Let me start my tale of Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.-inspired minor terror by saying I don’t blame any of the black students at Stadium High School for what happened on that day more than 20 years ago. It’s probably not what I would have done, but who knows? They had their reasons and were remarkably restrained, considering.

I was taking a public speaking class at Stadium in Tacoma, Washington, later made famous as the set of the movie “Ten Things I Hate About You.” One of our regular assignments was delivering announcements over the building’s PA system: half day tomorrow, school pep rally Thursday night, etc. We also did history bits.

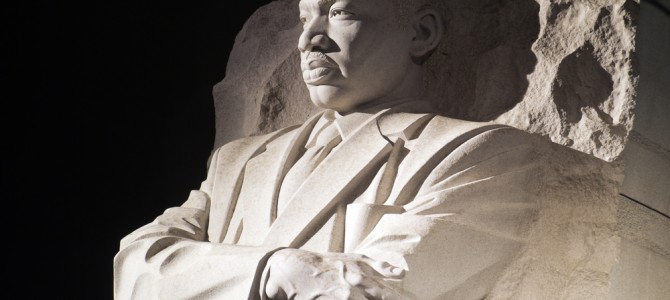

It fell to me to mark King’s “I Have a Dream” speech by reading a small excerpt to the whole school. That got me all kinds of excited. “I Have a Dream” is a great speech, whatever your political leanings are. It is intelligent, vivid, and concise, clocking in at under 1,700 words.

The speech is also daring. King used his whole bag of tricks to challenge everyone who would hear his poetical words at the National Mall on August 28, 1963, from Southern segregationists to Northern white liberals to would-be black militants. King preached that the American Founders had written a check to all Americans that had long since come due. He put the nation on notice that his great movement meant to cash it without delay. They would meet “police brutality” with “soul force,” and they would triumph.

It Was So Inspiring I Had to Try

And the words! Listen to how he describes the conflict: “seared in the flames of withering injustice”; “the tranquilizing drug of gradualism”; “the whirlwinds of revolt”; “the high plane of dignity and discipline”; “the jangling discord of our nation”; George Wallace’s lips were “dripping with the words of ‘interposition’ and ‘nullification.’”

King even manages to turn American topography into something you want to hear more about: “the mighty mountains of New York”; “the heightening Alleghenies of Pennsylvania”; “the curvaceous slopes of California.”

The best way to do King’s speech justice, I naively thought, would be to deliver it in the voice of King himself. After a brief intro, I, a white boy from the Pacific Northwest with our almost accentless English, tried to sound like a well-spoken, booming black preacher from the South. My voice had barely changed at that point, but I reached down deep and found the bass to tell students about “my” dream, “deeply rooted in the American dream.”

I quoted the most-quoted part of the speech, of course, where King hopes that “One day on the red hills of Georgia, the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners will be able to sit down together at the table of brotherhood. … One day even in the state of Mississippi, a state sweltering with the heat of injustice, sweltering with the heat of oppression, will be transformed into an oasis of freedom and justice. I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character. I have a dream today!”

In the allotted time, I tried to work in some of the preacher’s more blatantly religious language. How often do you get to tell all the students in a public school about a dream in which “every valley shall be exalted, and every hill and mountain shall be made low, and the rough places will be made plain, and the crooked places will be made straight and the glory of the Lord shall be revealed and all flesh shall see it together”? I closed with “the words of the old negro spiritual: Free at last! Free at last! Thank God Almighty we are free at last!”

What Happened Next Shocked Me

Next period, fishing for a compliment, I asked friend if he’d heard me on the intercom. His answer shocked me. The conversation went something like this:

Friend: We all heard it.

Me: How did it sound?

Friend: Do you want to get your ass kicked?

Me: What? No. What are you talking about?

Friend: You just read a Martin Luther King speech sounding like a black person.

Me: I was going for more Southern than black, but so what?

Friend: And you don’t see a problem with that?

Me: No! That’s how King delivered it.

Friend: But you’re white.

Me: So?

Friend: (Shakes head.) I’d watch your back.

He had a point, it turned out. That day, African-American students at Stadium kept accidentally bumping into me in the hallways, including one nudging-up-against-a-locker incident. No punches were thrown and no threatening words were exchanged in any of this.

Without my friend’s warning, I would have written it off as an unfortunate coincidence. Now that I was paying attention, the repeat collisions and several nasty looks worried me that something far worse was brewing after school.

Let’s Get Outta Here

That, in turn, created a moral dilemma and a PR nightmare. Fighting was one thing, yet fighting over the legacy of Martin Luther King Jr. seemed extra wrong and perverse. Imagine being known for having instigated The Great “I Have a Dream” Throwdown of 1993 when you were trying to celebrate, not mock, King and you may begin to see my problem.

So I got out of there. I called home for a ride to avoid conflict at the bus stop and exited the building by a different route than usual, just to play it extra safe. “What’s going on?” Dad asked when he pulled up into the school turn-around. “Just drive!” I said, easing down in the seat as far as I could.

The next school day was the real test. I showed up expecting the worst, but there were no collisions, no thrown elbows, and no locker presses from my fellow black students over the perceived insult. Maybe they worked it out of their systems with the previous day’s hilarious clumsiness, or maybe they thought about it and decided something about King’s message was worth not fighting over. I’ve always wondered which it was.