Yogi Berra, who died last night at age 90, was one of the last of his generation of baseball stars, but he was also truly one of a kind in many ways. The closer you look at his life and his record, the more impressive he looks. He really may have been the best catcher in the history of baseball, and if he was, the reason why has less to do with conventional athletic talent than his durability, consistency, personality, hard work, and how uniquely suited he was to the catching position and the team game of baseball.

Yogi was the starting catcher for seven World Championship teams and nine pennant winners, plus being a part-time catcher or starting outfielder for three other World Championship teams and four pennant winners, plus managing two pennant winners with two different franchises out of his five full seasons as a manager, plus seven trips to the postseason (three of them for World Championship teams) as a coach with three different franchises. Twenty-one of the 35 World Series played between 1947 and 1981 featured Yogi Berra as a player, manager, or coach. Oh yeah, before that, he was at D-Day.

Yogi at Normandy

Before Yogi ever set foot on a Major League diamond—when he was just a teenager with one year of Class B baseball behind him—he joined the Navy and participated in the “Great Crusade” to liberate Europe, serving on a “rocket boat” off Normandy supporting the D-Day landings, which he described as a grand adventure:

I was on a rocket boat…with 12 rockets on each side, five machine guns, a twin-50 and the 330s. And only 36 feet, made out of wood and a little metal…It’s amazing what that little boat could do, though…We could shoot out rockets. We could shoot one at a time, two at a time, or we could shoot all 24 at a time. We went in on the invasion. We were the first ones in, before the Army come in. …[W]e stand out about 300 yards off the beach, and we see what happens. If we ran into anything, we fire. Fortunately enough, nothing happened to us. We were lucky. But, you just get so tired, you got to say that. But then, I enjoyed it. I wasn’t scared. Going into, it looked like Fourth of July. It really did. Eighteen-year-old kid, going in an invasion where we had – I’ve never seen so many planes in my life, we had going over there.

Yogi was hardly the only player of his generation to see combat. Warren Spahn fought at the Battle of the Bulge, Ralph Houk was a highly-decorated Army Ranger who performed staggering feats of courage, and even among guys who were big, famous stars before the war, Bob Feller saw naval combat in the Pacific as a gunner on the USS Alabama. The list goes on and on. It was the norm for the men of that day, inside and outside the game.

The baseball world that Yogi’s Yankees dominated between 1947 and 1964 saw great changes: racial integration, the first franchise moves in half a century, the first lasting expansion since the 1880s, air travel, routine televised games, the beginnings of modern bullpens, the rediscovery of base stealing. But the men who played it were also different from the players before or after because so many of them were hardened by war and matured beyond their years.

Ironically, Yogi’s wartime service helped his career. While teammates and opponents were taking two-year stretches away from the game due to the draft, and while contemporaries a little older got a late start to their careers, Yogi was done with the military by age 21. Between 1947 and 1950, Yogi would gradually take over as the Yankees’ everyday catcher, and would—as discussed below—give new meaning to the concept of an everyday catcher. In January 1949, he married his wife, Carmen, who died last March after 65 years of marriage.

Yogi’s death severs one of the last links to that generation, which in turn was the last links to some of baseball’s earliest days. Connie Mack was still managing the A’s when Yogi became the Yankees’ regular catcher. Yogi once caught Cy Young, for the ceremonial first pitch opening the 1953 World Series (Cy was 86 then, the same age Yogi passed in 2011).

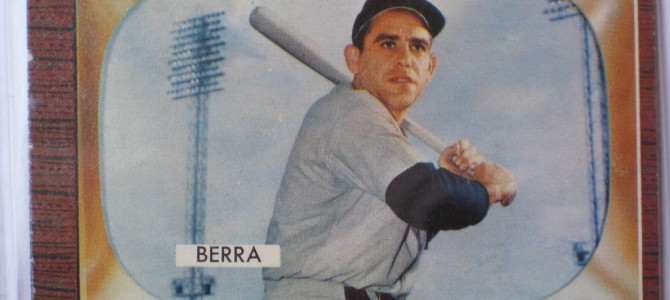

Berra, Batting Cleanup

Yogi was a tremendous hitter, but he was not the very best-hitting catcher of all time. By any statistical measure, that honor goes either to Mike Piazza (among Major League catchers) or Josh Gibson (who was kept out of the Major Leagues by the color line; sadly, while Gibson was only 14 years older than Yogi, he has been dead for 68 years). Still, when I ranked the best catchers in baseball history in 2009 by looking solely at the years of their primes, I concluded that, adjusting for the context of his time, Yogi would rank either third or seventh depending if you focused on his seven-year or 12-year prime, and by slugging percentage would trail only Piazza and Bench.

You can read the whole article for an explanation of the charts and methodology, but an important point is that I didn’t rank the catchers just by their offensive productivity, but also on their playing time, adjusted per 162 scheduled games (accounting for the slightly shorter 154-game schedule of Yogi’s era and even shorter schedule in early baseball). More advanced stats have their own assessments of Yogi’s purely statistically measurable contributions—for his whole career, the Wins Above Replacement metric places Yogi sixth among players who spent at least half their games behind the plate, just a hair behind Piazza:

I suspect this understates Yogi’s contributions, as no position is harder to entirely capture statistically than catcher, and despite a constantly revolving cast of pitchers and infielders, no catcher’s teams ever won with the regularity of Yogi’s.

It’s worth noting that, while his athletic gifts were not as obvious as those of a Mickey Mantle, they were ideally suited to his role. Yogi was not a notably patient hitter, but he had the Vladimir Guerrero-like gift of such amazing hand-eye coordination that he could hit basically any ball thrown anywhere: the modern practice of catchers standing far off the plate during intentional walks arose after Yogi proved he could dive far enough to hit balls put purposely out of the strike zone in efforts to walk him.

As a result, he was famously impossible to strike out, never whiffing more than 38 times in a season and notching at least as many home runs as strikeouts in six different seasons (in 1950, Yogi hit 28 home runs and struck out 12 times—one of only four players to hit twice as many homers as strikeouts in a full season since 1893).

Despite a lack of natural foot speed, but perhaps partly due to being a left-handed pull hitter, Yogi hit into very few double plays for a guy who batted with a ton of men on base (he usually hit fourth or fifth), hit the ball hard and rarely struck out. He hit into double-figure numbers of double plays just five times, with a career high of 16. Among 124 players since 1946 to bat at least 3,000 times and catch at least half their career games, Yogi’s rate of 10.5 GIDP per 600 plate appearances is the thirteenth lowest, and only two of the guys ahead of him—Darrell Porter and Tim McCarver—had even 70 to 75 percent as many career plate appearances as Yogi.

Casey loved to hit-and-run (his teams perennially turned vastly more double plays than they hit into), and Yogi’s amazing bat control made it possible to send the runners, knowing he’d always put the ball in play no matter where it was thrown. Yogi struck out just under 30 times per 600 plate appearances for his career, but that dropped to 27.2 with a man on first base and less than two out, 23.3 with a man on first base and nobody out, 21.8 with the bases loaded and nobody out, 20 with men on first and third and nobody out, and 13.6 with men on first and second and nobody out.

While Yogi’s other offensive numbers were not helped by Yankee Stadium—it was a severe pitchers’ park in the 1950s, and he hit .286 career at home, .283 on the road—he definitely capitalized on the short right-field porch: for his career, he hit 210 home runs and just 118 doubles at home, but 148 homers and 203 doubles on the road, as balls he pulled down the line in places like Washington’s Griffith Stadium and Philadelphia’s Shibe Park landed short of the seats.

The best pitchers in the league had no great success against Yogi. Against the Yankees’ chief rivals, the Indians, Yogi’s career line was .295/.354/.474 against Hall of Famer Early Wynn, .281/.375/.461 against Hall of Famer Bob Lemon (with 23 walks and three strikeouts), .286/.330/.495 (with three strikeouts in 97 plate appearances) against Hall of Famer Bob Feller, 324/.377/.514 against Mike Garcia, .369/.461/.754 against Art Houtteman. What about the Tigers? .365/.441/.865 against Hall of Famer Jim Bunning, .333/.358/451 (with no strikeouts in 53 plate appearances) against Hall of Famer Hal Newhouser, .349/.429/.651 against Dizzy Trout, .311/427/.473 against Virgil Trucks, even .270/.303/.431 against Frank “the Yankee Killer” Lary. He hit .284/.335/.483 against Billy Pierce. About the only star pitchers of the age to consistently handcuff him were Mel Parnell, Camilo Pascual, and Herb Score.

The Iron Man in the Mask

More impressively and uniquely, nobody ever had catching take as little out of him as it took out of Yogi Berra. Physically, the stocky, powerfully-built Yogi was basically designed to be a catcher (Bill James described him as looking like, if he was a piece of furniture, you’d sand him off some). While he was a heckuva hitter and defensive catcher as well as handler of pitchers, his real calling card in the argument for the greatest catcher of all time—and integrally related to why his teams won so much—was his unique combination of durability and consistency (as the military saying goes, quantity has a quality all its own).

We may not be able to compare the durability records of twenty-first-century pitchers to their predecessors without significant adjustments, because today’s pitchers throw harder more consistently and throw a wider quantity and variety of strain-producing breaking balls. But the job of a catcher has, if anything, gotten a little easier since Yogi’s day with improvements in the equipment. Yet no catcher, not even Gary Carter or Johnny Bench or Piazza, can match Yogi’s durability.

In his seven-year peak from 1950-56 (age 25-31, when his average season was .295/.364/.502 with 27 homers, 108 RBI and 93 runs scored), Yogi just never came out of the lineup. He averaged just shy of 150 regular season games caught per 162 games played in those years. Not for nothing did Casey note that the secret of his success was that he never managed an important game without Yogi behind the plate.

If we count the World Series (which the Yankees played in six times in those seven seasons) and the All-Star Game (which Yogi started each of those years, including catching all twelve innings in 1955), Yogi’s teams played 1,121 games (160 games a year), and Yogi caught 1035 of those (148 per year, not counting spring training). It gets worse: the season usually started later and ended earlier than it does today, and featured lots of doubleheaders—Yogi caught the entirety of both ends of a doubleheader an astounding 117 times in his career.

In the years from 1950-56, he caught at least parts of both ends of a doubleheader 123 times in seven years, an average of more than 17 times a year, and had just 44 days off from catching per year (counting travel days, the All-Star Break, and the break between the end of the regular season and the World Series), meaning that he strapped on the “tools of ignorance” three days out of every four days. In 1954, for example, he caught 150 games in 167 days:

Yet, with all that kneeling and squatting, the kind of workload that routinely led guys like Bench and Roy Campanella to go and have a year hitting .207 now and then, or caused Carlton Fisk to miss a ton of time to injury in his prime, or ground Carter into a broken-down shell by age 33, or sapped Jason Kendall of his bat and his legs by 30, Yogi never had an off year. His worst year with the bat in that stretch was 1955, when he batted .272/.349/.470, drove in 108 runs, won the MVP award and hit .417/.500/.583 in a seven-game World Series. His finishes in the MVP voting those years were 3d-1st-4th-2d-1st-1st-2d.

Measured by OPS+, Yogi was at least 9 percent better than a league-average hitter every year from age 22 through 36, and played at least 120 games (counting the postseason) every year from age 23 through 36. And Yogi was able to swing the bat well enough and move his legs well enough to go on to a few more productive years as an outfielder in his mid-30s after Elston Howard took over the main catching duties. As a part-time player at 38, he still had enough juice left to catch 35 games and bat .293/.360/.497, including .337/.404/545 after July 1. Even if you watched Yogi in his post-playing years, from his days as a manager to his final years as an elderly man, he always walked like a man his age or younger, while most old catchers move like men aged before their days.

Did Yogi ever tire? His batting line suggests otherwise. He didn’t tire in long games—his career batting line in extra innings was .355/.447/.618, in the late innings of a close game .306/.367/.532. He got stronger as the season went on—his career OPS was 802 in the first half, 858 in the second half, and he did his best work in the dog days of July and August (career batting line of .313/.381/.517 in July and .301/.366/.500 in August compared to .247/.312/.402 in April). He had gas left in the tank for October: he batted .274/.359/.452 in 75 games and 259 plate appearances in the World Series (more than anyone else in the game’s history), including .317/.403/.530 with ten homers and 34 RBI in 52 World Series games between 1952 and 1961 (he had an OPS above 1000 in three straight Serieses from 1953-56).

Behind The Mask

Yogi may have had the natural tools of a catcher, but he was very raw when he came to the majors (having mostly skipped the minor leagues to visit France), and labored greatly under the tutelage of Bill Dickey to learn the craft. He had to earn the trust of the Yankee pitchers as well, as this anecdote from 1949 captures:

Berra had some trouble with Yankees pitchers, especially Vic Raschi and Allie Reynolds, who thought he smothered curve balls and stabbed at fastballs, and thus made it difficult to get close calls from umpires. For his part, Stengel did not yet completely trust Berra either. In some critical situations the manager would call the pitches from the dugout, infuriating the veteran pitchers. Finally, one day in a game against the Athletics, Reynolds had enough. Stengel began waving to Yogi to get his attention so he could call a pitch. Meanwhile, Allie warned his young catcher if he looked into the dugout he would cross him up intentionally. Berra knew this was not an idle threat and ignored his manager at the risk of being fined. The incident proved to be a turning point in his relationship with the pitching staff; they now felt that they could trust Berra.

How good a handler of pitchers was Yogi? While the park, the Yankees’ infield and outfield defense, and Casey’s idiosyncratic use of pitching rotations were also major factors, the Yankees in Yogi’s years had a long succession of successful pitchers who were nowhere near as successful with other teams.

What about throwing out base thieves? In his prime years, we see that he consistently caught more base thieves than the average AL catcher:

We only had stolen base data for a four-year period of Yogi’s prime when I compared him in 2009 to the great catchers in terms of 1) his ability to both catch opposing base thieves and 2) an overlooked aspect of a good catcher, his ability to deter them from trying in the first place. Since then, Baseball-Reference.com has added catcher defensive data covering the rest of Yogi’s career, so here I present the chart from that article, with the updated numbers in yellow:

Again, see here for an explanation of the data. Even adjusting for the piteous state of base stealing in the American League of the late 1950s, Yogi was a very tough catcher to steal on. Opponents ran a lot on him between 1948 and 1952 while he was still working on his defense (his success rate against opposing base thieves was poor in 1948-49), but as he turned the corner and started nailing more of them, attempts dropped off sharply and stayed low until he started getting old. Yogi’s ability to cut off the running game in his prime years probably merits him a share of the credit for the high number of double plays turned by the Yankees of the Stengel era.

The Man, The Myth, The Manager

By 1958, Yogi was popular enough to encourage Hanna-Barbera to make him the namesake for Yogi Bear (who is still going as a cartoon character 57 years later). Yogi sued Hanna-Barbera for defamation, but later dropped the suit, proving himself smarter than the average bear animator. The Yoda-like aphorisms that made Yogi a lasting pop culture icon, with their fractured syntax and malapropisms often wrapped around a core of wise observation, are a reminder that he represented a type of man we see much less of in public life today: shrewd, intelligent, but mostly unschooled.

Italian immigrants of Yogi’s day, like his parents, tended to place a higher value on hard work than education, and the former made Yogi a great athlete. But his people smarts were also a big part of his success as a player on perennial champions and as a manager. He was so chatty behind the plate that he frequently distracted hitters, and on teams whose dominant personalities ranged from the frosty Joe DiMaggio to the combative Billy Martin to the sly Whitey Ford to the perpetually adolescent Mickey Mantle, Yogi was their stable center.

Yogi took over from Houk as Yankee manager in 1964, helming a transitioning team with a lot of injury-prone veterans, and led them to their fourth straight pennant in a dogfight. That team was in third place on August 22, five and a half games behind the Orioles and four behind the White Sox after an August swoon, but Yogi had thrown rookie Mel Stottlemyre into the rotation on August 12; he went 9-3 with a 2.06 ERA the rest of the way, and the Yankees pulled the race out by one game, winning 99 games, including doubleheader sweeps on September 22, 23 and 30.

The Yankees being the Yankees, they then unceremoniously fired Yogi after he lost the World Series in seven games, replacing him with the winning manager, the Cardinals’ Johnny Keane. The Yankees would spend over a decade in the wilderness after this, not returning to the postseason until 1976.

Yogi would go on to play again (briefly) for the Mets and coach on the 1969 Miracle Mets. He got his next managing job in 1972 under even more trying circumstances: Mets manager Gil Hodges, just a year older than Yogi, had died of a heart attack on April 4 as spring training was winding down, and the team was suddenly in need of a manager with the season about to start. The schedule was mercifully delayed by a brief work stoppage, but Yogi’s steadying presence helped the traumatized clubhouse focus on the field, and the team roared out of the gate to a 25-7 start before injuries wrecked their season.

The following year, Yogi pulled off another miracle, again with the help of a timely rotation change (George Stone playing the Stottlemyre role). The Mets, in last place entering August 31, won the NL East, upset the vastly superior Big Red Machine in the National League Championship Series (the Mets won 82 games, the worst record ever by a pennant-winning team, while the Reds won 99), and pushed the defending champion “Mustache Gang” A’s to another seven-game World Series loss. The Mets fired Yogi a year and a half later, and would spend over a decade in the wilderness after this, not returning to the postseason until 1985.

Yogi’s final managing gig came in 1984, when George Steinbrenner tapped him to manage the Yankees after firing Billy Martin for the third time in seven years. Yogi oversaw the development of Don Mattingly into a superstar, but that team had highly unreliable pitching (45-year-old Phil Niekro was its only dependable starter), and Yogi was fired just 16 games into the following season, replaced again by Martin. The Yankees would spend a decade in the wilderness after this, not returning to the postseason until 1995.

Yogi got one final coaching job, with the Astros (after turning down an offer to manage them). Houston promptly won the NL West in 1986, his twenty-third postseason appearance in 40 years in an age before the Wild Card, and—amazingly—only the second to terminate short of the World Series. Undoubtedly his memory will be honored at this year’s World Series, whether or not any of it is played in New York. Because nobody worked harder to bring home more World Championships than Yogi Berra.