Extolling the virtues of a quality education system may seem like stating the obvious, but in countries like the United States, this needs to be reiterated repeatedly, since it’s easy to become discouraged with efforts to reform education. For more than a century, federal, state, and local governments have devoted so much time and money to improving schools. Indeed, the American government spends far more on public education than most countries in the developed world.

However, despite this, the American education system remains rather lackluster. Not only do American students rank below many other countries in the world, but it has largely failed in closing the achievement gap between students. Whatever people are trying to do in American schools, it’s evidently not working.

Naturally, this gives people reason to doubt the whole endeavor altogether. After all, what if it’s all one big mistake to expect so much from public schools in the first place? What if students will simply follow their predestined path no matter what their schools do? Could all the extra money used for education be put to better use?

This is the argument of a recent essay by writer Freddie deBoer, who no doubt echoes the thoughts of many burned-out teachers. He claims conversations about education have been distorted by “optimism bias, the insistence that all problems in education are solvable and that we can fix them if only we want to badly enough.” He notes most empirical data show nearly all students will group themselves into certain academic tracks based on inherent ability, regardless of the educational setup. Nevertheless, education reformers insist on continually changing the setup and applying a growing array of interventions to improve public education for all students.

Many Gimmicks Have Been Tried

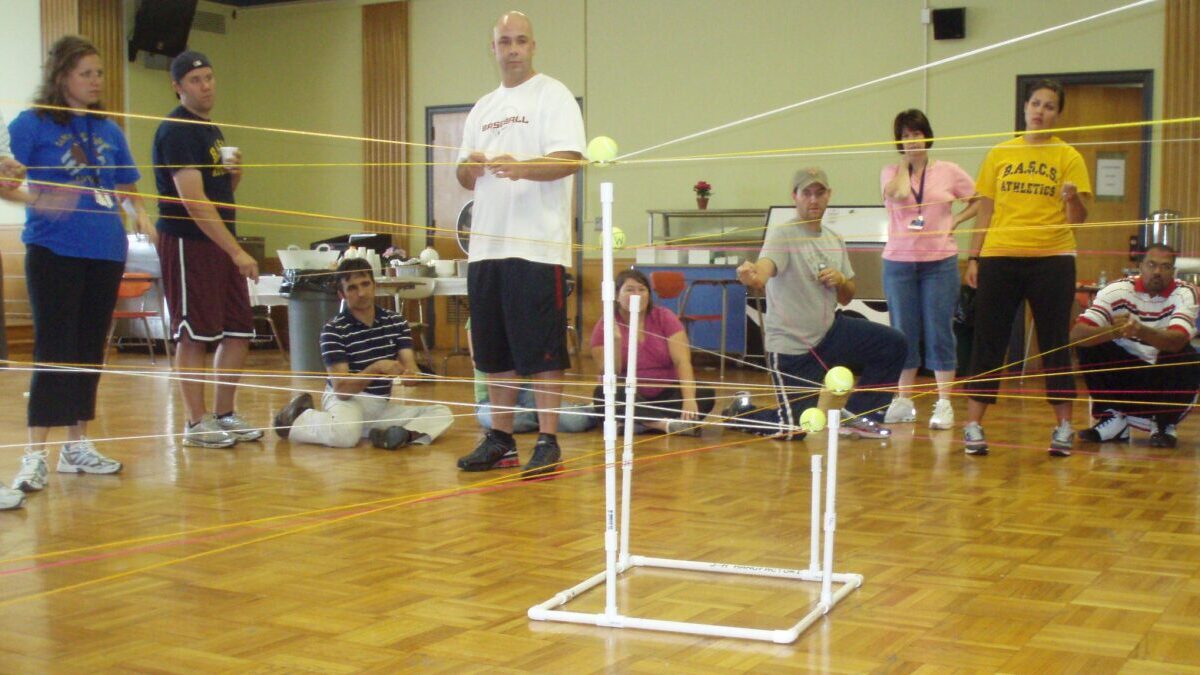

As a teacher myself, I actually agree with much of what deBoer is saying. For as long as I can remember, there has been a continuous cycle of interventions (I tend to think of them as “gimmicks”) to boost performance while achieving some level of equal academic outcome. To name just a few, I’ve observed districts focusing on testing and being “data-driven,” hyping technology and learning software, pushing student engagement above all else, demanding all instruction be project-based, altering grading systems, and incorporating restorative justice for student misbehavior.

And sure enough, all of these gimmicks require trainings, materials, curriculum, offices, and employees, all of which cost large sums of money. But for all this, I’ve never seen any of the gimmicks actually improve the quality of education — on the contrary, they usually make it worse.

Clearly, deBoer is right to suggest that simply spending more money on yet more gimmicks will not do anything. However, this is exactly what leftist educators and politicians want to do. NPR education correspondent Anya Kamenetz exemplifies this logic in her book “Stolen Year.” After doing much research and conducting many interviews with people who suffered from school shutdowns during Covid-19, the only solution she can come up with is increasing funding for schools.

Wrongly Dismissing School Choice

However, deBoer’s argument goes off track when he conflates educational gimmicks that have been tried for decades with the school-choice proposals. After condemning the projects of leftist educrats, he quickly dismisses the ideas behind charter schools, school vouchers, and merit pay: “the teacher merit pay research is a mess, private school vouchers have a deeply discouraging research record, and whatever positive results charter schools have seen are very small compared to the hype and questionable thanks to non-random distribution.”

There are a couple of problems with this criticism. First, the differences between the gimmicks I’ve witnessed and the policies he’s criticizing are a difference in kind, not degree. Therefore, it’s wrong to put them in the same discussion. If a certain merit pay system or charter school fails, this is for a completely different reason than a social-emotional learning (SEL) program not fixing bullying.

Second, many school-choice policies are relatively new, making them difficult to judge. Most charter schools are only a few years old, having opened after states and cities changed their laws. Most wide-scale school-choice initiatives, like those in Arizona or Florida, have only been implemented in the past year. Unlike the data that exists for standardized testing or various pedagogical methods, there’s little to go on when evaluating these other innovations. They may all fail, as deBoer and his supporters seem to think, or they may prove to be real game changers, as I’ve come to believe.

There’s reason to think having more charters would revolutionize education and put far more pressure on public schools to improve. In a recent article in the New York Post, most research that exists indicates charters do better than district-run schools, asking more from students and taking more action to ensure safety and order on their campuses. This is not just the case in New York City but in most urban districts. Even here in my north Texas suburb, I send my child to a classical charter school because it’s more academically rigorous, prohibits technology, and is much safer than the public schools nearby, even though they have a good reputation.

A person like deBoer may attribute this to charter schools having the freedom to pick and choose students, whereas district schools are forced to take in all students. It’s a fair point, but it’s ultimately an excuse for inaction. If public schools are held back by bad students, they should devise a system that neutralizes their effect on the classroom — like creating additional tracks for struggling students or letting them learn remotely.

Overly Pessimistic

More generally, deBoer’s argument falls flat in his conclusions. Since nothing seems to work and everyone’s high on hopium, he seeks to insert some much-warranted pessimism into the conversation: “someone has to point out that the history of modern American education gives us every reason to be pessimistic, as time after time, hype has given way to sad reality.”

Presumably, this anti-hype man would steer all attempts at societal improvement away from education and toward various welfare and universal basic income programs that deBoer somehow believes will be more effective: “Why hang our hopes on eradicating poverty and racial inequality on the entirely unproven mechanism of education when we could just give people money?” he asks.

I think most of us would welcome more realism in considering what’s possible in education and what is not, but deBoer’s brand of pessimism is utterly misguided. It mistakes the forest for the trees, casting ineffective educational gimmicks and failed programs as proof that the overall quality of one’s schooling has no effect on an individual’s success. Worse still, by tying academic achievement to inherent ability (nature over nurture), his argument implies the only real way to make a population smarter is through eugenic methods. And no, recommending that the government cut more checks to the poor doesn’t make this argument any less racist or classist.

Rather than succumb to despair, we should redouble our efforts in reforming our country’s education system, which obviously stands in great need of it. Although it may not be feasible to cultivate a nation of hyper-intelligent intellectuals or to create a system of perfect academic parity between each and every subgroup in the population, there are many ways to go about improving the system.

In general, we should play to our culture’s strengths by developing a system that is freer, more competitive, more practical, and more pluralistic (i.e., offering different paths of success) — all of which become more plausible when the gimmicks are dropped and school-choice policies are expanded. In some ways, this is already happening in various classrooms and campuses if we’re willing to look around. The worst thing we could do is give up, admit defeat, and sentence our children and civilization to a darker future of ignorance and mediocrity because nothing seemed to work like we thought it would.