Muslim spokesman and best-selling writer Reza Aslan clearly thinks Muslims have done and said more than enough to denounce violence in the wake of the January 7 attacks in Paris. He went on television to express his resentment that anyone who would suggest otherwise. “Anyone who keeps saying that we need to hear the moderate voice of Islam—why aren’t Muslims denouncing these violent attacks—doesn’t own Google.”

I risk Aslan considering me a backwards rube, then, in suggesting that moderate Muslims do in fact need to say more to help stem this ongoing tide of violence. He’s right that there have been some good forthright responses. But I’m guessing that many Aslan would include on his long list are less helpful. Some of these have been hamstrung by rigid standards of sensitivity. There’s groups like the Council on American-Islamic Relations, who play a disingenuous shell-game to their benefit, calibrating their rhetoric about violence depending on their audience. Some criticisms of the attacks equivocated even as they criticized. “Yes, the attacks were awful, but…” These people urge us to move on from Paris and focus on Israel and Syria.

How to Reach the Banlieues?

Beyond this, there’s this key question: Whose voices will actually be heard by impressionable young Muslims, like the killers in Paris who grew up in isolated banlieues on the outskirts of French cities? It seems that many young people radicalized in recent years have been influenced not by imams and formal religious channels, but by a mish-mash of global pop culture influences. In a hair-splitting way, then, it’s fair to say that the fruit of this radicalization process is not Islamic per se. The problem is that the perpetrators over and over again believe it to be so.

So whose voices might be heard by young Muslims—in France, throughout Europe, and around the world? More than politicians, clerics, and writers, young people in Europe of all races, ethnicities, and religions follow sports stars. If anything, the trend is more focused in Europe than America. Here, football, basketball, and baseball compete for allegiance. In Europe and most of the world, it’s all football (or soccer, if you will) all the time. The top footballers playing in Europe have a global celebrity power and pull that few others can match. And, since the 1990s, more and more of these footballers have been Muslims. Football—the world’s most popular sport—has been transformed by the involvement of Muslim players.

Realizing this (and being a football fan myself), I started looking hopefully for statements by Muslim footballers following the Charlie Hebdo attacks. I used Google searches (I promise I know how these work), Twitter, and Facebook. But day after day, my searches came up largely empty with a few revealing exceptions. Aslan aside, it seems not all voices have been heard from.

French football did respond collectively. The top French league marked the occasion with appropriately somber ceremonies. The slate of matches following the Charlie Hebdo attacks observed a moment of silence and saw players wearing black armbands. Some players went further, wearing warmup shirts bearing the “Je suis Charlie” slogan seen at the massive January 11 unity rally in Paris showcasing French solidarity.

Like moments of silence, unity marches are heart-warming, but not necessarily convincing or long-lasting. They run the risk of being short-lived Kumbaya moments in part because they’re such a commonplace feature of our contemporary culture. They appeal to sentiment rather than belief, so are less likely to offend. In the aftermath of recent attacks, we need more than this. Forthright statements of disavowal need to accompany displays of solidarity. Unfortunately, there’s been no statement along these lines from any Muslim footballer on record.

Among Muslim Football Stars, a Pattern of Silence

Among those who’ve remained silent are football stars Franck Ribéry, Karim Benzema, and Samir Nasri—each of whom is a Muslim and Frenchman who’s played for the national team. So too the retired Zinedine Zidane, who even now enjoys a star power beyond that of most athletes around the world. He earned this status in part as the star of the 1998 World Cup, which saw France’s multi-racial and enormously talented “rainbow team” win the final and raise the trophy. Zidane’s roots are in Algeria, from where his parents migrated to France before he was born. Around the world, no athlete’s shirt has been cherished by more fans than Zidane’s. Notably, this Muslim global mega-star, too, has said nothing in the wake of Charlie Hebdo attacks.

Some might say (and perhaps these players are thinking) that their job is not to get involved in politics or religion, but simply to help their team win trophies. That’s true to a point, yet it doesn’t take account of their roles as cultural ambassadors for both their European football clubs and for Islam. Many European clubs have been increasing interest in Islamic issues. Some have shown their sensitivity by building separate showers, reserving space for prayer, and changing practices involving alcohol. Bayern Munich is currently constructing a masjid for Muslim players, which will eventually include an Islamic library and full-time imam.

Although racism continues to plague some corners of European football, there’s relatively little opposition to Muslim players specifically. On a couple of clubs, older Muslim players even play a grandfatherly role, and are looked up to by younger teammates—Muslim or not. English children playing football in parks are seen emulating the motions of the Muslim prayer ritual of some of their favorite players who happen to be Muslims—without necessarily understanding these. All this speaks to the wide-ranging effects of multiculturalism in European football among other areas of society.

Is Multiculturalism a One-Way Street?

But is multiculturalism just a one-way street? That’s how it’s often understood—that Europeans should learn about things like Muslim food ways, clothing, religious practices, and values. This is certainly happening, partly due to growing role of celebrity Muslim footballers playing on clubs throughout Europe. But a full multiculturalism would send influence in both directions. It would see Muslim emigrants to Europe, particularly successful ones like professional footballers, come to appreciate and support things like individual freedoms and toleration.

According to media outlets, Muslim footballers have communicated almost none of this since January 7. In fact, only two Muslim footballers have spoken publicly of their opposition to the killings in Paris. Ivorian Yaya Touré, who plays in England, spoke to a reporter a few days after the attacks, but appeared ill at ease doing so. He said he felt sorry for the families of the slain and said that people should be free to “say what they want to say,” but quickly followed up saying that Charlie Hebdo was “trying to do too much, and sometimes they do it not with respect” in their depictions of Muhammad. He also tried to shift the narrative away from the actions of Muslims to non-Muslims’ views of Islam, saying that Muslims now feared reprisals.

Lilian Thuram went further. A native of Guadeloupe, Thuram moved to France as a boy. There he experienced racism, but also developed quickly as a footballer. Eventually, he enjoyed a legendary career for club and country as he joined Zidane on France’s World Cup-winning 1998 national team. Thuram was out of the country at the time of the attacks, but when he learned about them and the unity rally planned, he rushed back to France to participate. “It’s vital that we support the victims and that we don’t sink into fear. To defend society we need to build solidarity,” he explained. Thuram has spent time following his retirement on anti-racism campaigns, and sees similar work needing to be done among young Muslims in France.

There’s One Notable Exception to This Trend

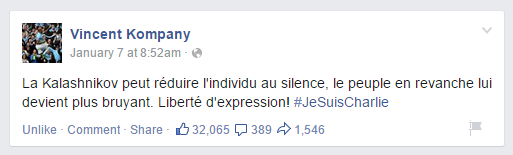

However, the honor for the strongest response by a European footballer to the January 7 killings belongs to Vincent Kompany. There’s a catch, though—he’s not Muslim. Kompany is the son of a Congolese father and Belgian mother, who plays for Belgium’s national team and for a club in England. Like many other star athletes today, Kompany maintains an active presence on social media. Just hours after the Charlie Hebdo attacks, he posted a message to both his Twitter and Facebook page: “La Kalashnikov peut réduire l’individu au silence, le peuple en revanche lui devient plus bruyant. Liberté d’expression! #JeSuisCharlie.” Or in English: “The Kalashnikov silences the individual, but emboldens the masses. Freedom of expression!”

It’s a remarkable and so far unique response to the attacks. Kompany went beyond solidarity to succinctly express his commitment to freedom of expression, pluralism, and toleration. This message is exactly what’s needed today, and it received many likes on Facebook (including mine).

But Kompany’s short statement angered and shocked many of his fans. Some critics said he was focusing too much on freedom of expression and not enough on respect for Muslims. Some urged Kompany to focus his criticism on the actions of Israel and western nations involved in Syria. (“I am not Charlie. I am Palestinian who is being stolen. I am Syria who is being bombed.”) Some questioned his African identity, suggesting he’s a sell-out. (“You should be ashamed of being a slave of white people.” “You worship the white man.”) And some critics told Kompany that he was missing the real story behind the Charlie Hebdo attacks. These respondents were among those who have marked up grainy photos online and claimed that the Charlie Hebdo attack was a Jewish conspiracy orchestrated by Mossad.

These angry responses to Kompany show us why sadly he stood alone among fellow celebrity footballers in his position. They show that humanitarianism–which is always a fragile thing–risks being suffocated by post-colonialist frustrations, aggrieved feelings of disrespect, and deep-rooted anti-Semitism. There are other hopeful exceptions to this concerning pattern, especially the slain Muslim policeman Ahmed Merabets, whose family spoke eloquently after his death, and Lassana Bathilys, the Muslim man who hid Jewish shoppers at the kosher supermarket from the gunman trying to hunt them down. But more humanitarian voices with star power like footballers would help even more. I hope Kompany is right—that the bloodthirsty attacks in Paris will embolden the masses to unequivocally denounce violence and intolerance. But I’d be further encouraged if more of his footballing colleagues, especially Muslims, would join him in this vital project.