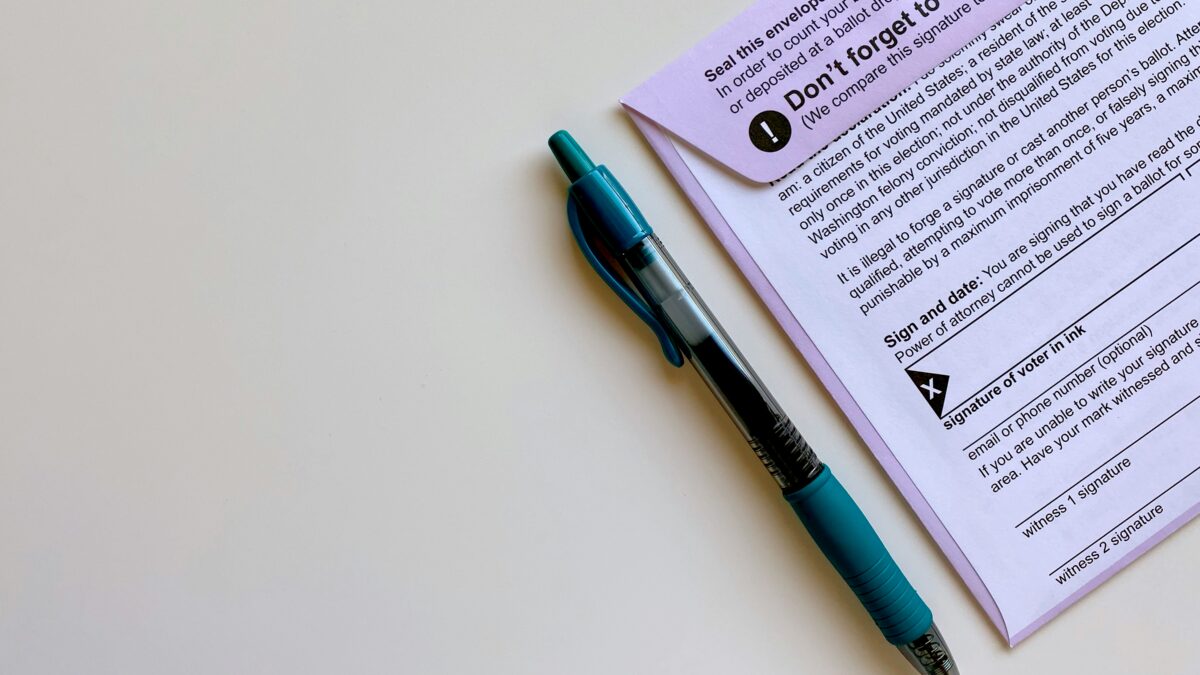

It may be that a national ID card could help with voter ID, or illegal immigration, or law enforcement (to what degree is debatable). But a free society must live with limits and tradeoffs. A free society recognizes that some lines are not to be crossed, some areas of human life not to be probed or recorded. As the Fourth Amendment says, the “right of people to be secure in their persons, papers and property, shall not be infringed.”

Americans have seen too much erosion of their privacy and autonomy. A national ID card is a bridge too far.