In “That Hideous Strength,” C.S. Lewis imagined a cadre of coercive technocrats obsessively bent on fixing humanity through one ill-conceived, progressive program at a time. In his 1945 review of the book’s horrifying do-gooders, George Orwell stated, “Plenty of people in our age do entertain the monstrous dreams of power that Mr. Lewis attributes to his characters, and we are within sight of the time when such dreams will be realisable.”

Standing on the cusp of 2018, we are experiencing the dystopian future Orwell’s and Lewis’ books warned of. I submit as evidence the cultural Marxist hegemony’s imperious influence across the Internet. This power was on full display recently when Lewis Hamilton, the four-time world championship Formula One racecar driver, released a Christmas day video with his nephew where he blithely proclaimed: “Boys don’t wear princess dresses!”

He was obviously playing with his nephew. He meant the comment in jest. We aren’t privy to any information about what went on before or after the video took place. His nephew may have given a full-throated, candid retort, or his mother a well-deserved shellacking for posting family business on Instagram. We simply don’t know, and it doesn’t matter. Some were offended by the remark, and Lewis became an enormous problem for certain factions of the Internet.

Cue Ritual Abasement Before Mob of Pitchforks

My defense of Hamilton stops short of saying he exercised sound judgment by posting the video. Clearly he’s savvy and smart. A man doesn’t rise to his level of achievement in the absence of physical and mental rigor. He ought to have known better.

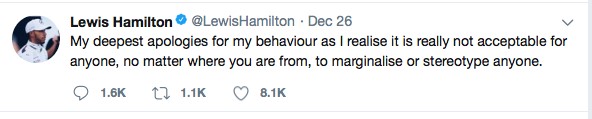

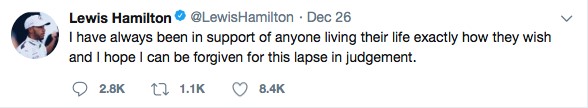

It’s a moot point, though. In that 13-second slip of time, Hamilton let loose his inner beliefs, and that was all that was necessary to prompt an attack. Although not everyone is hostile to his opinions and some even thought the video amusing, the fury of outrage achieved its desired result. Hamilton quickly issued a series of contrite apologies.

Just days later, however, Hamilton confused his detractors when he was caught surreptitiously “liking” tweets from people who supported his video comment. In all fairness, it can hardly be shocking to anyone that Hamilton “liked” tweets that were sympathetic towards him. Who doesn’t like people who are nice to them?

It was never confirmed whether Hamilton was agreeing with the tweets, or just “liking” them because it’s nice to be supported. But this small, almost imperceptible action (it was a like, not even a comment) was a bridge too far for his critics. Twitter lit up, accusing Hamilton’s apologies of being “insincere,” “hollow,” and the like.

Hamilton decided against trying to apologize again, and opted instead to perform a vanishing act. He cleared his Instagram account, and deleted tweets from his Twitter account. There’s no word on why. I hope he doesn’t disappear completely. The Internet needs Lewis Hamilton, because the Internet needs diverse, free thinkers.

What We Really Think Will Come Out Sometime

Hamilton’s Twitter rebellion, though fleeting, was refreshing. It was encouraging to see him behaving as his own man in support of his fans. The Internet will always benefit from public figures willing to exercise free, independent thought that doesn’t comport with the all-too-familiar narrative.

In John Bagnell Bury’s book, “A History of Freedom of Thought,” he makes the case, “If a man’s thinking leads him to call in question ideas and customs which regulate the behaviour of those about him, to reject beliefs which they hold, to see better ways of life than those they follow, it is almost impossible for him, if he is convinced of the truth of his own reasoning, not to betray by silence, chance words, or general attitude that he is different from them and does not share their opinions.”

To borrow from Bury’s argument, it wasn’t that Hamilton didn’t follow the rules; he provided several satisfactorily contrite apologies. Hamilton’s folly was that his beliefs betrayed him, and he called into question his accusers’ ideas and customs by suggesting “Boys don’t wear princess dresses” then “liking” tweets that supported his opinion.

‘Why Is It So Important to Destroy Each Individual?’

To understand why Hamilton’s minor act of solidarity was such an egregious offense, we have to understand the system he inadvertently chose to challenge. To do that, we must look to an original source of control through coercion. In Natan Sharansky’s autobiography of his time spent in the Russian gulag, “Fear No Evil,” he lays out why the KGB were so mercilessly intent on destroying and turning even the least threatening of prisoners.

“Why is it so important for the KGB to destroy each individual? Why is it that even if he has spent years in prison and represents no danger to it, the KGB still wants him to confess? There are several reasons. Every prisoner who recants is a potential influence other zeks to do likewise. And each one who breaks undermines support in the West for human rights. But beyond these self-evident reasons, there is something larger art work here, some kind of psychological imperative, as thought the KGB is so lacking in confidence that it has to prove itself again, and again, as though even a single holdout undermines everything it stands for and makes a mockery of its intentions.”

While not a perfect analog, I think Sharansky’s understanding of the psychology underlying the KGB’s motivation is sufficient to explain why Hamilton was castigated for “liking” tweets expressing unacceptable views. A single act undermines and mocks the entire effort.

For now, Hamilton has settled on self-censoring to end the attacks. But like Mary Katharine Ham and Guy Benson point out in their book, “End of Discussion,” “This move toward acquiescence isn’t just limiting. It’s dangerous for society.” Freedom of thought and expression is the measure of a healthy, robust society. We are blessed to live in a nation governed by a Constitution that recognizes these freedoms. But these rights necessarily presuppose there will be discord.

We will not all agree. Nor should we. Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes once wrote, “if there is any principle of the Constitution that more imperatively calls for attachment than any other it is the principle of free thought, not free thought for those who agree with us but freedom for the thought that we hate.”

This is in no way a capricious statement insensitive to the comprehensive effects of hateful thought or speech. I believe Holmes was fully aware of the implications of his words, and understood what hung in the balance. But it must be so. Otherwise the logical conclusion is a slippery slope into a systematic shutdown of our First Amendment rights and a return to tyranny. That is, after all, what our Constitution specifically safeguards against.

Applying Free Speech to the Internet Is Our Job

The Internet, on the other hand, is an inherently neutral system dispossessed of virtue. It is by nature the characteristic embodiment of its users. We have the power to make it a good or bad place in which to coexist. Moreover, the principles Holmes was speaking of may mean nothing to people beyond our cultural boundary lines. In the twenty-first century, an American concept of freedom now has to compete in the virtual marketplace. We can no longer take for granted that our protected speech is protected online.

It’s essential we continue to espouse the virtues of enlightened, free thought in aid of shaping how our virtual experience will look for present and future users. Only a free society has the moral and intellectual fortitude to tolerate competing points of view, to include the ones with which we don’t agree.

The Internet is big enough for everyone to share, but to remain so it must be a philosophical marketplace free from cultural Marxist limitations, open to the free exchange of ideas. We have an opportunity and duty as the beneficiaries of our own priceless liberty to help keep it so.

I’ll leave you with the insightful words of President Ronald Reagan as a reminder that we can never be passive about preserving our freedom. “Freedom is never more than one generation away from extinction. We didn’t pass it to our children in the bloodstream. It must be fought for, protected, and handed on for them to do the same, or one day we will spend our sunset years telling our children and our children’s children what it was once like in the United States where men were free.”