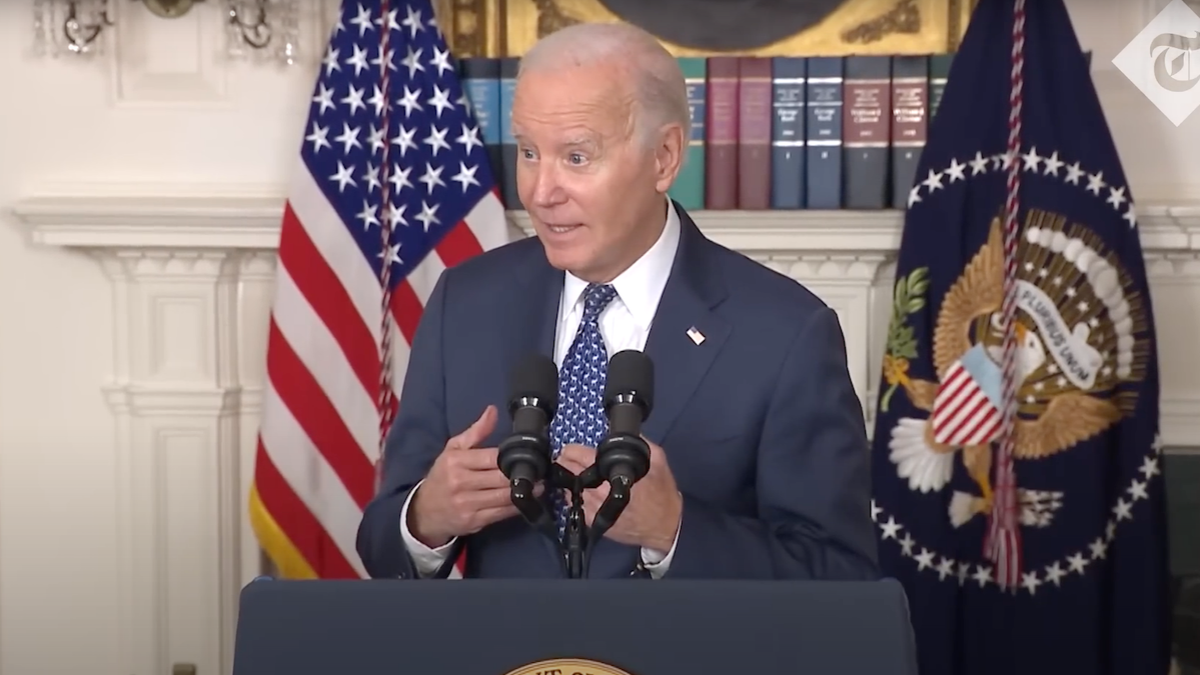

The last-minute impeachment of President Trump raises the question: can a federal officer be convicted by the Senate when he no longer holds office? We will soon find out the answer. While the House impeached Trump during his term, all indications suggest the Senate will not begin to even debate the matter until after he leaves office.

The Constitution grants broad discretion to Congress in this area. Article II, section 4 of the Constitution holds that the “President, Vice President and all civil officers of the United States, shall be removed from office on impeachment for, and conviction of, treason, bribery, or other high crimes and misdemeanors.” Historically, the definition of “high crimes and misdemeanors” has been very loose — essentially anything Congress wants.

In Federalist No. 65, Alexander Hamilton explained the prerequisites for impeachment:

Those offenses which proceed from the misconduct of public men, or, in other words, from the abuse or violation of some public trust. They are of a nature which may with peculiar propriety be denominated political, as they relate chiefly to injuries done immediately to the society itself.

James Madison was concerned that too broad a term would lead the president to serve “at the pleasure of the Senate,” but state ratification debates in 1787 and 1788 included assurances that Congress could impeach someone who “excites suspicion,” carries out “maladministration,” or even “those who behave amiss, or betray their public trust.” James Wilson, the legal scholar, and future Supreme Court justice, even suggested that a president could be impeached for “forming a bad treaty.”

The original public understanding of Congress’s impeachment powers thus show Congress has wide latitude on the subject matter, but what about the timing of an impeachment? There is less evidence of this debate in contemporary sources, but the general impression is that Congress’s power is similarly broad.

In a debate during the First Congress in 1789, Madison said a president “is impeachable for any crime or misdemeanor before the Senate, at all times.” The comment is some evidence, perhaps, that Madison may have thought the impeachment power not to have been limited by time.

The Impeachment of William Blount

The first attempt at impeachment adds to the case against a time limit as the person in question, William Blount, left office the day the House impeached him. But mixed up in this precedent was the fact that Blount was not what we would today think of as one of the “civil officers of the United States.” He was a senator.

In 1797, Blount had conspired to help Great Britain take control of Spanish lands to the west of the United States, believing that British ownership would better protect his investments in the region. Before the conspiracy could accomplish anything, Blount’s letters about the plot reached the Senate, which voted 25-1 to expel him.

Expulsion from Congress is not impeachment but a separate power found in Article I, section 5, which holds that “Each House may determine the Rules of its Proceedings, punish its Members for disorderly Behavior, and, with the Concurrence of two-thirds, expel a Member.”

The Senate’s action was, therefore, undoubtedly legal and constitutional, but the House, after limited debate, impeached Blount anyway. Rep. James Bayard of Delaware defended the post-expulsion impeachment:

If the impeachment were regular and maintainable when preferred, I apprehend no subsequent event … can vitiate or obstruct the proceeding. Otherwise, the party, by resignation or the commission of some offense which merited and occasioned his expulsion, might secure his impunity.

Blount protested that he was not a “civil officer,” and a majority of the Senate agreed to dismiss the charges on those grounds. They established an important precedent, but the issue of timing remained unsettled.

The Impeachment of William W. Belknap

The issue did not arise again until 1876, when the House impeached Secretary of War William W. Belknap. Belknap was one of several officials in Ulysses Grant’s administration who was accused of corruption and the House — controlled by Democrats for the first time since before the Civil War — was determined to root him out. Two hours before they were set to impeach, Belknap resigned, but the House proceeded against him anyway, voting to impeach after an hour’s debate.

This became the only time the issue of post-resignation impeachment was directly debated in the Senate. Montgomery Blair, Belknap’s lawyer, summed up the argument against impeachment:

All the reasons upon which the proceeding was supposed to be necessary applied only to a man who wielded at the moment the power of the Government, when only it was necessary to put in motion the great power of the people, as organized in the House of Representatives, to bring him to justice. It is a shocking abuse of power to direct so overwhelmingly a force against a private man.

For the other side of the argument, Rep. Scott Lord of New York said:

What is the real intent and meaning of the word ‘officer’ in the Constitution? It is but a general description. An officer in one sense never loses his office. He gets his title and he wears it forever, and an officer is under this liability for life; if he once takes office under the United States, if while in office and as an officer he commits acts which demand impeachment, be may be impeached even down … to the time that he takes his departure from this life.

With Belknap claiming that his resignation wiped out all grounds for impeachment and House Democrats claiming they could impeach him until he died, the Senate had a tough decision to make. What they came up with muddled: by a 37-29 vote, the Senate agreed that Belknap could still be impeached.

A majority supported the interpretation advanced by Lord and the other House managers, but with two-thirds needed to convict, they fell short. Belknap said the result “exonerates me as fully as if I had a thousand votes,” but the fact remains that most of the Senate thought the charges against him were still valid after he left office.

Disqualification from Future Office

Blair was correct that the main reason to impeach someone is to remove him from office. But it is not the only one. The Constitution’s Article I, section 3 says: “Judgment in cases of impeachment shall not extend further than to removal from office, and disqualification to hold and enjoy any office of honor, trust or profit under the United States” (emphasis added). Removal was no longer a factor for Blount or Belknap, just as it will not be for Trump on Jan. 20, but disqualification from office remains a punishment that the Senate may wish to impose.

In the Washington Post, Judge J. Michael Luttig suggests Congress’s desire to disqualify Trump does not override the implicit requirement that an impeached person holds office during his impeachment. In a reply to Luttig in the Post, Harvard Law’s Laurence H. Tribe disagreed, noting the Constitution’s silence on the question and Congress’s precedents in the Blount and Belknap impeachments. Historically, Congress’s opinion has been the only one that matters in impeachments.

Both answers have the potential to produce bad results. Belknap escaped punishment after his resignation, both when the Senate refused to convict him and when the government dropped bribery charges against him the following year. Indeed, Tribe points out the dangers of following Luttig’s interpretation:

To render this uniquely appropriate remedy unavailable simply because the gravest abuses of power were committed near the very end of a president’s term would be bizarre at best, self-sabotaging at worst. Nothing in the Constitution suggests that a president who has shown himself to be a deadly threat to our survival as a constitutional republic should be able to run out the clock on our ability to condemn his conduct and to ensure that it can never recur.

On the other hand, Scott Lord’s position that an officer may be impeached and convicted “even down to the time that he takes his departure from this life” seems excessive and cruel. Combine that with Wilson’s contention that a “bad treaty” is grounds for impeachment, and you could have Jimmy Carter impeached in 2021 for signing the Panama Canal Treaty in 1977. That is an absurd result, but mere absurdity has never stopped Congress before.

The right answer involves self-restraint. Someone who left office mere days ago may be a reasonable target for impeachment, especially if barring his return to office is Congress’s goal. The more time has elapsed, though, the more tenuous the claim to justice — whatever you think of the Canal Treaty, Carter should be allowed to enjoy his retirement.

Even in more recent cases, when a nation needs healing prosecution is often the wrong way to go about it. In 2016, Trump campaigned on the vow to “lock-up” Hillary Clinton; after his victory, the matter was quietly dropped. Self-restraint is increasingly unknown in our politics, but here even excessive zeal by the Democrats will not stretch the already loose constitutional boundaries of impeachment very far.

Like Belknap, Trump was impeached while in office and will be tried when out of it. Each Senator may consider that fact when deciding how to vote, just as they did in 1876 when Belknap was acquitted despite overwhelming evidence of his guilt. If they decide, this time, to convict, it will not undermine the Constitution any more than anything else that has happened this month. Whether it is prudent is for the Senate to decide.