Children’s books are a field my wife and I have gotten to know pretty well over the past few years, and it has turned out to be far more important, interesting, and enjoyable than I ever would have guessed.

We haven’t quite made a comprehensive survey of the field, but we have been on the lookout for—and have been the recipient of—a constant stream of books for two very inquisitive young boys. Sherri and I have had the opportunity to sift through a lot of clunkers and to find some books that we truly love, which we love reading to our kids. The best part is that eventually they start reading them back to you.

I’d like to share some of what we’ve learned by offering a list of holiday gift ideas. These recommendations are mostly targeted at kids in the 3- to 7-year-old age range, because that’s what we have, though our oldest is a bit precocious so some of these recommendations might stretch up a few extra years. These selections have been extensively road-tested. They are the stories that have proven their ability to keep the attention of the kids and also be enjoyable for the adults, even the 37th time around. A good story is an end in itself, but many of these books also serve an educational purpose or offer wholesome themes and good values.

There is something else which we regard as just as important as a good story: good illustrations. By the end of the 20th Century, children’s book publishers somehow adopted the premise that books written for 5-year-olds should look as if they were drawn by five-year-olds. I blame Modern art, with its contempt for the technical skill of realistic rendering. We obviously disagree with this approach and think that raising a child on good, realistic illustrations is as important as teaching him to speak proper English.

One of my favorite discoveries in this regard is the original versions of Beatrix Potter’s Peter Rabbit stories. I have seen many versions of the Peter Rabbit stories produced with other people’s illustrations, and I have no idea why anyone would do such a thing. After all, there isn’t much to the stories themselves. What really makes the books special are their superb illustrations.

Before Beatrix Potter was known as an author of children’s books, she made a name for herself as a natural scientist and scientific illustrator. This was back when photography was still new, and the ability to make accurate, detailed, lifelike drawings of plants and animals—she specialized in mycology—was an important skill. This background shows. Her rabbits may be dressed in little coats and shoes and hats, but they are real rabbits. (Here is her live model.)

My favorite version is Peter Rabbit’s Giant Story Book, because it is based exactly on her original versions and the pictures are large and beautiful. The only drawback is logistical: the last page of each of the stories faces the first page of the next story. This can be a problem when you have a two-year old who really loves stories but is supposed to be going to bed. Let’s just say that it would be better if there were a blank page in between.

You can also buy these stories as individual volumes in a boxed set, but I found that the whole series contained some clunkers—some stories that weren’t very good and didn’t engage the kids’ interest (or mine). The “Giant Story Book” has only the best.

Also, for those who are good at adopting funny voices when reading to children, the Beatrix Potter stories provide a lot of scope for giving different voices for the different animals. I particularly like frogs. In my version, Mr. Jeremy Fisher sounds pretty much like Winston Churchill—as performed by Joss Ackland. Stories based on anthropomorphized animals have an interesting effect. It’s not that they make you look at animals differently but rather that they make you look at humans differently, by showing animals doing the same things we do but in different ways. (“Once upon a time there was a frog called Mr. Jeremy Fisher; he lived in a little damp house amongst the buttercups at the edge of a pond. The water was all slippy-sloppy in the larder and in the back passage. But Mr. Jeremy liked getting his feet wet; nobody ever scolded him, and he never caught a cold!”)

Oh, and for adults, “The Tale of Ginger and Pickles” provides some wry commentary on the financial crisis and the perils of excess credit. (“The customers came in crowds every day and bought quantities…. But there was always no money; they never paid for as much a pennyworth of peppermints. But the sales were enormous.”)

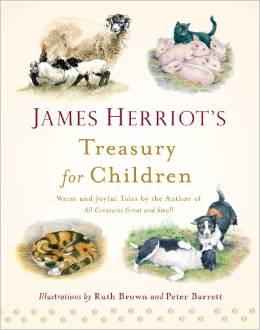

If you and your kids like Beatrix Potter, you will also like the stories of James Herriot. The animals are not anthropomorphized, but they sure do take on a character of their own. Herriot’s “All Creatures Great and Small” books are his reminiscences of life as a young veterinarian in the 1930s working with the crusty farmers of the Yorkshire Dales. His original stories are better suited for kids who are a little older. Aside from a few (very mild) adult themes, some of the anecdotes are a bit too subtle for a five-year-old audience. But I came across a nicely done volume, James Herriot’s Treasury for Children that selects a few of the most appropriate stories—for example, the tale of a lost kitten who adopts a sow as its surrogate mother—and edits them down to slightly simplified versions, while keeping the character of the original stories. The illustrations for the first two stories are a little mediocre, and perhaps for that reason, the rest of the stories have another, much better illustrator whose glowing watercolors capture the beauty of the Yorkshire countryside.

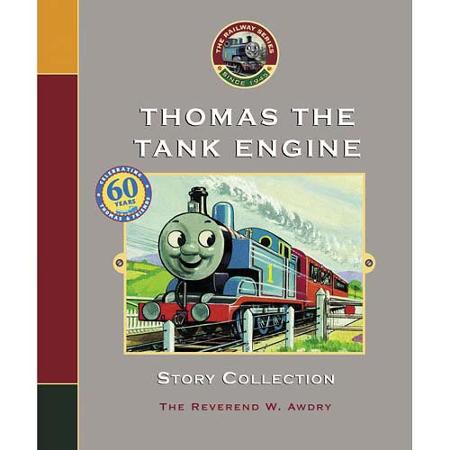

To go from an agricultural setting to an industrial one, I found that I quite liked the “Thomas the Tank Engine” stories. I came to them by way of the television show around 2009, right before they made the transition to computer-generated graphics, back when they still filmed the stories on what must have been the world’s greatest model railway set. I have since found that the television shows are constantly changing. The ones from ten or twenty years ago—when the narrator was the wildly inappropriate George Carlin—are very different from the ones five years ago, which are different from the ones today. But the original stories and their wonderfully colorful, detailed, realistic illustrations stay the same. We got the Thomas the Tank Engine Story Collection, a thick volume with all of the original stories and their original illustrations. Many of the themes are about a child’s version of productivity—listening, staying focused on a task, and being a “really useful engine”—and let’s just say it was a different era when the sooty world of heavy industry was considered an appropriate setting for light-hearted children’s stories.

And yes, in case you were wondering, we are sort of attempting to raise our children in Edwardian England. It seems better than a lot of the other alternatives.

Going from industry to technology, I found an interesting version of Jules Verne’s classic science fiction story Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea. This is a pop-up graphic novel. It has a very compressed version of the story and the quality of the actual illustrations is poor, but the kids are fascinated by the “paper engineering,” including a paper wheel that you turn to open the cover on the observation window of the Nautilus, revealing the eye of a giant squid that is attacking the ship.

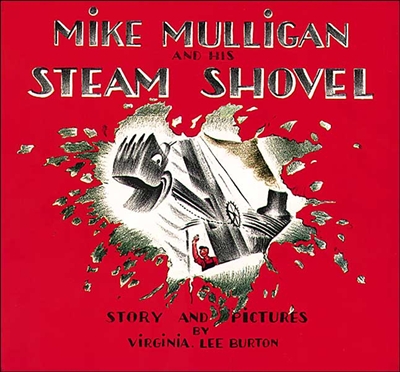

The queen of glamorous industrialization is Virginia Lee Burton whose books feature anthropomorphized machines rendered in Art Deco-inspired illustrations. The best are Mike Mulligan and His Steam Shovel, about an obsolete steam shovel and her owner who find work and a permanent home while digging the foundation for the new town hall in Popperville, and my top favorite, Katy and the Big Snow, about a snowplow whose determination and persistence bring life back to the town of Geopolis after a heavy storm.

For the same reasons, we also liked The Little Red Lighthouse and the Great Gray Bridge, about a small lighthouse apprehensively watching the construction of a giant new bridge above it. The added benefit is that the Little Red Lighthouse is a real lighthouse, which you can visit in a park underneath the George Washington Bridge in New York City.

I don’t choose children’s books with a propagandistic goal in mind, but it sure doesn’t hurt to raise my kids on books from an era when industrialization was still looked on as glamorous and exciting and not as a scourge to be stamped out.

The books I have mentioned so far tend to be from an earlier era, when the themes were more wholesome and the style of illustration was less crude and cartoonish. Another good example is Make Way for Ducklings, a classic with a sweetly told tale about a mother and her ducklings, and fine, skilled depictions of the Boston Public Garden.

But I have picked up a number of books from the later era—the post-Dr. Seuss era. I’ve never been a great fan of Dr. Seuss, not even when I was a kid. The illustrations are too surrealistic and the plots and the language are chock full of nonsense. At it worst, it is Children’s Theater of the Absurd. And don’t even get me started about the Lorax.

But I have found that Fox in Socks, Dr. Seuss’s book of tongue-twisters, is great for a beginning reader who is just starting to take off. Because it contains so many similar words right next to each other—”beetle” and “bottle,” for instance—it requires the young reader to pay close attention and to actually read each word, rather than skimming over it and guessing or trying to recall it from memory. So it teaches a skill of attentive reading that is very important. (When I used to teach writing classes, I found that many young people reach college without acquiring this skill.)

P.D. Eastman’s Go, Dog, Go, which is very much in the Dr. Seuss vein, was very helpful earlier on, when a child is just beginning to speak. It provides silly, memorable illustrations for the meanings of a lot basic words—”up” and “down,” “above” and “below,” and so on—that help to build a young speaker’s vocabulary.

And I’ll forgive Dr. Seuss the Lorax, because he gave us Thidwick the Big-Hearted Moose, which is, believe it or not, a bracing cautionary tale about the evils of altruism.

Cloudy with a Chance of Meatballs has become an over-produced movie franchise with crude, cartoonish computer graphics. I much prefer the original story. The Complete Cloudy with a Chance of Meatballs includes the book’s sequel, Pickles to Pittsburgh. It’s a simpler, quirkier, more focused story about the power of imagination, with illustrations in the style of a realistic 1970s comic book.

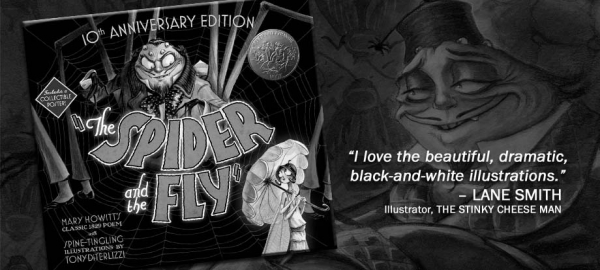

Despite the overall trend toward childish illustrations, there are some very skilled illustrators working today. Tony DiTerlizzi has produced a terrific version of The Spider and the Fly, which pairs the text of the original 1829 poem—a cautionary tale about flattery—with fanciful illustrations inspired by early Hollywood horror films. Much of the text appears in the style of the old dialogue cards from silent movies. But it’s the spider in a smoking jacket and fez that really got me.

I can’t let a list like this go without mentioning Guess How Much I Love You. It’s an amusing, touching, well-told little story and particularly good for bedtime. But let’s face it. There’s really only one reason you buy it: to hear your three-year-old tell you, “I love you all the way to the moon and back.” Which is totally worth it.

When not raising my kids in Edwardian England or early 20th Century industrial America, I’m giving them a good dose of Ancient Greek civilization.

Some years ago, Barnes & Noble printed a good version of Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, with the story retold in simplified form and accompanied with big, colorful, realistic illustrations. That version seems to have disappeared, which is a shame because ours has been loved to death and the binding has come off. But there appear to be a number of others available.

In reading Homer to our kids, we emphasize the Odyssey, and we bowdlerize some of the scarier or more violent passages. One of the virtues of the stories I’ve mentioned above, by the way, is the general lack of violence. I’m not the kind of pacifist who thinks that children should never be allowed to hear violent stories, as if this will somehow prevent them from discovering violence on their own. But when you have two boys, there is always a base level of violent energy, and you don’t want to ratchet it up any higher. My kids love the battle scenes in the Iliad, but this can result in young boys throwing broomsticks at each other, pretending they are spears.

In the Contest of Homer and Hesiod, I side with the judge, Paneides: Homer is brilliant, but “he who called upon men to follow peace and husbandry should have the prize rather than one who dwelt on war and slaughter.”

So why include Homer? Partly because I want my children to have a base of knowledge of Greek civilization and mythology, but also for one other really important reason: I want them to grasp the difference, in Homer’s two stories, between two different kinds of heroes. There is Achilles, who wins by being the strongest and the toughest—and then there is Odysseus, who wins by using his mind to outsmart his opponents. Reading these stories really helped them to get the concept of a hero who uses his mind to solve problems, and to get it in a way that only a vivid story can convey.

As more general background on ancient Greece, I like A Child’s Introduction to Greek Mythology. The illustrations are more crude and cartoonish than I would like. My usual standard for Greek mythology is that the illustrations should be at least as good as Ancient Greek vase paintings, or else the artist is basically saying that we’ve made no artistic progress in 2500 years. (You might be surprised at how many books fail this test.) But I still like this book because it gives a comprehensive overview of all the gods and heroes and all the important stories, on a level that my kids understand and find interesting.

Like I said above, I’m not using my kids’ books as propaganda. For example, I am not directly or explicitly raising my kids to be atheists like me. But I do want them to be aware of a whole variety of myths from different cultures so that they will have open minds and broad horizons, realizing that many people have believed many different things. As they get old enough to start noticing these issues—my oldest is just at that stage now—I want them to be able to relate Christian mythology to other mythologies and note the parallels. Later on, they will be ready to draw their own conclusions.

(More recently, a friend of mine sent me a couple of comic book versions of episodes from Indian history and myth. They don’t seem to be easily available, but the one my boys liked best is Paurava and Alexander, the story of Alexander the Great’s attempt to conquer India and the king who stood in his way. I think my kids liked it because it connects Indian history to the Greek history they were already familiar with. Plus, you know, it’s about war.)

When I want better illustrations, I turn to Peter Connolly, whose is very well known to history buffs for his illustrations that reconstruct the ancient world based on the best archaeological evidence. I recently found The Legend of Odysseus, which provides a brief retelling of the story of the Iliad and the Odyssey with historically accurate illustrations, interspersed with sections on the archaeological discoveries about Minoan and Mycenaean civilization and the ruins of Troy. Those sections are a little beyond my kids’ grasp at this point, but it is something that they will be able to grow into, getting more and more out of the book as the years go by.

When it comes to educational books, there are a couple of series by major publishers that are quite good. Usborne’s “See Inside” series, such as See Inside Ancient Rome, are uniformly good, with bright illustrations, descriptive text, and little flaps that lift up—which little fingers are very eager to do—to provide more information. This is one of those big publishing franchises where you can pick out a book on just about any topic and find that it is done well.

Another is Maurice Pledger’s “Explore” series—such as Explore Underwater—which are based on very good, realistic illustrations of animals accompanied by interesting scientific facts. And, of course, lots of little flaps to lift up.

Then there is the vast empire of DK photograph books. More sophisticated versions provide visual guides to a certain kind of technology or era of history, but DK also makes a very useful series of board books for very young kids (the kind with stiff cardboard pages that handle a lot of abuse) which feature words and photos that teach basic concepts and vocabulary. I nearly lost my voice once by having my son point to pictures in an animal board book. Sherri would say the name of the animal—and I would be required to make its sound, to delighted giggles from my audience.

An early favorite was the Big Book of Things That Go, a comprehensive index of vehicles. Amazon lists this as being for kids from 5-8, which is probably right if you expect them to read it themselves. But mine practically had this book memorized when they were three.

These franchises are widely available and can be found at any bookstore. But a few of our favorites are rare and out-of-print books that we stumbled across at used book stores or book swaps at school.

One of Sherri’s favorites is Grand Constructions by Gian Paolo Ceserani and Piero Ventura. This gives her a lot of good opportunities to talk about her fields: architecture, construction, and the history of architecture. The text gives an accurate and accessible history of great buildings, and Ventura’s watercolors, often drawn from vertiginous aerial perspectives, are stunning. I found a few other books by the same pair, Marco Polo and The Travels of Livingstone.

I also came across a couple of items from a “Cornerstones of Freedom” series by Weekly Reader. The Story of the Pony Express is great for a couple of boys who are very interested in cowboys, and since we’re close to Charlottesville, Virginia, we like The Story of Monticello.

It looks like many more entries in this series can be found on eBay, though some are too overtly political, including “The Story of the Great Society” and “The Story of Rachel Carson.” Oh, there’s a story there all right, just not the one they are likely to tell. Clearly, the series editor was a modern “liberal,” though I did not find that this affected the stories I’ve read.

At this age, I avoid any detailed political themes beyond very general ideas about how freedom is good and the government shouldn’t have too much power. The main point of these history books is to introduce my kids to what you might call the American mythology, the famous stories about our history.

Since I live in Virginia, some of these have good local connections. Jack Jouett’s Ride is excellent in its own right, with stylized illustrations inspired by old wood-block engravings. Jack Jouett is the “Paul Revere of the South,” who rode overnight from Cuckoo Tavern to Monticello to warn Governor Jefferson, Patrick Henry, and other Virginia legislators about the approach of Banastre Tarleton’s dreaded Green Dragoons. This is of special interest to us because it happened (literally) in our front yard, which is along Tarleton’s route.

I hear folks up in Boston had a little something to do with the American Revolution, too, and I found a very good book about the Jack Jouett of the North. Christopher Bing has created a wonderfully illustrated version of Longfellow’s The Midnight Ride of Paul Revere. The beginning and end of the book include maps and reproductions of original documents that give the true story, since Longfellow, being a poet, took a little license. This is another one of those books that my kids will get more out of as they get older. And since Paul Revere is a little more famous than Jack Jouett, this book seems to have the advantage of still being in print.

Another good piece of historical leged is the story of Christopher Columbus. We found a nice illustrated version of The Log of Christopher Columbus, which consists of carefully chosen excerpts from Columbus’ log of his first voyage to the New World.

Most of these books, though out of print, are easily available from used booksellers on the Internet. One that seems to be particularly hard to find, though, is one of my favorite stories: Everyone Knows What a Dragon Looks Like. This book is out of print but seems to be what you would call a “cult classic.” At every site that mentions it, the comments are full of testimonials from readers saying how much they loved the book as a child. If you want to buy it, though, don’t go here, since the most readily available version is a knockoff reprint in which the color illustrations have been shrunk and turned into black-and-white. Try eBay instead.

Told in the style of a Chinese folk tale, this is a very nicely written story about the city of Wu, which is about to be invaded by the Wild Horsemen of the North. The Mandarin confers with his top advisors, the Chief of the Army, the Leader of the Merchants, the Wisest of the Wise Men, and so on. They decide to pray to the Great Cloud Dragon to save them. The next day, an old man shows up at the city gate claiming to be a dragon, and the gate sweeper takes him to the Mandarin. There follows a very amusing scene in which the Mandarin and his advisors declare that “everyone knows what a dragon looks like,” and proceed to give dragons all of their own characteristics. The Mandarin thinks dragons look like mandarins, the wise man thinks they look like wise men, etc. (In my telling, of course, each of these characters has a very distinctive voice.) After the old man is rebuffed, it remains for the poor, orphaned gate sweeper to keep an open mind and treat him politely.

It’s a nice little story about not judging a book by its cover, so to speak. It also provides a message that gets repeated pretty often around our house—perhaps a little more often than our kids would like: “If you want a dragon to help you, you must treat him with courtesy.”

Since this is the Christmas season, I’ll end with a few recommendation of Christmas stories.

How Santa Got His Job is a quirky, humorous narrative describing the various jobs Kris Kringle held down which prepared him for his eventual occupation, such as his job as a chimney sweep, where he was so adept at going up and down chimneys that he never got dirty, causing him to be fired because he was so clean no one believed he had actually done anything. You get the idea.

The more traditional depiction of Santa Clause is from Clement C. Moore’s poem “The Night Before Christmas,” which has spawned numerous variations. We have “The Hillbilly Night Afore Christmas,” which requires a little deciphering of the language and some work on the accent. This is part of a series that seems to ring every possible variant, like “The Cowboy Night Before Christmas.” But they aren’t just cheap knock-offs. There’s some real creative thought that goes into adapting the original poem into different cultural contexts.

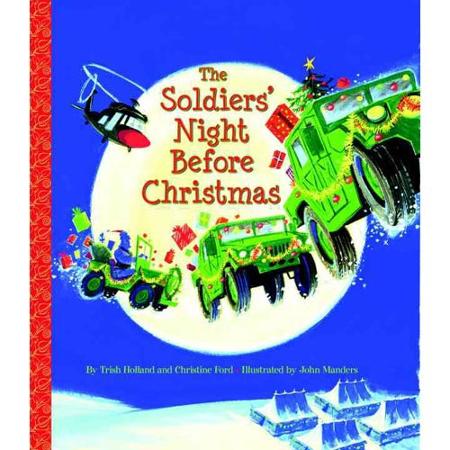

My favorite variation on “The Night Before Christmas” is The Soldier’s Night Before Christmas which depicts homesick soldiers at a base in the Middle East waiting for a visit from “Sergeant McClaus.”

But nothing quite matches the original. A few years back, Barnes & Noble produced a version of Clement C. Moore’s poem, illustrated by Niroot Puttapipat in a very Victorian cut-paper technique, with a spectacularly detailed pop-up finale. We saw it on sale a number of years ago and wisely bought two copies—one to be sacrificed to the toddler years, and another to fall back on now that our kids are a little less destructive. This is the last story we read before bedtime for the weeks between Thanksgiving and Christmas. I like the old-fashioned formal language and rhyme structure of the poem, and my kids are so impressed that they are talking about making a book of their own in the cut-paper style, which is an excellent Christmas project with mommy.

Of all the gifts you can give your children, the most important is the time you spend with them opening up their mind to a love of stories, of words, of reading, of history, of art. In giving them these things, you are giving them the whole world.

These are the books that have helped us explore the world with our boys. I hope you have the opportunity to enjoy some of them, too.

Follow Robert on Twitter.