What does it take to get the public to reassess the life and legacy of a president?

It’s a question worth pondering in an age where media narratives and groupthink define perceptions and strain to write history in real time. However, when it comes to polarizing public figures, often we find that what think we know about someone is at odds with the facts.

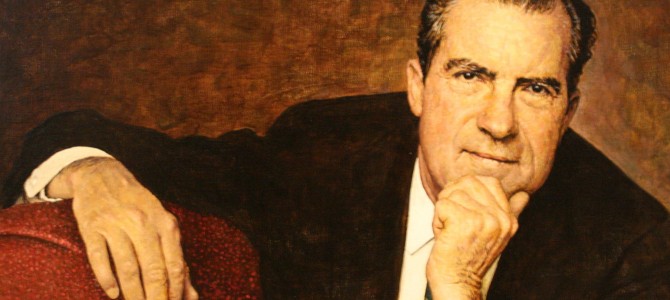

Case in point: Of all the political leaders of his generation, the historical consensus about Richard Nixon remains the most divided and contentious. But despite the attention historians and journalists have focused on Nixon —most of it negative—there has been less true historical scholarship than one would expect, and more casual repetition of anecdotes, clichés, and conventional wisdom.

In The President and the Apprentice: Eisenhower and Nixon, 1952-1961, historian Irwin F. Gellman seeks to fill that void, and does so in a readable and extensively researched volume. Focusing on the eight years Nixon spent as Dwight D. Eisenhower’s vice president, Gellman explores the relationship between the two men while rebutting much of the erroneous folk wisdom that has been repeated through the years about Nixon’s role in the administration.

This explicitly revisionist history, which follows Gellman’s 1999 volume, The Contender: Richard Nixon: The Congress Years, 1946-1952, is the result of the author’s twenty years of study in the National Archives, the Nixon library, the Eisenhower library, and other repositories of historical documents. The contrast with earlier historians’ efforts, many of them written without use of these primary sources, is startling. The President and the Apprentice should shift the historical assessment of Nixon’s vice presidency considerably.

Collateral Damage

After Eisenhower’s victory over Senator Robert Taft at the 1952 Republican National Convention, Nixon’s name was at the top of his list to join him on the ticket, and the party’s power-brokers agreed. The campaign that followed resonates with our own times. The incumbent president, Democrat Harry S. Truman, and his party’s nominee to succeed him, Illinois Gov. Adlai Stevenson, dismissed the threat of communism, even after losing China to red revolution; similarly, our own president and his would-be Democratic successors downplay the danger of radical jihadists, despite having lost much of Syria and Iraq to an apocalyptic caliphate. (In other places, the analogy is woefully inapposite: The Republicans of 1952 had Eisenhower, the general who led the free world to victory over fascism. We have Donald Trump.)

The pivotal event in the 1952 campaign was controversy over a fund Nixon’s backers set up to help defray his expenses while in the Senate. Such funds were common and legal, and Nixon’s was not kept secret (as Stevenson’s much larger fund was), but talk of a “slush fund” detracted from the Republicans’ message of cleaning up corruption in government. Nixon addressed the nation to explain his financial affairs in what came to be known as his famous “Checkers Speech.”

Eisenhower did not immediately spring to Nixon’s defense, but waited to see how the situation would develop. To Nixon, this signaled hesitancy from Eisenhower about Nixon’s fitness for office, and that theme is the one popular historians have most often repeated ever since. In truth, as Gellman demonstrates, Ike’s behavior was more indicative of the difference in style between the two men.

Nixon’s career was that of a partisan politician, and he expected that a Republican would defend another vigorously against every Democratic attack. Eisenhower approached politics as a nonpartisan and with the outlook of a general; some collateral damage was acceptable where it did not endanger the overall effort. He observed Nixon’s efforts, assessed the overwhelmingly positive popular response to the speech, and moved on with the campaign, publicly praising his running mate’s courage in a tense situation.

The Mentor and the Protégé

As the book’s title suggests, the president and vice president who entered office in 1953 after their landslide victory were not equal partners. Eisenhower, the victorious commander of the Second World War, had no equal. While he consulted his cabinet and advisers as necessary, no one in the administration doubted that Ike set the policy. But neither was his vice president a useless appendage.

Eisenhower had been deeply disturbed in 1945 when, after Franklin Roosevelt’s death, Vice President Truman ascended to the presidency with little knowledge of his predecessor’s most important policies and aims. He was also mindful that his age, sixty-two, placed him among the oldest presidents ever to take office. (Not, however, the oldest, as Gellman erroneously states. William Henry Harrison, Zachary Taylor, and James Buchanan were all older than Eisenhower at their inaugurations.) With this in mind, Eisenhower resolved to involve Nixon in all of the administration’s major initiatives.

The result was a mentor-protégé relationship, especially in the foreign affairs arena. Eisenhower involved Nixon in cabinet and National Security Council discussions, even tasking the vice president with chairing cabinet meetings in his absence, which was unprecedented in American history. In 1954, Nixon addressed the nation on television to explain the administration’s “New Look” policy, which balanced military preparedness and a growing nuclear deterrent force with fiscal solvency and a return to a peacetime economy after the disruptions of the Korean War.

Eisenhower also dispatched Nixon around the globe, not just on the funeral and coronation circuit expected of vice presidents, but on true fact-finding and diplomatic consultation missions to Asia, Africa, Europe, and most famously Latin America, where Nixon encountered hostile crowds in Peru and Venezuela. It is difficult to imagine any recent president giving such a breadth of weighty responsibilities to his second-in-command.

In domestic politics, Nixon had greater experience than his boss. Here, too, Eisenhower held the policy reins firmly, but he gave his vice president considerable responsibility. Eisenhower and Wisconsin Sen. Joseph McCarthy agreed on the danger of communism and the need to guard against Soviet espionage, but the president had a visceral dislike of McCarthy’s recklessness and, in particular, his attacks on Eisenhower’s beloved army. Nixon, who had served in the Senate with McCarthy, worked as a liaison with the Wisconsin senator’s wing of the party and sometimes managed to smooth over differences.

Even after McCarthy’s decline, Nixon worked as a go-between with other congressional leaders, including on the important issue of civil rights. In their 1956 reelection campaign, Nixon played a more active role than Eisenhower on the speaking circuit, owing partly to his greater entrenchment in partisan politics, and partly to Eisenhower’s reluctance to risk his weakening health by undertaking an arduous speaking schedule.

Nixon’s Leadership

Eisenhower’s health is a major theme of the book. A heart attack in 1955 left Ike hospitalized for six weeks. An attack of ileitis in 1956 and a mild stroke in 1957 also saw the president at less than full capacity for extended periods of time. During these times, he relied heavily on his cabinet, his staff, and especially his vice president.

Beyond chairing cabinet meetings and representing the administration in the public eye, Nixon’s leadership during Eisenhower’s ill health papered over a constitutional leadership gap that was not securely fixed until the passage of the Twenty-fifth Amendment to the Constitution in 1967. In that respect, Eisenhower’s planning paid off. Had he died in office, the nation would have been spared the problem of a new president having to learn on the job.

The Eisenhower administration was popular, but its popularity did not extend beyond the occupant of the White House. Eisenhower and Nixon entered office with slim Republican majorities in both houses of Congress, but both were lost in the 1954 midterm elections. Republicans would not retake the Senate until 1981, and the House would retain its Democratic majority until 1995. Eisenhower’s leadership of the nation did not carry over into leadership of the party, to Nixon’s frustration. Nixon wanted Eisenhower to expend some of his personal mandate in building up the rest of the Republican Party. His failure to do so was a rare source of tension between the two men.

Finding Clarity

A lifelong non-partisan, Ike was determined to stay above the partisan fray as much as possible. The Democrats, reluctant to attack a personally popular war hero and national grandfather figure, obliged him. Instead, they concentrated their political and personal enmity on the second half of the ticket. This redounded to their benefit when the Democrats made massive electoral gains in the 1958 midterms and, even more so, when Nixon proved unable to win election to the presidency in his own right in 1960 despite Eisenhower’s continued popularity.

One source of Eisenhower’s popularity was his remove from the nitty-gritty of party politics. No candidate could inherit that mantle in 1960, least of all Richard Nixon, the partisan warrior the Democrats has spent the last eight years vilifying. That vilification continued after his death and into our own time, and while Nixon justly earned a lot of enmity as a result of Watergate, it’s also true that many of the partisan attacks leveled at him before and since have been in spite of the available evidence.

The President and the Apprentice is a welcome addition to the scholarship, and should drive the historiography of Richard Nixon away from lazy invective and back toward true historical analysis. In that respect, the book does exactly what good histories should all strive to do—make us resolve to assess the figures of our current age with more clarity and less caricature.