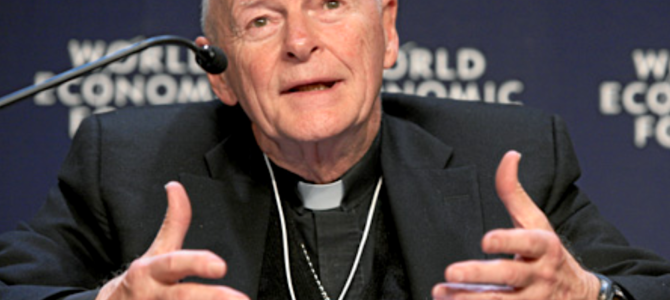

While the United States was reeling last week from an utterly chaotic election, the Vatican decided it was the right moment to publish its long-awaited report into disgraced former Cardinal Theodore McCarrick. The mammoth document is a nauseating account of clerical coverup, cowardice, and complicity that prioritizes subtle finger-pointing and deflection over real accountability. Those expecting an explanation of how a serially accused predator was catapulted through the church hierarchy despite serious allegations and rumors of assault and indecent behavior will be left not merely disappointed but disillusioned.

Equally unsatisfactory is its failure to disclose the extent to which this highly compromised man played a role in fostering relations between the Vatican and China and in helping to secure the controversial Sino-Vatican accord. While acknowledging that McCarrick made frequent trips to China over more than two decades and that his activities there, as in other countries, “constituted a form of soft diplomacy” for the Vatican, the report effectively brushes over McCarrick’s involvement in the eventual formal negotiations between the Holy See and China.

This confidential agreement has been a significant diplomatic win for China and a substantial loss for the country’s 12 million Chinese Catholics. It is also a slap in the face to protestant Christians and other religious groups, including Turkic Muslims in Xinjiang, where human rights violations rival those witnessed during Mao Zedong’s Cultural Revolution.

The so-called normalization of relations enables China to leverage Vatican soft power without putting forward any serious collateral. The public has a right to know what the church, and specifically Chinese Catholics, are gaining from the Vatican’s rapprochement with Beijing, and what McCarrick’s role was in bringing this to pass.

Church Leaders Enabled McCarrick

In 2018, McCarrick became the highest-ranking church figure in modern history to be expelled when allegations surfaced that he had sexually abused a minor during the 1970s. After a canonical process found McCarrick guilty of the two charges of “soliciting sex during confession” and committing “sins” with minors and adults “with the aggravating factor of the abuse of power,” McCarrick was defrocked and exiled to a Kansas friary.

At all levels of the church hierarchy, allegations of McCarrick’s depraved conduct were bounced around, perfunctorily investigated, and ultimately ignored. The report attributes the lion’s share of the blame to Pope John Paul II. The pontiff was informed of McCarrick’s misconduct, although not the full scope and nothing in relation to minors. Due to a combination of conflicting information, bad advice, and a gross misjudgment of McCarrick’s character, John Paul II took no action. McCarrick was instead rewarded with a promotion to Washington, D.C., and eventually a cardinal See.

Under Pope Benedict XVI, the fiasco was again mismanaged. When allegations resurfaced, and civil claims of abuse or harassment were privately settled, the cardinal was forced into early retirement. The Congregation for Bishops hashed out a plan, with the pope’s approval, to avoid a canonical process and instead “appeal to McCarrick’s conscience and ecclesial spirit” to refrain from travel, keep a low profile, and lead a “reserved life of prayer.” McCarrick was eventually able to weasel his way out of this nonbinding arrangement, apparently to the dismay of senior prelates who had foolishly relied on McCarrick to play the game.

Pope Francis was also aware of allegations and knew that the Congregation for Bishops had sought to handle the matter from 2006 by concluding that McCarrick should keep out of the spotlight. These recommendations notwithstanding, McCarrick continued to make his merry way around the world, informing Francis of his travels as he went. According to a 2014 Washington Post article, the prelate who had been “put out to pasture” during the pontificate of Benedict XVI was “back in the mix” under Francis and “busier than ever.”

How Much Influence Did the Vatican Give McCarrick?

Meanwhile, a disturbing question emerges amid the squalid and convoluted details: To what extent did the Vatican allow its diplomatic relations with China to be influenced by a consummate predator, a manipulative and ambitious powerbroker, and a pathological liar?

The inquiry’s terms of reference intentionally avoid providing “detailed information implicating foreign affairs, particularly as to ongoing or delicate matters.” The report is also careful to insist that “McCarrick was never a diplomatic agent of the Holy See” and was “never inside the negotiations undertaken” with China.

Yet McCarrick was greatly interested in what he called “the China project.” He made eight trips to China between 1992 and 2018 and liaised with successive U.S. administrations on matters of religious freedom, human rights, and the development of Vatican-Chinese relations.

Between 2003 and 2005, he met with Chinese Communist Party officials, members of the armed forces, religious leaders, priests, and professors. He met openly with leaders of the state-sanctioned Chinese Catholic Patriotic Association, but only “briefly and surreptitiously” with members of the underground church due to surveillance. He provided reports to Pope John Paul II and later Benedict XVI, and he briefed U.S. officials in Washington and at the U.S. Embassy in Beijing.

McCarrick described his role during this period as “very much involved in the China negotiations on behalf of the Holy See,” and resumed his visits to China under Pope Francis, renewing the call for rapprochement. McCarrick kept Holy See officials, especially Cardinal Pietro Parolin, secretary of state and Francis’s chief adviser on China, informed of his activities and contacts.

He would also meet with Francis and correspond with him regarding his progress. In 2015, he wrote to Francis, “With God’s help, before He calls me Home, I will help to bring you China.” For his part, Francis felt that McCarrick “could still do something useful,” as Cardinal Parolin recalls the pontiff saying in 2016.

A troubling question mark therefore arises over McCarrick’s role in shaping the eventual agreement between Rome and Beijing. The report betrays a distinct effort to distance the Holy See’s diplomatic efforts from McCarrick’s activities.

Despite this and McCarrick’s own contrived obsequiousness, he was not some washed-up cardinal left to his own devices to dodder around the world. He was highly connected, publicly active, self-promoting, and cunning. In its 2014 interview with McCarrick, the Washington Post summed it up as follows: “Francis, who has put the Vatican back on the geopolitical stage, knows that when he needs a ‘savvy back channel operator’ he can turn to McCarrick.”

Communist China Is Hostile to Religion

In 2018, after McCarrick’s fall from glory, the Holy See signed its provisional agreement with China. The church in China had for decades been split between the so-called underground church, in communion with the church in Rome, and the Chinese Catholic Patriotic Association, the bishops of which were state-appointed. The agreement ended the standoff over the appointment of bishops by recognizing those the regime had previously appointed and allowing Beijing the authority to propose the names of future bishops subject to the pope’s veto.

Meanwhile, religious persecution of Catholics and other religious groups intensified. Bishops and priests who refuse to register with the state and submit to the Chinese Catholic Patriotic Association are harassed, detained, imprisoned, and disappeared. Government regulations prohibit online evangelization, the open online publishing of catechetical materials, and online broadcasts of religious services, prayer, and preaching. Holy Scripture is reportedly being adulterated to bring ideologically inconvenient passages in line with socialist values.

Churches are routinely raided to force compliance with state regulations. In 2018, police shut down the unregistered protestant Early Rain Covenant Church in Chengdu and detained its pastor on charges of “inciting subversion.” In January this year, Wang Yi was sentenced to nine years in jail. The United Nations high commissioner for human rights found in 2018 that more than 1 million Uighur Muslims were interned in a network of concentration camps for re-education and forced labor.

CEO for Open Doors USA David Curry recently argued that the Vatican is being “played” by the Chinese, who are successfully repressing dissent and buying the pope’s silence. U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo has expressed similar concerns, having recently requested a meeting with the pope to discuss these matters before being lamely refused with the excuse of the pending U.S. elections. Human rights abuses notwithstanding, the Vatican went on to renew the accord last month.

Amid criticism, Cardinal Parolin has emphasized the “long road” toward normalization. When Pope Benedict XVI spoke of a lengthy reconciliation process and the need for a united Catholic Church in China, however, he was presumably calling for unity under the church in Rome, not subjugation of the faith to an atheistic, totalitarian regime and one of the world’s most notorious human rights violators.

Instead of calls to be “patient,” a useful contribution from Parolin and the Holy See would be a complete audit of the extent to which McCarrick’s murky fingerprints appear on any aspect of this sorry affair, including policy recommendations, diplomatic channels, and the eventual agreement itself. Such an inquiry would inevitably involve coming clean on the terms of the accord. In light of the disastrous human rights situation in China and continued persecution of Catholic faithful, as well as McCarrick’s dubious involvement, such a disclosure is essential.