The new TV series “Severance” on Apple TV has many things going for it. It has a great premise, a great cast, and an experienced crew of writers, directors, and producers. The show takes place in the near future (or alternate present?), where a large company has developed a way to sever employees’ minds into two. It examines the implications this has for a handful of office employees who have undergone the procedure.

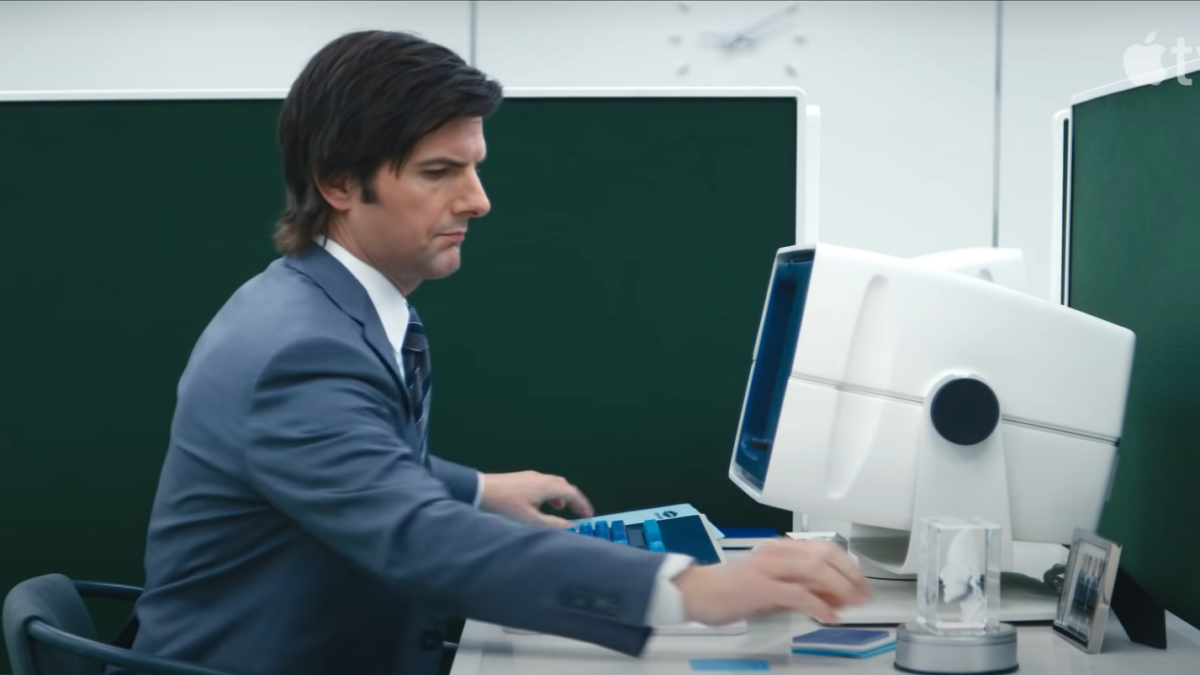

Considering that the cast features comic actors like Adam Scott, Christopher Walken, and John Turturro, and that Ben Stiller is one of the producers and directors of the show, one might expect some kind of satire. Perhaps it would expose the dehumanizing meaninglessness of office work, or the self-objectification that the modern world conditions in people, or how an environment affects an individual’s personality. Sure, there might be some heavier moments, but the overall tone would be comedic.

Unfortunately, “Severance” annoyingly flouts all expectations and wallows in ambiguity. It isn’t really clear what it’s trying to say until the second half of the season. In the first half, it could be making a subtle commentary about today’s culture or serve as an allegory for something, but so little is revealed that it’s impossible to say.

Coupled with this is the dark yet quirky style of the series. It’s less like “The Office” and more like “Twin Peaks.” While much of each episode’s plot is serious and hints at something diabolical, it’s also punctuated by humorous moments of absurdity. There are also disturbing dream sequences to further disorient the audience.

‘Severance’ Struggles to Decide What It’s Trying to Do

This odd combination is showcased in the first episode, which begins with one of the main characters. Helly (played by Britt Lower) waking up on a boardroom table answering questions from an intercom. It becomes apparent that her mind was severed and thus she can’t remember anything about her life. All the while, her colleague Mark (played by Adam Scott) is trying to acclimate her to do work that no one, including himself, actually understands.

Slowly but surely, the series begins to answer questions about what’s happening. These people are “data refiners.” Even if they hate this work — and most of them do — they cannot leave. Their drudgery is completely unknown to their outer selves (“outies”), who continue to report to work each day, bringing their inside selves (“innies”) back to consciousness. Ongoing compliance is incentivized with baubles and little celebrations while noncompliance is punished with trips to “the break room.”

However, for every question an episode might answer, 10 more come up. Throughout the season, it remains unclear where and when the story takes place, what Lumon Industries actually produces or how big it is, who the characters really are, or why or how anyone does what they do.

While a little ambiguity can help build tension and draws in the audience, too much of it prevents any kind of investment in the story or its characters. Thus, it’s hard to make any judgments or come to any conclusions about anything in “Severance.”

The series also has a problem with straddling genres, which can be confusing and irritating. At times, “Severance” is a drama about broken people; other times, it’s a dark comedy of workers making the best of an abysmal situation; and then sometimes, it’s a thriller where people go missing and conspiracies are hatched. In trying to be all things to all people, it becomes a mess of unrealized ideas without a coherent identity.

This mixup of genres affects the show’s pacing, which is uneven and frustratingly slow at times. One gets the feeling the writers are still trying to figure out how much exposition they want to reveal and what tone they want to set.

A Perfect Opportunity to Critique Our Technocracy

Fortunately, by the second half of the season, the pace picks up as some conflicts and ensuing developments actually materialize. At least in this regard, some themes that one expects to see do begin to emerge — mainly in the way the modern workplace atomizes individuals and overrides their wills.

Not only are the severed employees kept in the dark about their outer selves, they are kept in the dark about nearly everything. They know nothing about other departments, other parts of the building, or even what kind of work they do. Their situation seems more like a social science experiment than actual work. At the point they begin realizing this, the characters start taking noteworthy action.

This is also when the show begins to mirror the conflicts of real workers in today’s “knowledge economy,” which has a tendency to feed unsuspecting souls into a nihilistic grinder, causing them to lose all sense of themselves and become deeply unhappy. Many scenes in the later episodes of “Severance” tie into the claims made by Matthew Crawford in his excellent essay, “The Case for Working With Your Hands.”

In it, Crawford goes into excruciating detail about the special kind of hell of today’s offices. The work is pointless, there is no community, and lots of people are depressed. Much of this is encapsulated in Crawford’s recollection of his former colleague, Mike, who helped write abstracts at a think tank: “Always funny and gentle, Mike confided one day that he was doing quite a bit of heroin. On the job. This actually made some sense.” So too does it start making sense when the characters in “Severance” begin increasingly desperate measures to learn more about their jobs and find some source of meaning.

It should also be added that the cast does an amazing job, making otherwise bleak and uninteresting characters likable and deep. Adam Scott shows impressive range as an embittered widower who nonetheless does his best to regain some kind of personal stability. His boss Harmony Cobel is ably played by Patricia Arquette, who ends up being a surprisingly sympathetic antagonist. Other standout performances are from Tramell Tillman as the friendly yet sinister supervisor Milchick, and Michael Chernus as the brother-in-law Ricken who styles himself as a self-help guru.

Moreover, there are some intriguing revelations towards the end of the season that would make for a better story in the following seasons. It still remains open what path the show will take, but now there is a discernible path.

That said, making it through the first season will require some patience. It cannot be said that “Severance” squanders the potential so much as it leaves so much of its potential untouched. Hopefully, the creators of the series will finally make up their minds in the second season and take advantage of the foundation they’ve set.