An agreeable trend in American museum exhibitions has been their willingness to tackle a daunting challenge: How do you put on a successful show about an artist who is not as well-known as he or she ought to be in this country, in part because many of his or her works can’t travel to the United States?

We’ve seen excellent examples of this in recent exhibitions reviewed in The Federalist, such as the Tintoretto show held earlier this year at the National Gallery of Art, and the Charles Rennie Mackintosh retrospective at the Walters Art Museum. Once again, the National Gallery has risen to the aforementioned challenge, with a terrific new show on Alonso Berruguete (c. 1488-1561), an important artist you’ve probably never heard of, in part because most of his work is located in Spain and is too large to travel, but mostly because no one’s ever attempted to put together a U.S. show about him until now.

During the press introduction to the exhibition, “Alonso Berruguete: First Sculptor of Renaissance Spain,” exhibition curator C. D. Dickerson III pointed out that Alonso Berruguete came onto a Spanish art scene that was in need of a new direction, and decided that this direction was going to come from absorbing the lessons he could learn from Italian art.

Until this point, Spanish artists had been influenced primarily by Northern European artists, such as the Flemish painter Rogier van der Weyden (c. 1399-1464), or painters from Burgundy. These artists retained many medieval aspects in their work which, to Berruguete at least, seemed a stylistic dead end. The ambitious young Spaniard wanted to look elsewhere for inspiration, and to do that, like many ambitious young Spaniards before and after him, he had to pack up and leave Spain.

To that end, sometime in the early 1500s, Berruguete arrived in Italy, where he was to remain for more than a decade. He eventually found himself attached to the studio of Michelangelo (1475-1564), first in Florence and then later in Rome, where he initially studied painting but later focused mainly on sculpture.

By the time he moved back to Spain about 1517, Berruguete was well-aligned with the latest artistic trend taking root in Italy, a style known today as Mannerism. It drew many influences from the aspects of heightened drama and exaggerated anatomy employed by the Hellenistic artists of Ancient Greece, as reinterpreted by artists such as Michelangelo, Pontormo (1494-1557), and Rosso Fiorentino (1495-1540).

What distinguishes Berruguete, however, upon his return to Spain, is the fact that he wasn’t interested in merely copying or emulating what his Italian peers were doing. Instead, he wanted to take the fruits of his Italian education and combine them with the tastes and traditions of his own country. The end result was art that, for the first time, was Renaissance in style but unmistakably Spanish in feeling.

Berruguete’s Subjects Weren’t Play-Acting

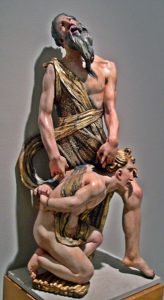

Take for example Berruguete’s “Sacrifice of Isaac” (1527-1532), one of the truly great works lent for the National Gallery’s exhibition. It illustrates the moment in the book of Genesis when Abraham is about to slaughter his son Isaac, just before an angel intervenes to stop the proceedings.

The powerful musculature and the contorted, elaborate poses demonstrate how the artist’s years of study under Michelangelo paid off. The figures also remind us of the Hellenistic sculpture group “Laocoön and His Sons” (c. 200 BC), a work which was famous in antiquity and had just been excavated while Berruguete was living in Rome. Berruguete knew it well and came back to reference it again and again throughout his career.

Yet what really sets the “Sacrifice of Isaac,” and indeed Berruguete’s sculpture in general, apart from the work of the Italian Mannerists during the same period is the piece’s visual richness combined with a heightened sense of pathos. Berruguete lavishly embellished many of the surfaces with gold leaf and painted intricate patterns on the sculpted drapery, in imitation of fabrics such as velvet brocade and silk damask.

Yet what really sets the “Sacrifice of Isaac,” and indeed Berruguete’s sculpture in general, apart from the work of the Italian Mannerists during the same period is the piece’s visual richness combined with a heightened sense of pathos. Berruguete lavishly embellished many of the surfaces with gold leaf and painted intricate patterns on the sculpted drapery, in imitation of fabrics such as velvet brocade and silk damask.

This stylistic choice reflected not only the growing wealth of the new and expanding Spanish Empire but also the past centuries of Islamic influence on Spanish art and design, as well as the sumptuously decorated robes depicted in many Hispano-Flemish paintings, or used to dress statues of Christ and the saints used in religious processions. The effect dazzles our eyes at first, but we’re then brought sharply back to reality by the highly emotional expressions of the figures, who display a kind of intense, personal spirituality that resonated deeply with a Spanish audience.

In this sculpture, Berruguete doesn’t depict Abraham as an old man humbly obeying God’s will. Oh, he’s obeying all right, but he’s shouting at heaven to make it absolutely clear that he’s extremely unhappy about it. Isaac, rather than being a passive victim, is screaming in unbelief at the injustice which he believes is about to take place.

These figures don’t passively or limply accept their fates. They wail and weep aloud in their suffering instead of trying to bottle it all up. There’s no idealized, pacific stoicism here because we are seeing the participants in real time, not in a kind of all-knowing, retrospective form of play-acting. This Abraham and Isaac don’t know what we know, which is how the heightened tension in this moment is ultimately going to resolve itself.

Berruguete Initiated a Cultural Tipping Point

A similar sense of emotional and physical tension characterizes another highlight of the exhibition, a massive “Calvary” group (c. 1526-1533) depicting the crucified Christ flanked by the Virgin Mary and St. John the Evangelist. With its combination of monumental scale, decorative surfaces, and heart-wrenching sorrow, the trio dominates a wall of the inner gallery of the exhibition and is placed at a height that forces observers to look up toward, rather than directly at, the scene.

A similar sense of emotional and physical tension characterizes another highlight of the exhibition, a massive “Calvary” group (c. 1526-1533) depicting the crucified Christ flanked by the Virgin Mary and St. John the Evangelist. With its combination of monumental scale, decorative surfaces, and heart-wrenching sorrow, the trio dominates a wall of the inner gallery of the exhibition and is placed at a height that forces observers to look up toward, rather than directly at, the scene.

Here we can see how determined Berruguete was to see Spain catch up artistically with Italy at depicting the human form. The carving of Jesus clearly demonstrates the artist’s understanding of human anatomy, which was highly unusual for a Spanish artist during this period. If Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo found it difficult to engage in anatomical studies in Italy without running into trouble with the local authorities, you can well imagine that such activities were nearly impossible in Spain, when the influence of the Inquisition was at its height.

In seeing large sculpture groups the size of the “Calvary,” or the exhibition’s partial mockups of some of Berruguete’s colossal altarpieces, one gets a good sense of how visually overwhelming his work must have been to his clients and countrymen when it was new. There was simply nothing else like this in Spain at the time, and as a result, it could be argued that Berruguete’s art marks the cultural tipping point at which medieval Spanish art began to recede into the past. It’s no wonder that, in addition to being appointed royal sculptor, he ended up receiving more requests for such large-scale commissions than he and his workshop could possibly take on.

If Berruguete’s exuberant figures become too much to take in after awhile, not to worry. Although the National Gallery show focuses primarily on his work in three dimensions, Berruguete was also an excellent painter and draftsman. Examples of his two-dimensional work, as well as works by some of his predecessors and contemporaries, have been chosen to add depth to the exhibition.

If Berruguete’s exuberant figures become too much to take in after awhile, not to worry. Although the National Gallery show focuses primarily on his work in three dimensions, Berruguete was also an excellent painter and draftsman. Examples of his two-dimensional work, as well as works by some of his predecessors and contemporaries, have been chosen to add depth to the exhibition.

Berruguete’s youthful “Salome” (c. 1512-1516), for example, on loan from the Uffizi Gallery in Florence, is a haunting piece from his years in Italy, showing how very much the artist was both aware and a part of the artistic innovations his friends and contemporaries were pursuing. One could easily mistake this as a Pontormo piece.

Surpassing Prior Artistry

The exhibit features Berruguete’s studies of life models and preparatory sketches, using everything from red and black chalk to sepia ink, including a drawing of one of Michelangelo’s Sibyls from the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. There’s even an incredibly rare engraving depicting “The Entombment of Christ” (c. 1540-1560) on loan from the British Museum, which is believed to be the only print the master ever created. It demonstrates how Berruguete was still managing to keep up with European artistic trends, as the circulation of artistic prints became more and more popular among collectors, considering how busy he and his atelier were with projects that often took many years to complete.

Yet even when he did work on small-scale pieces, such as the British Museum engraving, or on the delicately rendered “Lamentation over the Dead Christ” (c.1540-1550), an alabaster relief that was only recently rediscovered, we can learn a great deal about Berruguete’s outlook on his art and his times.

Yet even when he did work on small-scale pieces, such as the British Museum engraving, or on the delicately rendered “Lamentation over the Dead Christ” (c.1540-1550), an alabaster relief that was only recently rediscovered, we can learn a great deal about Berruguete’s outlook on his art and his times.

We can clearly perceive that in this instance, he was looking back to objects such as Ancient Greek and Roman tomb sculptures for inspiration. He didn’t limit himself to directly aping a particular Classical style, any more than he chose to let the Gothic style of the vast Cathedral of Toledo, the most important church in Spain at the time, constrain him when he presented it with a massive, carved choir stall executed in pure High Renaissance taste, all rounded arches and Corinthian capitals.

Berruguete may have wanted his audience to cast wider nets in searching for inspiration and knowledge, but he clearly believed that he, and the generations of Spanish artists who would come after him, were capable of matching and even surpassing what had been achieved both in the past, and elsewhere in contemporary Europe.

“Alonso Berruguete: First Sculptor of Renaissance Spain” is at the National Gallery of Art through Feb. 17. The show will then travel to the Meadows Museum at Southern Methodist University in Dallas, from March 29 to July 26.