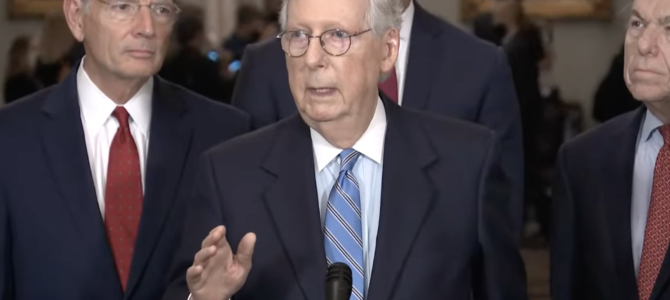

In July, Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., pledged “a hell of a fight” to stop Democrats’ $3.5 trillion spending blowout, which “is not going to be done on a bipartisan basis.” That “fight” lasted for less than three months.

On Wednesday, McConnell began negotiating an agreement with Minority Leader Chuck Schumer, D-N.Y., to raise the debt limit until some point in December. McConnell’s offer also attempted to force Democrats to use the budget reconciliation process to pass a longer-term debt limit increase, but Democrats quickly rejected that element of his proposal out of hand.

As part of this agreement, McConnell got Democrats to vote to increase the debt limit by a specific amount (i.e., authorize so many billions or trillions in new borrowing), rather than suspend it to a certain time (i.e., suspend the debt limit until December 16, 2022, as Democrats originally proposed). Some may consider this a meaningful concession, one that more readily allows for political attack ads, but in reality, anyone who votes to suspend the debt limit votes for all the debt incurred during that period of time regardless.

In exchange, McConnell 1) got no policy concessions at all; 2) gave Democrats the time and space to ram through their massive spending bill; and 3) created the reasonable expectation that Republicans will cave on the debt limit a second time when it comes up in December. (Congressional leaders will probably try to cram that debt limit increase into an omnibus spending bill totaling thousands of pages.)

Just as important, McConnell violated the letter that he and 45 other Senate Republicans signed on August 10, when they said that “We will not vote to increase the debt ceiling, whether that increase comes through a stand-alone bill, a continuing resolution, or any other vehicle.” McConnell and several of his colleagues will now have to vote to help the Democrats pass a debt limit increase, which they said two months ago they would not do.

This isn’t savvy legislating; it’s an all-out surrender, and one the Biden administration was publicly banking on all along. Generally, when both Democrats and Republicans think you caved — one GOP senator said “you could hear a pin drop” when McConnell explained his debt limit offer to his Republican colleagues — that’s exactly what you did.

Republicans Had Leverage…

It’s worth dispensing with the main McConnell talking point about the debt limit: that Democrats had all the votes they needed to raise the debt limit unilaterally. That was true at first, but Democrats surrendered that advantage more than six weeks ago when the House formally adopted Senate Democrats’ budget resolution on August 24.

Once the House and Senate agreed to a concurrent budget resolution — one that did not provide for a debt limit increase via budget reconciliation — they gave control of the issue to Republicans. For the uninitiated, the reconciliation process, which has strict parameters, allows the Senate to pass fiscal matters with a simple majority of 51 votes (in this case, 50 Democrats plus Vice President Kamala Harris), rather than the 60 votes normally needed to break a filibuster.

Guidance issued by the Senate parliamentarian earlier this spring permitted Democrats to revise that budget, to allow for a debt limit increase to pass on a party-line basis via reconciliation. But amending the budget first requires a vote in committee — and that committee process requires Republican cooperation.

Senate rules require a majority of committee members to be physically present for any committee markup. But the 50-50 divide in the Senate this Congress led party leaders to split committee assignments evenly between Republicans and Democrats, giving neither party a majority. If all Republicans boycotted a Budget Committee markup, Democrats would have no quorum necessary to report their revised budget — and therefore no ability to increase the debt limit via reconciliation.

… And Now Have Complicity

While the general public might not have understood the procedural details, McConnell’s team knew since mid-August that raising the debt limit would require Republican cooperation to smooth the reconciliation process along, if not Republican votes. And what policy concessions did McConnell request, knowing that his party would have to bear at least some of the political burden of the debt limit increase? As McConnell himself wrote to the president on Monday, “We have no list of demands.”

McConnell’s only “ask,” if one can call it that, was that Democrats use the reconciliation process to raise the debt limit, attempting to force Democrats to use a more circuitous route that involved additional Senate votes. That didn’t amount to a substantive policy request as much an attempt to play “gotcha” politics.

I wrote several weeks ago that a vote to raise the debt limit amounted to a vote for Biden’s $3.5 trillion tax-and-spend monstrosity. And Senate Republicans knew full well the link between the two issues. Here are a few examples.

Minority Whip John Thune, R-S.D., said, “A lot of our members are very uncomfortable doing anything that would make it easier” for Democrats to raise the debt limit.

Sen. Mitt Romney, R-Utah, who serves on the Budget Committee: “Republicans are not going to want to vote procedurally to [raise the debt limit] because then we become complicit and that’s not something we want to do.”

Sen. Susan Collins, R-Maine: “Some Republicans would vote to raise the debt limit if they knew the Democrats were going to abandon the $3.5 trillion package.”

After McConnell’s surrender, Democrats recognized the same dynamic — that Republicans caving on the debt ceiling paved the way for them to focus the rest of the fall on their tax-and-spending spree:

[Sen. Tammy] Baldwin, D-Wis., argued that the deal will allow Democrats to avoid wasting weeks of floor time on raising the debt ceiling under the reconciliation process when they would prefer to be working on a reconciliation package to implement President Biden’s $3.5 trillion Build Back Better agenda.

“I believe that Mitch McConnell is trying to steer [us] into this reconciliation process because it takes away from the main Biden Build Back Better agenda,” she said. “We intend to take this temporary victory and then try to work with the Republicans to do this on a longer-term basis.”

“McConnell caved,” Sen. Elizabeth Warren, D-Mass., declared after the [Democratic] caucus meeting. “And now we’re going to spend our time doing child care, health care, and fighting climate change.”

So much for “a hell of a fight” to stop the spending blowout.

‘Nuclear’ Threat Prompted a Cave

McConnell’s surrender came mere hours after Biden and other Democrats signaled a willingness to re-examine the Senate filibuster if the debt limit standoff continued. Biden’s comments Tuesday represented a 180 from his position as recently as last week — a remarkably quick flip-flop, even by his standards.

Likely the McConnell camp believes that he had to pursue this tactical retreat, lest Democrats deploy this “nuclear” option to destroy the filibuster, which would open the way to other harmful legislation. But that claim belies the fact that even after Biden’s comments Tuesday, “operatives within the [Democratic] party are skeptical that senators will ultimately scrap the filibuster rules at this moment.”

Moreover, Sen. Joe Manchin, D-W.V., said on Wednesday he opposed changing the filibuster rule to resolve the debt limit standoff. Politico reports that Manchin’s public comments came after McConnell called Manchin, giving him advance notice of the former’s debt limit offer — a fact likely leaked by the McConnell office, to advance the narrative that McConnell’s offer prevented Democrats from going “nuclear.”

But given that on Monday, Manchin said that “The filibuster has nothing to do with [the] debt ceiling” and that “we have other tools [i.e., reconciliation] that we can use and if we have to use them we should use them.” Manchin seemed unlikely to cross the filibuster rubicon on this issue irrespective of McConnell’s gambit, meaning the latter surrendered both unilaterally and unnecessarily.

Regardless, McConnell knew or should have expected earlier this summer that a debt limit standoff could precipitate a further showdown regarding the filibuster. If he didn’t want to fight that battle, he shouldn’t have started it in the first place. But he did, and he caved. Now, Democrats will have every reason to expect him to cave again come December.

Ordinary citizens hate Washington politicians because they talk a big game and rarely if ever deliver. That’s exactly what conservatives expecting an actual fight from Mitch McConnell over the spending binge got: another “all hat and no cattle” moment. If Democrats do end up passing their tax-and-spend legislation later this year, conservatives should remember that this moment and Mitch McConnell helped bring it about.