Thirty years ago today, Marian Anderson died while staying with her nephew in Portland, Oregon. Once one of the most influential African American figures in the U.S., Anderson changed the heart of our nation and our children.

Almost any child who has gone to Sunday School or Vacation Bible School in the past 50 years has sung the toe-tapping, hand-clapping “He’s Got the Whole World in His Hands,” complete with arm movements.

While the verses may vary, the song tells of the Almighty God who has the wind and rain, the moon and the stars, the little bitty baby, you and me, sister and brother, and the whole world in His hands.

While often introduced as a children’s song — even included in the “children” section of some hymnals — it is actually an old African American spiritual, shared through oral tradition in the rural South for years. It didn’t appear in print until 1927 in a book of folk songs, “Spirituals Triumphant, Old and New,” collected by African American singer and composer Edward Boatner.

After its publication, “He’s Got the Whole World in His Hands” found its way to one of the most brilliant singers of the day, the renowned contralto Marian Anderson, with a voice Italian conductor Arturo Toscanini said, “only comes along once in a hundred years.” Deeply religious and moved by the spiritual’s message, Anderson added it to her repertoire, along with her other favorites like Franz Schubert’s “Ave Maria,” Gaetano Donizetti’s “La Favorite,” and J.S. Bach’s “Komm, Süsser Tod.”

In her 1957 autobiography, “My Lord What a Morning,” Anderson wrote, “I chose it because it had a cry, an appeal, a meaning to me. It is more, much more than a number on a concert program.”

In her deep, soulful voice, Anderson’s performance of the spiritual became a testimony of her faith in an all-powerful God who excludes no one and holds “everybody” in His hands. This song reflects Job’s words to his friends, when he says in Job 12:10, “In His hand is the life of every living thing and the breath of every human being.”

It is a message replete with the stated equality and human dignity of every person — the little bitty baby, the brother, the sister, and everybody — before God. It was a powerful rebuke of the punishing Jim Crow laws of segregation, discrimination, and prejudice that had closed many venues, hotels, restaurants, and even restrooms to the African American singer despite her many successes overseas.

Surely the message was fitting for the day of the March on Washington on Aug. 28, 1963, when Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. gave his powerful “I Have A Dream” speech. Anderson, whose faith, fortitude, and exceptional talent had inspired Dr. King from his childhood, stood before the integrated audience of 250,000 people and sang, “He’s Got the Whole World in His Hands.”

Early Life

Marian Anderson was born Feb. 27, 1897, in Philadelphia, the oldest of three girls. Her family had moved to the city from Virginia for better opportunities, escaping the society where all four of her grandparents had descended from enslaved families.

The Andersons faithfully attended Union Baptist Church, where Marian’s love of music and her gift of song was discovered early. She was only 6 when she began singing in the choir, where she learned music quickly and could sing soprano, bass, alto, and tenor parts to fill in wherever was necessary. She sang solos at local churches and community groups, earning money to help support her family because her father had died in a work-related accident when she was just 12.

After the Philadelphia Music Academy refused her admission because of her race, she was introduced to Italian voice master Giuseppe Boghetti, who was so impressed by her talent (he wept when she sang “Deep River”) that he gave her free lessons for a year. In 1925, she won a contest to sing at Lewisohn Stadium with the New York Philharmonic. Winning contests and scholarships and gaining maturity in her singing, she eventually went on her first — of many — European tours in 1930, where she won acclaim from conductors, kings, and audiences for her deep, powerful voice.

She sang for the great Finnish composer Jean Sibelius in his home. He told her that her performance of “My Roof Is Too Low For You” was so inspired, he dedicated the song “Solitude” to her.

Despite her international fame, Anderson continued to face closed doors. After singing at McCarter Theatre, a concert hall in Princeton, she was denied a room in Princeton’s Nassau Inn, which held a whites-only policy. When audience member Dr. Albert Einstein heard of her rejection from the inn, he invited the singer to his home and began their long friendship.

Dramatic Career

But perhaps the most dramatic moment of her career came during the U.S. concert tour in 1939. In scheduling a concert in Washington, D.C., the sponsors chose the most popular and fitting venue: Constitution Hall. But the Daughters of the American Revolution, who owned the building, refused to let her sing because of her skin color.

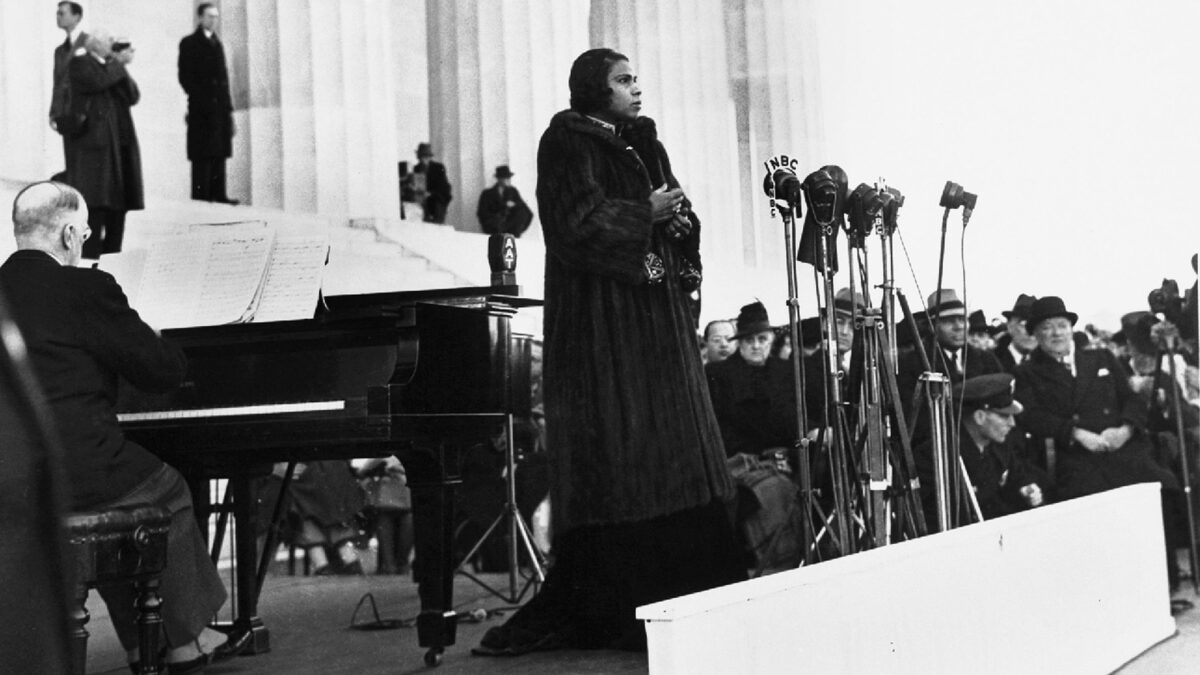

The resulting uproar — which saw President Roosevelt’s wife Eleanor publicly resign from the DAR — led to the famous Easter Sunday 1939 concert at the Lincoln Memorial. More than 75,000 people attended, with a broadcast radio audience as well, and it was the first major integrated gathering in the nation’s capital.

Introduced with the phrase “genius knows no color lines,” Anderson opened her concert with a stirring “My Country, ‘Tis of Thee,” followed by arias and art songs and ending with spirituals.

Listening by radio to her historic performance was 10-year-old Martin Luther King Jr., and the memory of that momentous day inspired him to choose the Lincoln Memorial for the 1963 civil rights March on Washington, where Anderson sang again.

In the face of ugly racism, Anderson achieved many African American “firsts.” She was the first to sing in the White House and at presidential inaugurations, the first to perform in Constitution Hall, and, in 1955, the first to perform with the New York Metropolitan Opera, performing the role of Ulrica in Verdi’s “Un Ballo In Maschera.”

Faith in the God Who Holds the World

With an anchored faith and a deep, life-long love of music, Anderson sang to mesmerized audiences throughout the world. Performing in the U.S., Europe, and South America, she continued her world tour in 1957 as a U.S. State Department’s goodwill ambassador in Israel, the South Pacific, and Asia.

Her programs often included her most precious spiritual, “He’s Got the Whole World in His Hands,” which she sang reverently and passionately. Throughout the whole world, Anderson held audiences in her hands with her magnificent voice. Anderson’s performance of “He’s Got the Whole World in His Hands” was selected for the Library of Congress’s National Registry in 2003 and inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame in 2008.

Her nephew, famous orchestral conductor James DePreist, wrote about his aunt in a 2002 introduction to her autobiography:

When I think of the qualities most often associated with Marian Anderson, humility comes first to mind, humility anchored in faith and gratitude for her gifts. Arrogance was inconceivable. My aunt never felt that her successes were hers alone, rather they were primarily God’s doing. ‘My part in it is very small indeed,’ she would say.

Throughout her life, she never lost sight of the fact that there is a great, big God who holds Marian Anderson and the whole world in His hands.