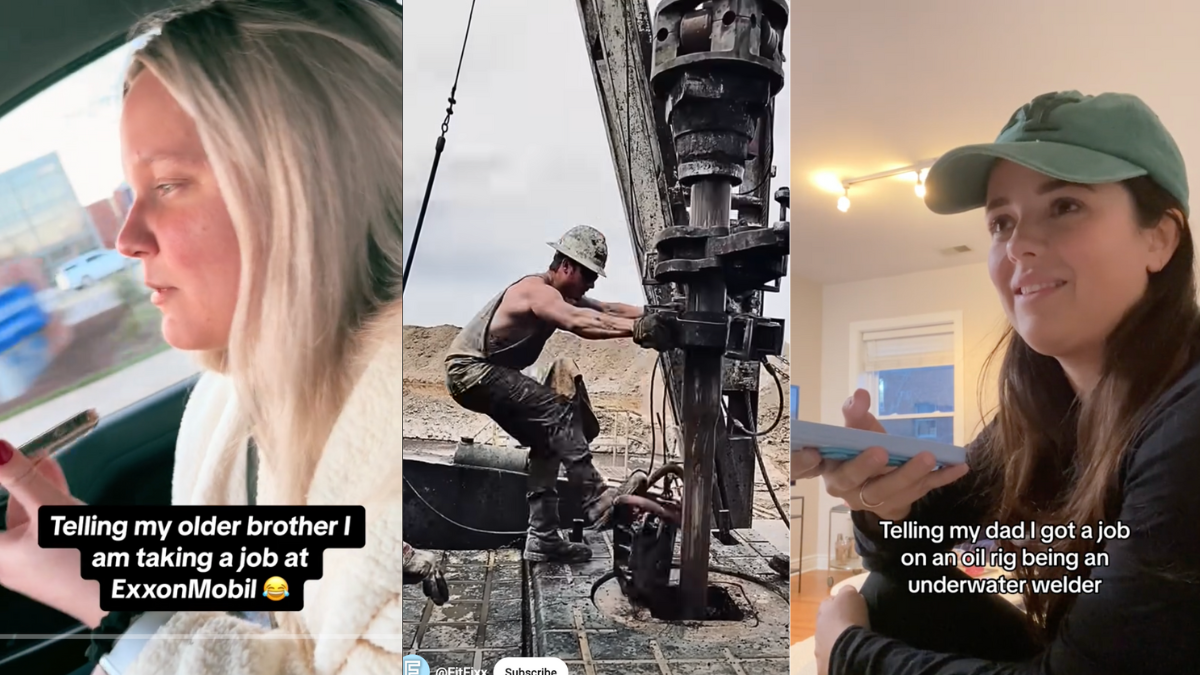

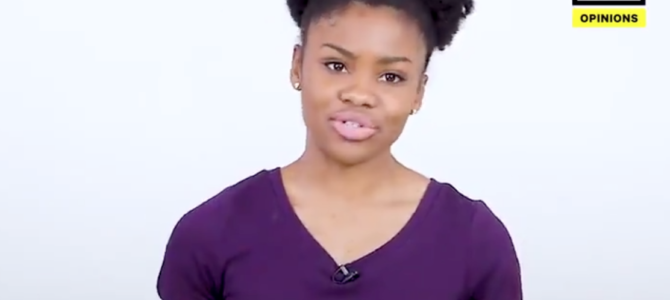

The latest episode of the feminist assault on language is the Now This video in which a bubbly young woman urged her audience to ditch the phrase “you guys” to move one step closer to smashing the patriarchy. She talked, enthusiastically, of “general reprogramming of people’s minds” and other wonderful and not at all dystopian goals. “Guys,” however, was the centerpiece of the program, because:

It, like many male default terms, should not be normalized as an all-encompassing phrase — innocent as it may seem. While we may understand the word means no real harm, with a deeper look, you’ll understand that we’ve been ignoring the cognitive impact on women as well as gender non-conforming folks, by only explicitly addressing the male-identifying individuals present.

She proceeded to talk for another five minutes, offering zero evidence that anyone is “cognitively impacted,” only a reason women should feel this way: because they are not mentioned specifically as women, and are therefore erased. But why is she telling me how to feel?

‘Hey guys’ seems innocuous, but here’s why you might want to try a different greeting pic.twitter.com/3Ep4Nmjf3d

— NowThis (@nowthisnews) September 9, 2019

No conclusive empirical proof indicates that feminist-inspired language tweaks are an effective tool for advancing women’s rights. When English speakers were compelled to start using “he or she” in place of the formerly gender-neutral, third-person singular “he,” we saw women entering the workforce en masse.

Unfortunately for the proponents of feminist language reform, that tells us nothing about causation. In fact, it’s more likely that the structure of our society and language usage both changed at once.

Does Changing Wording Change Thoughts?

From the very birth of the women’s movement in the 19th century, some feminists were irked by the marks male chauvinism left on language. Given their preoccupation with things such as women’s suffrage and working on the home front, it was not until the 1960s second wave that language reform became a hot topic among feminists and was quickly implemented in countries such as the United States and Sweden. In the United States in 1980, Casey Miller and Kate Swift published the influential book “The Handbook of Nonsexist Writing,” teaching English speakers how to break gender norms embedded in their language.

The biggest success story to come out of that exercise of ivory-tower feminism was ending the use of the word “man” and the pronoun “he” for a generic third-person neutral in mainstream writing. This reform, also known by the ghastly moniker “language planning,” substituted the first word with “person” or “one,” and the second with “he or she,” or, recently, “they.”

The effort was driven by the assumption that language determines cognition because people think in words and supposedly the pronoun “he” used for generic third-person encourages English speakers to imagine women as the second sex. We see the same zeal to reform language in, for instance, the push from the term “illegal immigrant” to “undocumented immigrant” to simply “immigrant,” or San Francisco banning the word “felon” in favor of “justice-involved individual.” Change the wording, and mentality will follow.

Feminist philosopher Camille Paglia frequently talks about the excess significance academics ascribe to language. These are the types who read and write for money and pleasure, and to whom language really is more detrimental than to most Americans. Yet what the George Lakoffs of the world see as “nuance” is to their compatriots the same concept dressed in different verbiage. Ordinary people feel frightened, suspicious, and resentful of language police.

Feminists Push Language As Far As They Can

So does switching from “man” to “person” make for a less sexist society? I seriously doubt it. Consider the case of Russian and Ukrainian. The two East Slavic languages share much history and structure. In Russian, the word most commonly used for man, or person, is человек (chelovek), and it’s of male gender. In Ukrainian, the word чоловік (cholovik), also of male gender, means husband. The word for human is людина (lyudina), and it is of female gender, with the corresponding pronoun “she.”

If feminizing or gender-neutralizing a language is an effective strategy for altering thinking about who gets to be the first sex, Ukraine provides a counterexample. Take Russia as a control group. The status of women has always been virtually indistinguishable in the two countries, with women facing the same issues, such as trafficking, workplace harassment, access to contraception, and family violence. The resemblance is not surprising, considering that the peoples of the two countries are very similar in mentality, even if they use opposite genders for the word “person.”

Then why bother changing language here? It would be creepier if that “reprogramming” strategy Now This is pushing actually worked, if people would begin thinking differently once expressions such as “you guys” are eliminated, but it’s creepy enough that it doesn’t.

There is no doubt in my mind that language carries traces of patriarchy — think how last names are passed on — yet I find it difficult to accept the premise that this history, lingering on the tips of our tongues, erases women. If a common word such as “guys” really is so perilous, how do American colleges, for instance, manage to graduate more women than men? Maybe “you guys” doesn’t mean “listen, men.” It probably means “you guys,” as in “everyone,” as people have used it for some time.

The real reason certain feminists push this agenda — and I’m not sure if they do it subconsciously or semi-consciously — is because they can. Those who can get an entire country with a population of hundreds of millions to twist into some sort of linguistic contraption every time they are searching for a substitute for the word “man” have power, and they are not too shy to use it. If the real goal of feminists is to reprogram thinking, filling hearts with fear about uttering any third-person pronoun is a good place to start.