Reviewing Michael Wolff’s “Fire and Fury” presents a challenge for those of us tired of a media environment where the dominant voices consistently try to have it both ways. One of the differences between what happens when an author and a gossip columnist sit down to write a book is that the former tends to make every effort at disguising and protecting their sources, while the latter doesn’t particularly care.

In fact, it can be in the interest of a good gossip columnist to telegraph directly who’s said what nasty thing about someone else, in the interests of getting a vengeful nasty thing said right back to him by the offended party. Careful authors and journalists cultivate relationships with a wide variety of sources so as to avoid bad information or being led down an inaccurate path. Gossip columnists don’t particularly care if the path is inaccurate, so long as it gets attention and results in more fuel for the fire.

So while a solid author or journalist might see their writing as an attempt, as Henry Luce did, “to come as close as possible to the heart of the world,” the gossip columnist is more akin to Alice Roosevelt Longworth: “If you haven’t got anything nice to say about anybody, come sit next to me.”

Wolff’s book is the book of a gossip columnist — an entertaining one at that, but one who has a strong penchant for disregard for the facts and for thorough sourcing, particularly when these interfere with a narrative. It begins and ends with Steve Bannon, who Wolff makes no effort to disguise as his primary source for, well, virtually everything in this book.

Bannon is the main character in this story, with multiple chapters focused almost exclusively on what Bannon’s role is within the West Wing drama, even to the point of adopting his unique language and shorthand about his various rivals. The book overall reflects his viewpoint as the new world of the Washington DC political environment, which he spent his career railing against, now places him as a cog within the machine.

Wolff fawns over Bannon repeatedly in ways that ought to make even the most credulous reader blush. The opening sentence describes Bannon in January of 2017 as “among the world’s most powerful men”, and the closing passage describes a Bannon boldly proclaiming support from the most powerful Republican donors — the Mercers, Sheldon Adelson, Bernie Marcus, and Peter Thiel — as he begins to build a campaign organization for a 2020 run for the White House. This being Wolff, there is no indication that he checked with any of these donors about this Bannon claim being true (and donors are beginning to deny it). But truth is not the point of this book, after all.

That’s the real problem with this book. Brian Stelter and Jake Tapper got into a Twitter back and forth the other day, with Tapper taking issue with Stelter’s contention that the book “rings true” in certain respects.

Having many errors but “ringing true” is not a journalistic standard.

— Jake Tapper (@jaketapper) January 6, 2018

Do you believe Wolff’s assertion that 100% of the president’s senior advisers and family members questions his intelligence and fitness for office? That’s the main argument of the book.

— Jake Tapper (@jaketapper) January 6, 2018

It’s certainly possible to argue that parts of the book do indeed ring true, but they are overwhelmingly the portions where Wolff is already covering ground journalists have unearthed before him, and where he simply adds color to the tale. A typical Wolff move in this book is to add that Anthony Scaramucci was drinking heavily with Kimberly Guilfoyle the night he called Ryan Lizza for the interview that ultimately lit him on fire.

More problematic is where the book ventures far afield from the New York media gossip world Wolff knows so well. That’s what could lead Wolff to imply that Donald Trump, who had been complaining about John Boehner for years, actually didn’t know who he was in 2017. That’s what could lead Wolff to claim Kellyanne Conway led a “small-time down-ballot polling firm” with no national campaign experience, instead of actually being a longtime prominent pollster for Republican candidates (including presidential ones) and corporate clients.

Ok, I’m calling baloney on this. As a junior munchkin pollster, I remember being on major corporate projects @kellyannepolls led. She was a Gingrich 2012 pollster. “Small time” is insanely unfair and “never involved in a national campaign” is verifiably false. pic.twitter.com/fL0xhz1vRa

— Kristen Soltis Anderson (@KSoltisAnderson) January 5, 2018

That’s what could lead Wolff to describe Stephen Miller as an “effective intern” for the Trump campaign with no real policy knowledge, when in reality (whatever you think of his policy views) Miller was one of the most experienced policy players early on in Trump-world, and even aided in creating its signature immigration policy paper even before joining the campaign. But Bannon calls him “my typist,” and this must ring true.

I'm no Miller fan but the idea that he didn't know anything about immigration policy is absurd–he worked on it with Sessions for years. This is why you can't trust Wolff's assertions, which often demonstrate his own blithe ignorance. https://t.co/kn8vmcSxhq

— John Podhoretz (@jpodhoretz) January 4, 2018

It’s no accident that in each of these descriptions, Wolff chooses to flatter his primary source’s frame. His criticisms of Reince Priebus, Sean Spicer, Jared Kushner, Ivanka Trump, Donald Trump Jr., and even Anthony Scaramucci are Bannon’s criticisms. The book is full of plaudits for Bannon’s capacity for historical reference, his vision, and his stature. Its strongest critique is that he and his public relations associates in Breitbart world are disorganized, and that he has liver spots and jowls.

It describes Bannon as “the heavy of the organization,” whose “mix of insults, historical riffs, media insights, right-wing bon mots, and motivational truisms” fascinated the president and challenged his foes. Yet he is also depicted as a “soothing voice” and “a daydreamer” about the role of government, who attempted at various turns to balance against the president’s worst instincts. No wonder Bannon now regrets his role in the book while also not denying his statements. Perhaps he expected more subtlety.

Similar compliments are extended to others occasionally. Wolff positively gushes over brief White House Deputy Chief of Staff Katie Walsh, describing her as “clean, brisk, orderly, efficient,” a “righteous bureaucrat” and “a fine example of the many political professionals in whom competence and organizational skills transcend ideology.” High praise for someone who has never actually been a bureaucrat! You want a job recommendation, get you a Michael Wolff.

You can tell whom Wolff likes and dislikes throughout this book given the lack of restraint in his compliments and denigration. But you can also tell where Wolff’s lack of familiarity with an issue leads to inaccurate and occasionally outright terrible analysis of what was really going on in the Trump White House’s relationship with Congress and the rest of the GOP.

For example, Wolff’s careless depiction of Paul Ryan as a politician who “cared so little about the [health care] issue” will prompt a chuckle, given that Ryan made his bones on crafting prominent and controversial reforms of our nation’s largest government health care systems. Wolff displays no understanding whatsoever of the detailed reasons the health care vote failed last summer, and he doesn’t try to explain it. Bannon says “I hung back on health care because it’s not my thing,” so Wolff does the same, depicting it merely as an exercise in blame-shifting.

Wolff’s claim that the faultlines of the Republican Party are being restructured around their level of approval from Jared Kushner and Ivanka Trump is equally laughable. Consider this passage: “[UN Ambassador Nikki] Haley, who was much more of a traditional Republican, one with a pronounced moderate streak – a type increasingly known as a Jarvanka Republican.” Odd — the only references to “Jarvanka Republican” that exist are in this book. It is not a term I can find any reference to prior to its publication. (It appears to be a pidgin version of “Javanka,” no “r,” a term Bannon has bandied about and Wolff is apparently misquoting — repeatedly.)

The idea that Nikki Haley is understood only in relationship to “Jarvanka,” even as she is characterized according to Wolff by a member of the senior staff (I wonder who) as “as ambitious as Lucifer,” does more than inaccurately reflect her status. It does the reader the disrespect of confusing a nickname with a faction. As Haley herself responded yesterday on ABC’s This Week: “I don’t know if it was 200 interviews with Steve Bannon, or if it was 200 interviews with himself.”

As Haley indicated, you ought to be forgiven for wondering what percentage of those 200 Wolff interviews were actually just extensive Bannon monologues. As a reader, I felt rather gypped. “Fire and Fury” was indeed supposedly based on 200 interviews over 18 months, but the book’s closing chapter is the ascendancy of John Kelly, which happened in the last week of July. After Bannon was pushed out following Kelly’s rise, it appears Wolff lost what remaining access he had to the White House.

You miss out on basically everything internal after July, which makes one wonder why there are so many basic typos and errors that disrupt the book (couldn’t they have caught “Trump Towner,” the multiple uses of “pubic” instead of “public,” or the fact that Dick Armey is not in fact a former speaker of the house?). If the reporting for this book effectively ended five months ago, what’s the excuse for this?

'@MichaelWolffNYC claims @realDonaldTrump didn't know Boehner was Speaker. Yet he thinks @DickArmey was fmr Speaker pic.twitter.com/JPpRbuYbp3

— Chris DeRose (@chrisderose) January 5, 2018

Via WashPost's @MarkBerman: This page in Wolff's book has 3 errors. @HilaryRosen's name is misspelled. Wilbur Ross was the commerce nominee, not labor. And Berman says he's never been to this restaurant. pic.twitter.com/tRqxmU3Sct

— Brian Stelter (@brianstelter) January 5, 2018

Michael Wolff has written a book that makes its most significant claims based on little more than hearsay. He maintains that to a person, those around Trump view him as a child unfit for the office, dangerous and stupid. He maintains this is the view held by Steve Mnuchin, H.R. McMaster, Tom Barrack, Gary Cohn, Reince Priebus and more.

He writes that Rex Tillerson’s fate has been sealed and Kelly is unlikely to surpass Priebus’s tenure (for futures purposes, he’d need little more than one more month to do that). He maintains that Kushner and Ivanka Trump “made an earnest deal: If sometime in the future the opportunity arose, she’d be the one to run for president” — an utterly unsourced claim that runs against the facts that Ivanka had overwhelmingly shunned politics prior to her father’s run, and not-so-quietly expressed frustration with the idea.

We live in times that demand more skepticism. But “Fire and Fury” is not a book written for the incredulous. It is a book written for people who will believe just about anything if it is told to them in a juicy enough way, if it tickles their assumptions and fulfills their worst suspicions. It is intentionally crafted that way, as the author has indicated, to further “the perception and the understanding that will finally end … this presidency.”

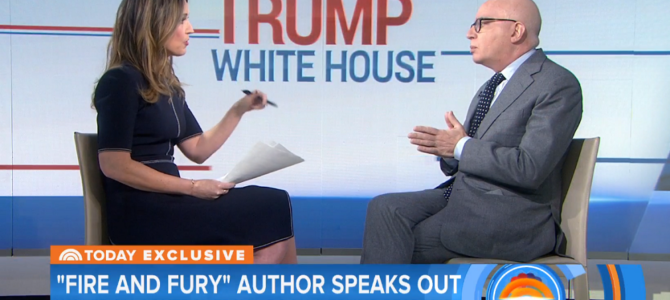

It’s important to understand what Wolff is doing here: he is not presenting this book as a breezy gossipy low-sourced score-settling dramafest, but as a tome of significant import to the future of the country. On Sunday morning’s “Meet the Press,” Wolff presented the book as “this is 25th Amendment kind of stuff.” Then when Todd asked about the many errors in the book, he said this:

TODD: ‘There are a lot of little errors … It adds up. Why shouldn’t a reader be concerned about some of these mistakes? … Do you regret some of these errors … It feels as if you didn’t get a copy edit.’

WOLFF: ‘I think I mixed up a Mike Berman and a Mark Berman, for that I apologize. But the book speaks for itself. Read the book. See if you don’t feel like you are with me on that couch in the White House. And see if you don’t feel alarmed, as you say.’

There is a problem with holding Wolff’s book up as the impetus for this alarm, though (it’s been going on for almost a year, actually). Given Bannon’s outsized role in framing the narrative within it, this book’s sales performance tells us a great deal about this moment. So much of the Left’s self-identity is tied up in its sense of abiding superiority, both moral and intellectual, that has given rise to progressivism’s coterie of Tracy Flicks — high school overachievers who resent the country’s lack of deference, and view the Right as shot through with immaturity and ignorance.

Yet how much do you have to squash your own intellectual skepticism to attach so much importance to a book largely repeating wholesale the tales of someone many on the Left were previously convinced was a white nationalist/supremacist? How much willingness must you have to normalize the same “fake but accurate” approach you have deigned to criticize?

At the point in “Fire and Fury” where Wolff engages in an explainer about David Halberstam’s “The Best and the Brightest,” you start to understand how low the expectation has become for political blockbusters. “Allegations from Bannon-sourced book by gossip columnist confirm their political point of view that president should be removed for being nuts, say cultural elite.”

In this Wolff is quite similar to his subject matter, which you might have been led to believe is the president of the United States. It is not. This book would be more accurately titled “Steve Bannon’s What Happened.” Either Bannon deserves strange new respect, or Wolff’s book is trash. Choose one.