Nineteen-year-old Hosea Williams, an infantry gunner, was in a foxhole in France with 13 other soldiers when a German shell hit. Everyone was killed but Williams.

As staff sergeant in an all-black infantry unit attached to Gen. George S. Patton’s Third Army, Williams was one of more than 2.5 million African-American men who enlisted in segregated units and served with distinction and honor. Williams laid in that foxhole for two days with devastating injuries, until an ambulance could reach him. He spent 13 months in a veterans hospital and was discharged with a permanent limp.

After arriving in New York at the end of the war, Williams headed home to Georgia, dressed in full uniform, wearing his medals, including a Purple Heart. The bus stopped in Americus, Ga., and Williams was very thirsty. But it was 1945 in the segregated South, and blacks were not allowed in the bus station, not even decorated WWII soldiers. Williams didn’t like coffee, but he bought a cup, threw the coffee out, and tried to slide open the door just enough to fill his cup with water from the fountain.

A group of angry whites saw him at the “whites only” fountain and beat him so savagely they thought they had killed him and called a black funeral home to pick up the body. On the way, the hearse driver noticed Williams had a faint pulse and was barely breathing.

There were no hospitals in the area that would treat blacks, even in a medical emergency, so the driver took him to the nearest veterans’ hospital more than 100 miles away. Williams spent more than a month in the hospital recuperating from his injuries.

“I was deemed disabled by the military and required a cane to walk. My wounds had earned me a Purple Heart. The war had just ended and I was still in my uniform! But on my way home, to the brink of death, they beat me like a common dog. The very same people whose freedoms and liberties I had fought and suffered to secure in the horrors of war…they beat me like a dog…merely because I wanted a drink of water,” he said.

It was not the first time, nor the last, that Williams was the subject of white rage. At age 14, he had run away from home to keep from being lynched by a white mob because he went fishing with a poor white girl who lived near his grandparents. He was jailed more than 100 times in his quest for justice, once for 65 days, and was beaten countless times marching for freedom. But beaten, he didn’t break, forced down, he rose up, a crusader for his people, “unbought and unbossed.”

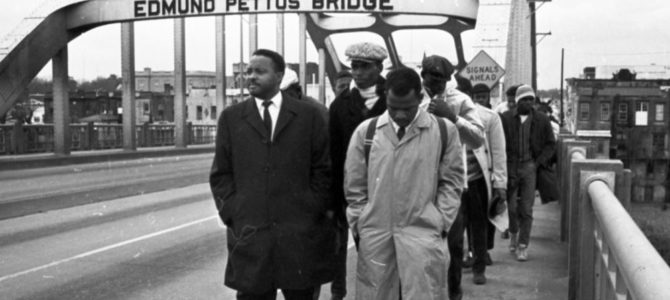

This March 7 marks the 56th anniversary of the “Bloody Sunday” voting rights march, when 600 peaceful marchers were met with violence at the foot of the Edmund Pettus Bridge. The march was led by Williams, representing the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), and John Lewis, with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee.

They had gotten special permission from Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. to hold the march. Lewis was elected to represent Georgia’s fifth congressional district in Congress in 1986, serving 33 years until his death in 2020.

“We crossed that bridge and there stood an army of 200 state troopers, possemen, and Sheriff’s deputies,” Williams remembered. In less than two minutes, the armed officers attacked the defenseless marchers. Marchers—mostly women and children—were beaten, whipped, and stomped on by officers; so much tear gas was shot into the crowd that you couldn’t see your hand in front of your face, Williams remembered. Sixty people went to the hospital for their injuries.

The carnage hit national television that night, showing uniformed officers beating men, women, and children who were wearing their Sunday best. ABC interrupted its Sunday night movie, “Judgment At Nuremberg” to show 15 minutes of the footage to an audience of 50 million. Many believe the juxtaposition of images of the Holocaust with the realities of the Jim Crow South helped create sympathy for the 1965 voting rights campaign, which led to the adoption of the Voting Rights Act in August of that year.

Foot soldiers from the movement, congressional delegates, and others from around the country come to Selma each year to commemorate Bloody Sunday with a weekend of events culminating in a symbolic march from Brown Chapel AME church across the infamous bridge. This year’s event will be virtual.

Lewis’s role in Bloody Sunday is well known. Often forgotten is Williams, who served as a field organizer for King in the SCLC.

Williams was born January 5, 1926 to blind teenagers who had met at the Georgia Academy for the Blind in Macon. His mother, 14, ran away when she found out she was pregnant and named her baby after her brother Hosea, who was also blind. His mother died when he was 10, and Williams grew up in Attapulgus, a small farming community in southwestern Georgia, with his maternal grandparents, Lela and Turner Williams.

Turner Williams was an illiterate farmer, but the “wisest man I have ever known,” Williams recalled, and his years in rural Georgia gave him a heart for the poor, those tenant farmers who worked from “cain’t to cain’t”—cannot see your hand in front of your face in the dark morning and then again at night—who were not allowed to plant tobacco because it was such a profitable cash crop, and were always put in debt by white landowners.

After the war, Williams completed high school at age 23, then earned college degrees in chemistry and physics, becoming the first African American research chemist with the U.S. Department of Agriculture Bureau of Entomology in the deep South, hired in 1952. He married Juanita Terry, a college professor, and together the couple raised seven children.

As a government employee, Williams was making good money and rising up the ranks as a hard worker who put in long hours. He enjoyed a comfortable life; he always bought the first Cadillac delivered to Savannah each year, lived in an upper-class neighborhood, and partied with his white coworkers in their homes.

One day, while taking care of his expensive Zoysia-sodded lawn, he took his two young sons, ages 6 and 8, to the store to get extensions for his garden hose. His children wanted to sit at the lunch counter and twirl on the stools like the other kids. But it was the early 1960s, and this was segregated Savannah.

“I had to tell them no, and I realized I couldn’t tell them the truth, that they were black and they didn’t allow black people at those lunch counters,” he remembered. “…I took them to the car and made a promise that I’d bring them back someday.”

That day motivated Williams to volunteer in the civil rights movement, joining the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People Savannah chapter. He gave speeches downtown during his lunch break, taught nonviolence, held voter registration drives, led sit-ins and marches and took many beatings.

The protests also sent him to jail for 65 days—the longest of any civil rights worker, and the first of more than 100 arrests in his journey for justice. The NAACP’s tenacity and determination eventually led to the integration of Savannah by 1963, eight months before the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Savannah became the first city in Georgia with desegregated lunch counters.

“I carried my boys to that lunch counter and we sat there and drank Co-colas and ate hot dogs and spun around on those stools,” he remembered. “I said, ‘It’s been a long time comin’, boys, so let’s enjoy it.’”

Williams’s impressive and fearless work organizing marches and getting results caught King’s attention, and Williams went to work for the SCLC in 1963, leaving his love for science for his greater heart for civil rights. Williams’ job with the SCLC was “to go into the community and break the fear that was binding blacks.” He was an inspirational speaker and got people excited about marching.

On April 4, 1968, Williams was one of the leaders with Dr. King at the Lorraine Hotel when he was assassinated. “I wondered had America lost its last chance?” Williams said in a television interview the day of the murder. “I couldn’t believe anyone was crazy enough to kill Dr. Martin Luther King, a man who wouldn’t hurt anybody but who loved everybody and gave his life for the salvation of this nation.”

Williams continued with SCLC off and on until 1979. His political career began in 1974 and continued through 1994; he was elected to the Georgia General Assembly, then served on the Atlanta City Council, and then the DeKalb County Commission, one of few Georgians ever to be elected to serve on the city, county, and state levels of government. Disappointed with politicians he believed too often sold out, Williams held fast to Dr. King’s words. “I truly believe we should never judge a person by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.”

Williams also remembered the poor, even wearing trademark denim bib overalls, when he established Hosea Feeds the Hungry and Homeless in 1971, now called Hosea Helps. It has distributed more than $3 billion in food, clothing, medical, educational, toiletries, furniture, and cleaning supplies to 16 Georgia counties, three states, and to the Philippines, the Ivory Coast, and Uganda.

“I had watched my best buddies tortured, murdered, and bodies blown to pieces,” he later recalled. “The French battlefields had literally been stained with my blood…Later I realized why God, time after time, had taken me to death’s door, then spared my life…to be a general in the war for human rights and personal dignity.”

Williams died in November 2000 after a three-year battle with cancer.

This article’s headline has been corrected.