Fifty-five years, 55 miles, and a 15-year-old girl with a Cracker Jack sole.

An old proverb posits that the shoemaker or cobbler’s child goes barefoot, as too often paying customers come before kin. It is a saying found in many languages and cultures. In Finnish, the saying is “suutarin lapsilla ei ole kenka,” or “the shoemaker’s children have no shoes,” and in Esperanto, it’s “ĉe botisto la ŝuo estas ĉiam kun truo,” or “in a shoemaker’s house, the shoe has always a hole.”

Somewhere along the 55-mile voting rights march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama, in 1965, 15-year-old Betty Anderson, whose father was a shoemaker and by all accounts a genius with leather, wore a large hole in her shoe. That shoe will go on display at the Alabama Department of Archives and History this year as it commemorates the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment and women’s right to vote.

Museum director John Hardin looked for items, such as clothes, shoes, and hats, worn by Alabama women seeking voting rights. Betty’s shoe, which she wore while marching for the vote for African American men and women, is an “awesome” addition to the collection, he said.

Remembering the Voting Rights Movement

This year also marks the 55th anniversary of the voting rights movement centered in Selma, where schoolchildren, teachers, parents, and pastors worked with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and others seeking the right to vote. In 1965, in Selma’s Dallas County, African Americans were 55 percent of the population, and less than 3 percent were registered to vote.

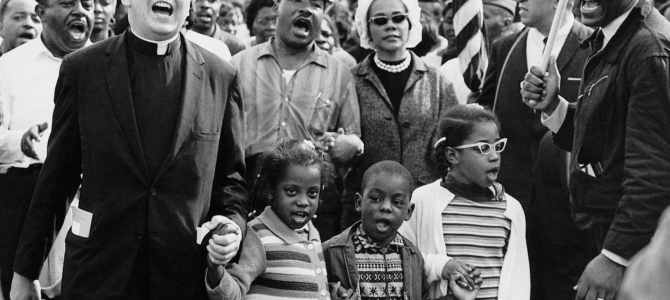

On March 21, 1965, King led a march from Selma to the state capitol in Montgomery to seek justice from Gov. George Wallace. The march culminated March 25 when more than 25,000 people from all walks of life, religion, and race, converged at the state capitol building, where King gave his famous “How long? Not long. … His truth marches on” speech.

Betty lived in Camden, 40 miles south of Selma, where 80 percent of the county population was black and none were registered to vote. She heard King speak at the local Baptist church on March 1 and worked alongside her parents, aunt, and local Lutheran pastors.

Her parents opened their home to out-of-state civil rights activists, fed the crowds, and sold chicken dinners to fund the work. Her father nearly lost his shoe repair business because of his involvement, but he was committed to the belief that all are created equal.

“King gave us courage. … He said, ‘Don’t be afraid.’ … We were afraid of the white people. We were afraid of being hurt. But King got us to the place where we wasn’t afraid. … We needed someone to stand for us who wasn’t afraid,” Anderson said, quoted in Bob Edelman’s “Down Home.”

Betty’s Fight for Her People

Betty joined her classmates that spring, marching from their school to the county courthouse just a block from her father’s shoe shop, fighting for their parents’ right to vote. Local deputies attacked them with tear gas and water hoses.

But Betty wasn’t deterred. She believed her people — brought as slaves to Wilcox County in 1846 — deserved the right to vote.

“I was raised in the church — my daddy was a deacon — and we always believed God loves us all equally. One of my favorite verses is ‘There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither slave nor free, there is no male and female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus.’”

So on Sunday, March 21, Betty and her older brother Bill, 17, arrived at the foot of the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma to join the marchers headed to the state capitol in Montgomery. Betty wore a pair of jeans, a shirt, jacket, hat, bobby socks, and her Keds, and carried a homemade knapsack with a change of underclothing, socks, sardines, and crackers. Her brother carried the peanut butter and blanket.

“We didn’t really know what we were doing, we just wanted to be part of it,” she said.

Betty and her brother were “really far back” in the crowd the first day, when thousands marched over the bridge along Highway 80, also known as Jefferson Davis Highway, surrounded by news media and the 1,000 Alabama National Guardsmen that President Lyndon B. Johnson had ordered protect them. They sang the songs of the movement, including Betty’s favorite, “Ain’t gonna let nobody turn me around.”

The first day, they walked seven miles to the first campsite. Like all the camping areas on the march, the land was owned by local African Americans. Tents were set up for male and female marchers, for guardsmen, and for the media, but Betty and her brother slept on their blanket pallet under the stars because their mother had told them to stick together. Each night was cold and damp — a typical March evening in Alabama — Betty remembers, and they didn’t get much sleep.

Betty’s Cracker Jack Sole

On Monday, the number of marchers decreased because the highway turned to just two lanes, through curving and hilly land and pastures with more cows than people.

The worst day was Tuesday. It rained all day. “We never thought about it raining,” Betty said. “We didn’t have anything to cover with. But we kept walking.”

Betty noticed her sock on her left foot was getting soaked. At the campsite that night, she took off her shoes and socks and saw a large hole in the sole of her shoe. She had no idea what to do. It was her only pair of shoes, and they were in the middle of rural Alabama with no money.

Suddenly, “a white lady came up out of nowhere. I don’t know who she was. She asked us what was wrong,” Betty recalled. “My brother said, ‘My sister done walked a hole in her shoe.’ The lady had a box of Cracker Jacks. I’d never seen them before. She dumped it on the ground, and shoved the box in the bottom of my shoe.”

“I walked that the rest of the way to Montgomery that way,” she said.

The Cracker Jacks box was specially designed in the 1890s to protect the molasses-flavored, caramel-coated popcorn and peanuts. It was a “waxed sealed package” that was moisture proof. That new box allowed the company to mass produce and sell Cracker Jacks worldwide. It also provided the protection Betty needed on the hard gravel and wet asphalt road she marched to Montgomery.

Inheriting Something Better than Shoes

The march ended Wednesday in Montgomery, where marchers stayed on the grounds of a local Catholic school. Betty and her brother had to leave from there because a friend offered their only ride back to Camden. But it wasn’t the end of her activism. That summer, Betty went to Jackson, Mississippi, to help register African American voters. In August, President Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act.

Today, Betty owns the Shoe Shop Museum, featuring her father’s work in both shoe leather and the movement. The jeans she and her brother had marched and slept in for four days were so filthy that their mother planned to throw them out. Instead, her father proudly made them into aprons to use in his shop.

His certificate to vote, dated Aug. 26, 1965, is proudly displayed in a frame. Many visitors, white and black, tell Betty stories of the miracles her father performed with damaged leather boots and shoes. But Betty never owned a pair of her father’s shoes.

She did, however, inherit his work ethic and passion for justice and truth. “My dad is my hero. He never let nobody turn him around. It took years and tears, but he made it.”