From 1950 to 2015, for every new student they enrolled, U.S. public schools hired nearly four full-time staff, most of whom weren’t teachers, according to a new EdChoice report from economist Ben Scafidi. While public schools hired teachers two and a half times as fast as they added students, they hired more than seven times as many non-teaching staff in that time.

Student achievement did not notably increase over the same period. In fact, it tanked in the 1960s and ’70s and has never recovered. Graduation rates are also down since 1970.

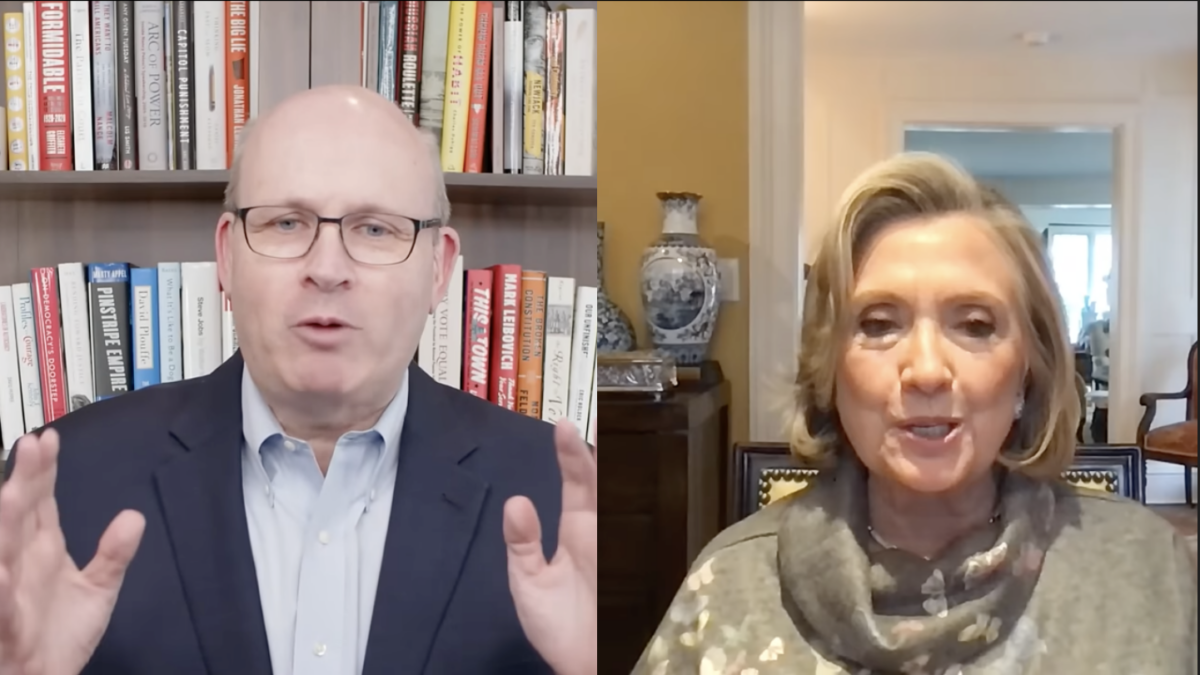

Scafidi has been researching this trend since 2012. In a podcast, he said he got the idea to study it by talking with his kids’ public school teachers, who expressed frustration about the ever-increasing bureaucracy they had to deal with. He decided to see if the stats bore out their frustrations. They do.

Scafidi also found that while taxpayer spending on public schools has increased 27 percent since 1992, teacher salaries overall have decreased 2 percent in that time in inflation-adjusted terms.

“It could be argued that this staffing surge was worth it in the 1950s, the 1960s, the 1970s, the 1980s, and early 1990s because during those decades public schools began welcoming students with special needs and were allowed to integrate by race or were actively integrated by government policies,” the report says. “But, the staffing surge has continued even after its first 42-year period that ended in 1992. The modern staffing surge, which began in 1992, has been expensive for taxpayers and has posed a tremendous opportunity cost on teachers and parents.”

We’re Compounding Our Bankruptcy

If U.S. public schools had hired staff proportional to student enrollment since 1992, they would have saved taxpayers $35 billion every year, for a total $805 billion wasted through 2015, the report says. It notes this money could have funded any number of things, including a $11,100 raise for every American teacher, granting 4 million students school choice, or backfilling the $500 billion in pension debt currently accrued on teachers’ behalf. That’s the current gap between what politicians promised to pay teachers after retirement, and what projections say will be available to fulfill those promises.

Public pension woes, besides squashing the economy for all of us, pinch another $6,800 out of the average teacher’s pay each year. Most teachers never see that money. It’s filched because politicians over-promised benefits and chose to spend the money teachers needed reserved for fully funded pensions. That’s how public schools’ hiring bloat is “burning the candle at both ends,” Scafidi noted in the podcast, because not only did schools waste money in hiring extra staff but all the extra staff tap pension systems that are already set to go bankrupt.

Here’s some back-of-the-envelope math using federal statistics to further illustrate what has been going on in classrooms. The average U.S. public elementary school class size is 21 students (secondary schools have bigger class sizes), and U.S. taxpayers pay an average of $12,300 per public school student per year. That’s $258,300 we’re spending per classroom per year.

Now, salary plus benefits for the average elementary school teacher come to about $80,000 per year. That’s a pretty good take for folks whose usual competing job opportunities offer significantly lower compensation. Like millennials pitching part of their salaries into the abyss of an also-bankrupt Social Security and Medicare that has paid many baby boomers more than they contributed, not only are teachers screwed through pension withholding, all the extra non-teaching staff depress their salary potential. In this hypothetical average classroom, $178,300 remains to be spent after shelling out for the teacher’s salary. That’s 69 percent of classroom spending going outside the classroom.

Now, not all teachers have full classrooms, notably many special education teachers. Like I wrote, this is a back-of-envelope calculation. But I think it’s illuminating.

Who’s Paying the Piper? And Where Is His Money?

Here’s another shocker. During the Great Recession, we heard wails from every corner of government all the way up to President Obama and his Education Secretary Arne Duncan about “teacher layoffs.” Yet Scafidi found that during the recession teachers, not administrators or non-teaching staff, were more likely to get fired. Administrators were least likely to lose a job.

After the recession subsided, the report says, schools resumed their historical pattern of hiring faster than enrollment growth with an emphasis on non-teaching staff. So it turns out that Scafidi’s kids’ teachers were right: public schools are bureaucracy-heavy. And teachers are the ones who most directly lose from this arrangement, which directly affects their students. After all, what’s the whole point of school? Lots of folks may have forgotten, but it’s learning. Creating contributing citizens.

If the United States is essentially a “pension plan with an army,” as the quip goes, our public schools are increasingly a welfare system with some classrooms, especially as they continue to build out into modern orphanages offering breakfast, lunches, and dinners plus wraparound social services plus medical care. That’s where this trend is taking us, although probably public pensions will belly-up before we get full Harlow’s monkeys.

These extrapolations are mine. Like most economists, Scafidi sticks to his data. But he does note that the modern staffing surge, the one that can’t be explained away by pointing to racial and special-needs integration, coincided with a dramatic growth in federal and state education regulations. It’s no coincidence that 1992 was the year President Bill Clinton signed a law called Goals 2000. It expanded federal jurisdiction over what teachers teach by, like President Obama’s Race to the Top program that pushed Common Core, giving states an offer they couldn’t refuse to subject curricula and testing to federal approval. My new book includes a whole chapter explaining the one-way ratchet that has only tightened since.

Scafidi points out a political dynamic that comes with expanded federal power over education: increased regulation blurs the lines of jurisdiction. This allows all three levels of government to blame the the other two for any problem: “By having each level and each level has their own preferences… so you just layer it on, layer it on, there’s your staffing surge,” Scafidi says.

The more levels of government that interfere with a school, the more waste, fraud, and abuse its leaders can get away with because it’s not clear who is responsible for what. That is one of the reasons I support eliminating the middle men and making parents and teachers directly accountable to each other. That directly improves education and accountability for it, not faux, government-driven “accountability” regulations that largely enrich and empower bureaucrats at the expense of teachers and kids.