When it comes to enriching and expanding our imaginations toward a deeper, fuller, and healthier vision of work and economics, television can be a powerful tool. Shows like “Dirty Jobs,” “Shark Tank,” “Undercover Boss,” and “Restaurant Impossible” have used reality TV to illuminate the deeper meaning and transcendence of mundane toil and everyday economic exchange.

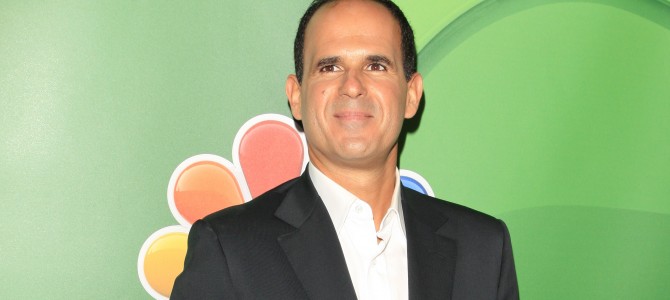

Now, kicking off its third season in less than two years, CNBC’s “The Profit” brings the genre to even greater heights. Starring Marcus Lemonis, a Lebanese-born American entrepreneur and investor, the show features struggling small businesses in desperate need of capital and restructuring, from restaurants to auto shops to toy companies to fashion boutiques to sports facilities and beyond.

Offering cash and business acumen for equity (and sometimes more), Lemonis dives into each situation with gusto, rapidly identifying the core problems and rolling out specific solutions to get things back on track. Unlike other shows in this category, things don’t always work out, often resulting in anti-climactic conclusions that leave one depressed and longing for renewal where businesses continue to flounder. Yet, when taking it all in on the whole, one can’t help be inspired at the power and potential of these enterprises, and more importantly, the people behind them.

Each episode is its own morality tale, highlighting the importance of properly oriented work, the transformative power of wise stewardship, and the danger and destruction of blind ambition and selfishness. These lessons intersect and overlap, but here are three key things the show teaches us about the beauty of business and its ability to channel our labor in the service of others.

1. Business Is Fundamentally About People

“It’s not really just a business show,” Lemonis said in a recent interview. “There are business lessons…but it’s not really a business show.” Lemonis consistently says he focuses on “people, process, and product,” but it’s that first bit—the people—that always takes up the most of each episode. In the end, it is people who either stand in the way of success or lean on his guidance, however painful, to propel and accelerate their business growth.

This is a simple point, to be sure, but whether we’re discussing macroeconomic policy or the merits of one business model over another, it’s a basic fact many often forget.

In the episode about COURAGE b (see video below), we see a severely fractured relationship between a mother and son that poisons the entire business. With 1 800 Car Cash, the issue is feuding brothers, each unwilling to acknowledge the gifts of the other, and both with their own degrees of foolishness. With Planet Popcorn, it’s a disorganized owner unwilling to change, and with candy shop Sweet Pete’s, it’s an overly carefree owner being exploited by an overly manipulative business partner.

At the bottom of every single business failure is some failure of people, and it goes well beyond skills and work ethic. Conflicts in business involve conflicts in creativity, and in turn, force us to reckon with who we were created to be and what we were created to do.

When success is achieved, these features shimmer and shine. We see the gifts of these owners and their employees coordinated in harmony and poured out for the good of society. Mitt Romney will continue to be mocked for his refrain that “corporations are people” but, as any worker should know and as this show thoroughly reminds us, these supposed “machines” don’t run by themselves.

2. Work and Wage Are a Powerful Combo

Nearly every episode involves a struggle between work and wage. Are the key givers and contributors making what they ought? Are the idle and destructive workers exploiting the system for personal gain?

Politicians, labor unions, and mainstream academia will propose that we take a steamroller to this tension, flattening wages (and in turn, gifts) under the banner of “justice.” In a refreshing contrast to such attitudes, “The Profit” shows what a real “just wage” actually looks like, and how it has less to do with artificial minimums and maximums and more to do with uniting gift-givers with the rest of civilization.

With wine store Amazing Grapes, the owner seems to enjoy neglecting his employees and could care less whether and what they’re paid. With A. Stein Meat Company, Lemonis offers to bail out the employees after things go sour, and the owners still manage to flake out in an attempt to preserve their own little pile (spoiler alert).

Lemonis often takes away people’s pay or fires them if they’re not pulling their weight. But the lesson here is most evident in the episode on Key West Key Lime Pie Shoppe, where one of the best and hardest workers, Tami, is severely underpaid and undervalued. Lemonis immediately recognizes her contributions and responds by offering to pay for her upcoming maternity leave and boost her salary so she doesn’t have to work two jobs (see video below). After the show aired and she continued to add value, Lemonis decided to give her 25 percent of the business.

It is impossible to not be moved by watching that kind of weight be lifted and to see someone’s work and sacrifice so justly rewarded. Wages are important for paying the bills, to be sure, but when justly arranged and poured out—not by government edict or coercive dictate—they also prove a transformative force in accelerating authentic flourishing across individual lives and entire enterprises.

As Lester DeKoster notes: “[T]hose whose work is concerned with the creation and administration of wage and price scales must be economic artists whose jobs bear heavy moral responsibility….The twin tracks of work and wage…are bridged by morality, not mathematics. And it is in the self-sculpting choices of wage and price scales that managers must make the twin tracks merge — under the all-seeing eye of God. It is here that justice, as defined by the will of the Creator and revealed in his Word, comes to bear upon the economy.”

Lemonis is an “economic artist” in this area, and he bears the unique burden of executive stewardship with remarkable care and discernment.

3. Selfishness Kills; Service Prospers

As is already evident in numbers 1 and 2, the show demonstrates, more broadly, that basic ethics and attitudes matter if a business is going to be successful. This plays out in numerous human decisions, interactions, and relationships, and the virtues and vices vary. But in general, each episode reminds us that, contrary to the popular Gordon Gekko caricatures, in business as in the rest of life, greed and selfishness kill and service and sacrifice prosper. The first shall be last, and so on.

Greed and selfishness are not features of economic action; they are features of human nature. Although they may at times be funneled to achieve temporary and personal gain, more often they prove damaging and poisonous to long-term economic success. In most of the failing companies on “The Profit,” it becomes clear quite quickly that greed and selfishness are primary drivers of the failure. Many of these entrepreneurs have gone to great lengths to stroke their own egos and self-affirm their illogical designs, even when all signs tell them to stop. Blind idolatry to human desire is, in fact, the most dangerous poverty trap.

With Swanson’s Fish Market, the deal (and thus, the business) goes rapidly downhill when the owners refuse to give up their prized BMW and boat, even though they’re so financially strained that their own employees aren’t getting paid. With Worldwide Trailers, financial losses mount each year because one owner prefers a particular house in a particular posh city that only makes sense for her and her selfish preferences. With Skullduggery, a toy manufacturer, the owners’ arrogance and incompetence is embarrassingly clear, yet, even when given chance after chance, they drift back to their self-destructive habits and ideas, and in the end, even manage to exploit Lemonis for personal gain.

Perhaps the best example of this lesson is in the episode on Michael Sena’s Pro-Fit (now renamed Tina and Michael Sena’s Pro-Fit, for related reasons), wherein the owner, a self-absorbed trainer, can’t see beyond his self-image and ego and the damage it does to his business and marriage.

Thankfully, he’s one of the select people who decides to make a drastic change, and his transformation by the end of the episode shows what a difference that shift in basic attitude and orientation can make. This ends up not only being good for the Senas’s business, but for their marriage, their community, and everything in between.

Like each of these lessons, the situation is not unique to them or their business, yet they and many others have struggled to see that service and sacrifice, and more importantly, properly ordered love, need to be at the heart of our stewardship. Thanks to Lemonis, these business owners, and CNBC, that message is getting a great boost.