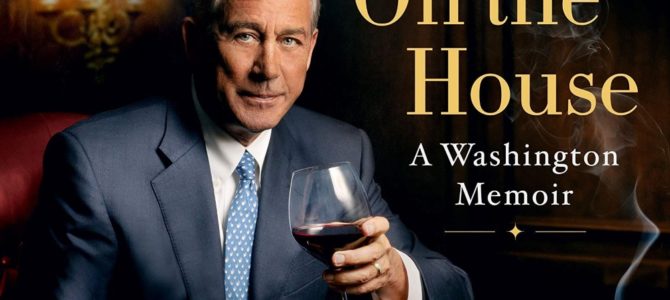

According to former Speaker of the House John Boehner, everything in the Republican Party would be going swimmingly if everyone had just listened to him: Barack Obama, George W. Bush, John McCain, Harry Reid, the “knuckleheads” and “legislative terrorists” on his team. Even “Lucifer in the flesh” Ted Cruz. The thread that connects all of them is their failure to not greedily gulp Boehner’s pearls of wisdom.

Everyone is the hero of their own memoir, and Boehner certainly is in his. Yet in recounting his path to power — and evolution from bomb-thrower to embodiment of the establishment — he fails to reckon with his role in bringing to bear the “legislative terrorism” he so graphically (and profanely) decries.

The country changed under Boehner’s watch, and organic political movements like the Tea Party rose in response to it. History — and the end to Boehner’s career as speaker — demonstrate how badly he misread the moment, largely by failing to take seriously both the concerns and the urgency expressed by a significant segment of Republican voters.

The differing factions that arose in the Republican Party — factions that still exist to this day — needed a leader with the self-confidence and courage to evolve both the party and the political process in a way that allowed voters to be heard. Instead of that story, however, we witness a man whose country and political landscape change while he’s stubbornly determined not to notice — one who grips the reins tightly and presides over the era of passive nothingness that leads a fed-up Republican base to send Donald Trump to the White House in 2016.

Rather than writing a book that engages in even a passing attempt at self-reflection on this point, however, Boehner descends into a litany of bitter commentary; a man desperately determined to prove how right he is by angrily insisting everyone else is a lunatic. One pictures him with a lit Camel gripped in a rage-clenched jaw, sloshing his tenth glass of Merlot onto the keyboard as he furiously denounces Mick Mulvaney, Mark Meadows, Tim Huelskamp, Jim DeMint, Mike Lee, and, of course, the villainous Ted Cruz.

In Boehner’s telling, it was the unbending Republican “demagogues” and “hard right hardliners” on immigration — like Rep. Bob Goodlatte — who tanked the 2013 immigration reform bill instead of the bill’s amnesty provision, questionable border security measures, and giant giveaway to the Chamber of Commerce for cheap foreign labor, none of which merit his mention.

While expressing justifiable outrage at the partisan way Obamacare was shoved down the throats of Americans, Boehner aims his rage against GOP members who led the 2013 government shutdown in a last-ditch attempt to leverage raising the country’s debt ceiling for the law’s repeal or significant reform.

Boehner doesn’t understand why Republican voters weren’t happy with his efforts. Thanks to him, “there isn’t really much of Obamacare left,” he says (after all, he muscled through a repeal of Obamacare’s medical device tax). America’s biggest device manufacturing companies will no longer have to pay a 2.3 percent tax. Why is everyone still complaining?

What Remains Unsaid

What makes the book most interesting, however, are the topics Boehner chooses not to fully address. Several parts of the book reference Boehner’s passion for fiscal restraint and responsibility and include more than a few lectures about the hypocrisy of the “crazy caucus” that claimed to be against government spending but did little to stop it during the Trump years.

Yet, curiously, the Budget Control Act — arguably the most significant win for conservatives on spending reductions in decades — makes no appearance in the book. Perhaps because Boehner was pushed into accomplishing it by the “jackasses” who populated “Crazytown.” Boehner also conveniently leaves out the fact he undid much of that signature spending achievement in 2015 as a way to “clean out the barn” for incoming House Speaker Paul Ryan, cutting a deal with President Obama that included erasing the caps on discretionary spending and hiking the defense budget.

It’s also notable that Boehner talks nothing about the circumstances under which he left the speakership, saying only that he felt “the presence of the Holy Spirit” during a visit by Pope Francis, which “gave me the idea to announce my retirement … the very next day.” With deference to the Holy Spirit, there is some key context left out of that discussion.

Namely, a motion to vacate the chair, filed by Rep. Mark Meadows right before the August recess in 2015, would have forced a referendum vote on Boehner’s leadership. Indeed, that motion was filed reflected the unhappiness that significant segments of the GOP felt with Boehner’s leadership, characterized by autocratic control over GOP House members.

Closed rules, which bar all amendments, had become the norm. Members were stripped of their committee positions for voting in opposition to their leadership. Key Obama priorities like Trade Promotion Authority were jammed through the House Republican majority with little input or say by the wider conference, while key conservative priorities like defunding Planned Parenthood were given only marginal consideration.

Throughout his memoir, Boehner called such decisions “getting things done,” made by “serious people” (like himself) who had to be “the adult[s] in the room.” Conservatives, on the other hand, called it a consolidation of power and centralized decision-making that “bypass[ed] the majority of the 435 members of Congress and the people they represent.” Rather than wait for the vote, Boehner stepped down.

A Paean for the Swamp

There’s no question Boehner was handed a complicated political moment. But it was a challenge to which he failed to rise, and appeared to confuse leadership with an obsessive need to do everything his way and on his terms. That said, his failure in that regard may have also been due to distraction. His memoir makes one thing abundantly clear: he really just wanted to be golfing.

In fact, he wanted to be doing a lot of things other than navigating the growing crisis and divide between the GOP’s elected leadership and the party’s base. Among them, hanging out with Lesley Stahl of “60 Minutes,” whose feature on Boehner gets several pages of effusive praise. Lobbyists get a whole chapter in their defense, perhaps because Boehner now is one, for the marijuana industry. Even reporters, he says, are largely harmless. Certainly not “the enemy of the people.” The deep state? That isn’t even real.

He misses hanging out with his friends on congressional delegations abroad, like the one where Libyan dictator Muammar Gaddafi gave Boehner his spare pair of sunglasses. Also, of course, the “Boehner Bus” trips for stateside travel, where a “fully loaded” bus was prepared for members to “relax, shoot the sh-t, watch TV, drink” (the only rule: No Girls Allowed).

As GOP voters were losing faith in the system and preparing to fire a nuclear missile across the bow in electing Trump, Boehner was in Hollywood having dinner with Clint Eastwood.

Boehner is right about one thing, however: earmarks, a practice he helped end. He returns to the subject twice in the book, characterizing his opposition to them not merely because of their contribution to discretionary spending, but to the role they play in entrenching corrupt power centers. How awkward it must be for him then, now that his beloved “grownups” in the Republican Party are intent on bringing back the practice, while the knuckleheads and cranks are the ones holding the principled line.

The memoir Boehner has produced does feature some genuinely charming anecdotes about growing up in Ohio with 11 brothers and sisters, working at his family’s bar, and his deep friendship with the late President Gerald Ford. But on the whole, it unintentionally makes clear that in a moment where the GOP needed courageous, visionary, and responsive leadership, Boehner was out to lunch. The book may be called “On the House,” but it’s most notable for its failure to read the room.