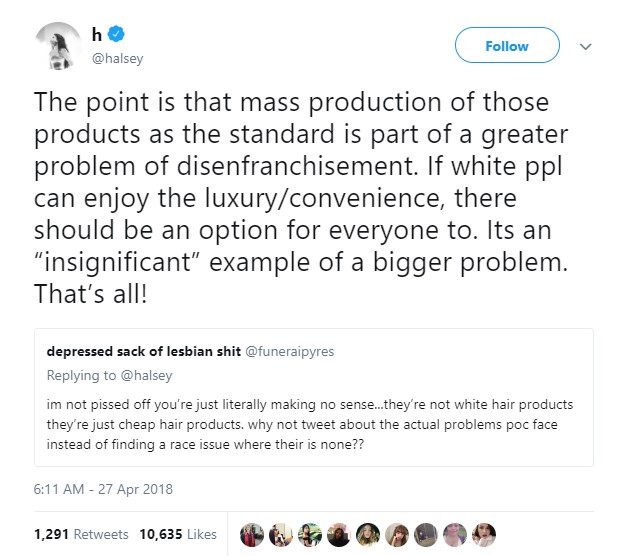

Singer Halsey is frustrated that hotels only provide “white people shampoo.” Here’s what she tweeted:

She goes on to claim that “mass production” of cheap hotel shampoo “is part of a greater problem of disenfranchisement” of people of color.

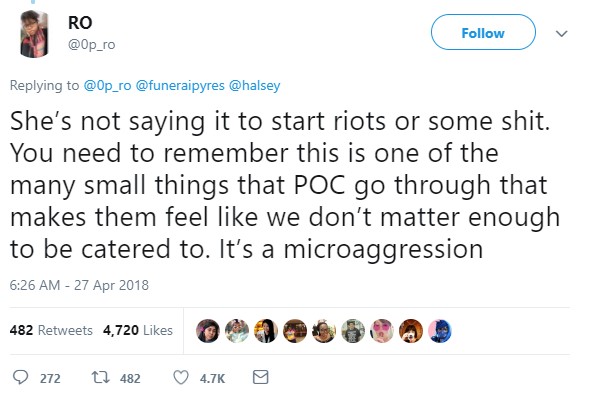

These comments sparked a Twitter discussion on “white privilege,” including at least one claim that cheap hotel shampoo constitutes a “microaggression.”

Many Twitter users were quick to point out that “white people” shampoo is just cheap shampoo. It is meant to be complementary, and even Halsey admits “50%” of hotel guests can’t use it, which means a lot of the people for which hotel shampoo is unsuitable are white.

Indeed, hotel shampoo is truly colorblind: it does not discriminate between black and white, but inflicts bad results on about half of its users regardless of race. Many white people have thick, curly hair or dry hair that won’t take well to the “watered-down” detergent. Hotel lotions are equally unsuitable for people with very dry skin, but I don’t claim that normal- to oily-skinned people are “privileged” or that dry-skinned people are “disenfranchised.”

Making Mountains Out of Molehills

As a white person with naturally straw-like hair, I can only get away with using hotel shampoo maybe once before my hair is completely stripped of moisture. To remedy this, I buy one-ounce squeeze tubes for a buck at Walmart and simply put my own products into them for travel. Problem solved.

I’m guessing Halsey knows this is the most obvious, easy solution, but she is using her frustration with this minor inconvenience to stir up dissension. It may be because she subscribes to social justice dogmas popular among celebrities today, or she wants to garner more publicity for her world tour.

For adherents to social justice ideology, nothing is too small an inconvenience to criticize and make into a race issue. These tactics are meant to force people into categories and increase tension among them. Such rhetoric divides people into the “privileged” versus “non-privileged or ‘oppressed,’” and further separates those who are “woke” and acknowledge white privilege (acceptable), and those who don’t (unacceptable).

But we would do well not to fall into the trap of arguing whether shampoo is “racist,” and instead point out how the free market works to serve the greatest number of people possible for the least expense.

This Is Just a Factor of Basic Economics

Firstly, hotel shampoos and conditioners are cheap and ineffective for so many people because they are “complimentary.” While their price is certainly factored into how much a hotel charges for rooms, it is hardly noticeable. Because guests consider it “free,” they don’t get too riled up about poor shampoo. Indeed, most people who find themselves on an unplanned trip and haven’t packed are grateful there’s any shampoo and conditioner at all.

Secondly, to the extent these products “work,” they are formulated to suit the greatest number of people possible. They would be targeted to the most common hair type: not too dry and not too thick. That hair type happens to belong to a whole bunch of white people.

That said, business models that attempt to cater to people of all hair and skin types can do very well, but they aren’t usually in the business of supplying low-cost complimentary soap. For example, Maybelline’s Fit Me line of foundations, found at virtually every drugstore in America, is so popular in large part because it has 40 shades. It was marketed from the get-go as something that will work for virtually any skin tone. Rihanna’s Fenty Beauty foundation line also has 40 shades, half of which are “deep.” This has helped the line become massively successful among people of color.

Overall, businesses filter themselves into the business models that will gain them the most customers for the most profit. Some will cater toward diversity, or toward minorities exclusively, and some will cater toward “the masses.” Some will meet in the middle, launching a product with a limited range, then expanding it to suit more people if the initial launch proves the product’s viability. That keeps R&D costs down, and therefore the final cost of the product.

It is not “disenfranchising” for stores in majority-white neighborhoods to carry a limited selection of products designed for people of color. What they’re trying to do is attract as many customers as possible. It makes sense for them to cater to the characteristics of the majority of their shoppers.

For example, in my local Walmart, many of the checkout aisles are stocked with Mexican cookies, complete with Spanish names and descriptions. This is because my neighborhood has a high population of Hispanics who tend to purchase these treats. (I also cannot find curry powder or garam masala in any of the big-box stores because the Indian population here is practically zero.) Similarly, stores in areas more densely populated with people of color are stocked with a much larger array of goods suited for their customer base.

It is not a “microaggression” for companies to cater to their bottom line. That bottom line is what allows you to have cheap emergency shampoo in your hotel room, and for you to eventually find a decent product that works for you at a price you can afford.

It’s Not Racism, It’s Called a Mass Market

I realize that advocates for white privilege theory and collective justice aren’t concerned with the fact that these companies aren’t motivated by racial prejudice in designing their products. They are concerned with the effect: that people of color often find themselves “the odd one out” due to their status as a minority. They will not be convinced that business decisions aren’t “discriminatory” (since discrimination has now been redefined as preference for one’s in-group), nor will they cease being divisive over trivial things like hotel shampoo.

It is nevertheless important to point out that the free market is the best way to get goods and services to the most people possible, with the highest value to price ratio possible. Observers who grasp this will be less likely to buy into social justice ideas, which are antithetical to free market principles, as they are focused on ensuring outcome equality rather than preserving the system that has made the U.S. economy the envy of the world, putting its poorest residents (disproportionately black) in the top 32 percent of the world’s wealthiest.

It’s true that blacks face myriad little things—insensitive comments, pale Band-Aids, sideways glances—that can add up over time to a feeling of being in the “out-group,” isolated, or undervalued. This is not easily remedied, because in any given diverse setting, someone, or a group of someones, will be a minority, and they will not be catered to like the majority is.

And each of us have our own setbacks that don’t have to do with the color of our skin, whether it’s relatively major things like physical disability, growing up poor (like my mother did), or lacking access to quality schooling, to relatively minor things like being stigmatized for having a big family, or having moderate acne or another skin condition that requires expensive products and can’t handle hotel soap—or, yes, having thick, curly hair.

There are so many ways to divide Americans into “in-groups” and “out-groups” that government intervention cannot remedy them all. I grew up homeschooled and Christian. This put me in an out-group in a variety of settings, especially college, but I don’t expect the world to cater to my minority status in faith and education as long as my basic constitutional freedoms are protected.

The best we can do in a diverse country like ours is to protect and participate in a free market, to be tolerant and kind and mindful of the disadvantaged, especially those who may be “less visible” from our vantage point, and to not allow minor inconveniences that have nothing to do with bigotry to agitate us, much less stir up strife in the public sphere. To be more than mildly and briefly irritated about things on the level of hotel shampoo is to be irritated all the time, for the rest of your life.

So don’t be Halsey, but maybe pack your own shampoo.