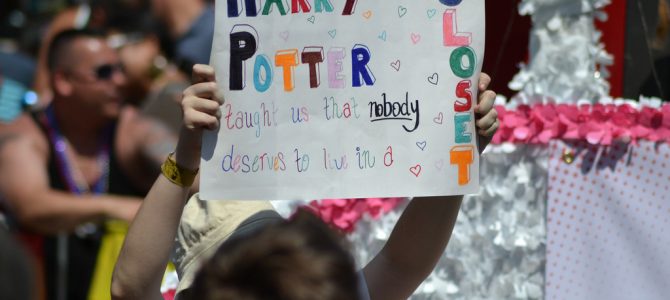

Friends, I urge you to unite with me in opposing one of the greatest threats to the future of our republic: the massive overuse of Harry Potter references in political discussion. Stuff like this.

We don’t need a special prosecutor. We need an Auror. @jk_rowling

— Joss Whedon (@joss) May 9, 2017

In J.K. Rowling’s children’s books, you see, “aurors” are good wizards specially trained to hunt evil dark wizards, and Donald Trump is just like a dark wizard, get it?

Oh, never mind.

This sort of thing has got to stop. We’re drowning in it. It has even spawned a counter-meme, in which someone cites Harry Potter and gets the reply, “Read another book.” Or as one wag recently put it, “I’ve never read any of the Harry Potter books, so I am unqualified to comment on political goings-on.”

It doesn’t stop with Harry Potter. Consider the way the Left culturally appropriated recent Star Wars films, adopting “the Resistance”—a recapitulation of the Rebel Alliance in the franchise’s latest manifestations—as a grandiose name for their political opposition to Trump. Throw in a handful of other popular books, television series, and movie franchises—”The Hunger Games,” the Avengers, and so on—and our politics is being overwhelmed by pop culture references aimed at children.

This isn’t doing anyone any favors. It contributes to making our politics glib, emotion-driven, over-simplified, and posturing. At the same time, it takes beloved childhood stories and politicizes them in a way that narrows and diminishes their meaning.

Let me be clear that I’m not complaining about this because I dislike or look down on these pop-culture movies or children’s books. I loved “Star Wars” when I was a kid, and I basically wanted to be Han Solo. I was too old when the Harry Potter books were published to be in their target age group, but I have discovered them with my kids, and they are clever, well-crafted stories that convey a lot of good values.

But in order to be pitched at a child’s level—or on the elemental, mythic level “Star Wars” aimed for—the conflicts that drive the plots have to be relatively simple, obvious, and generalized. Did the guy with the scary-sounding name kill your parents? Well, then it’s pretty obvious he’s the bad guy, and we can just go from there. Did the guys in the Nazi-style uniforms blow up a planet just to make a point? Yep, they’re evil.

There’s no need for philosophical speeches, complex policy discussions, or a balanced consideration of opposing viewpoints. Put in references to galactic trade policy and you’ll just annoy everyone. And it’s fine that you can’t do any of these things, because nine-year-olds aren’t ready for it. Nor is the audience for a tentpole summer blockbuster.

It’s no coincidence that the villains in the Harry Potter and Star Wars franchises bear a clear resemblance to the Nazis. They’re following the Indiana Jones rule that Nazis make a perfect standard-issue villain: clearly evil, instantly recognizable, uncontroversial—and non-partisan. You might not know it to hear some of today’s fevered rhetoric, but Republicans hate Nazis, too.

Yet that indicates the limits of invoking these stories in adult discussions of politics. The moral themes of these franchises are broad, simple, and general, but they’re also a little vague and simplified. You can certainly draw political analogies from them. The problem is that you can draw too many analogies.

I could compare Democrats to the bumbling and ineffectual Ministry of Magic, or point out that they are often on the side of the Empire rather than for the Republic. Or that Han Solo would absolutely be a pro-blaster-rights libertarian. I mean, can anyone deny that? People who don’t share my politics could draw different analogies. The themes are so broad and universal that many different messages could be read back into them from an adult context.

But that’s not their purpose. In the minds of their young readers, stories like this establish a basic sense about the need to choose between good and evil—but it’s only a foundation, and detailed questions about what exactly is good and evil in the real world and how you tell the difference, let alone how this applies to the individual mandate or insurance coverage for pre-existing conditions—all of that is left for later, as it has to be.

That’s why it’s such a disservice to this literature to try to use it as a weapon for scoring points in the political conflicts of the moment. It takes themes that are universal and timeless and makes them merely partisan and topical. I don’t begrudge someone like Joanne Rowling having her own personal political opinions, but I suspect she would want her work to have a life far beyond those opinions—that she would want new readers to discover the Harry Potter novels 20 years from now or 100 years from now and to be able to enjoy them without knowing a thing about the Trump administration.

By the same token, taking these simplified themes from children’s stories and appropriating them for political use encourages the laziest kind of thinking about politics. The whole point of characters like Lord Voldemort or Darth Vader is that you don’t need a lot of deep thought or an adult context of knowledge to figure out that they’re the bad guys and your heroes are the good guys.

But in the real world, it does take thought and knowledge. It requires careful observation, a willingness to listen to detailed arguments by both sides, and perhaps some philosophical speeches. If you develop the habit of using children’s fiction as your template for political debate, you’re not going to bother with any of that. Instead, you’re going to act on raw, elemental emotions rather than rational deliberation. It encourages precisely the glib, partisan, screechingly un-thoughtful politics we have today.

The irony is that in my lifetime, I’ve gone from seeing stories like “Star Wars” sneered at by cultural elites for their childishly simplistic narrative of good versus evil—back in the 1980s, Robin Williams did a stand-up bit where he lampooned President Reagan as “Obi-Ron Kenobi”—to seeing those same stories embraced by the elites because a childishly simplistic narrative of good versus evil is precisely what they’re looking for.

The double irony is that, as a fan of Ayn Rand’s ideas and fiction, I’ve had many people dismiss her work as adolescent, unsophisticated, and unworthy of being included in a serious discussion of important political issues. A lot of those same people have now adopted Harry Potter, Star Wars, and cartoon superheroes as their go-to political analogies. Say what you will about Ayn Rand’s novels, but at the very least they addressed adult political themes head-on, and included actual philosophical speeches about human nature and the role of government—ideas a lot more sophisticated than “may the Force be with you.” Yet here we are today, when the novel with long philosophical speeches is considered too “adolescent,” but the stuff with wizards and dragons and ray guns is the height of sophisticated discourse.

So yes, maybe it is time to read another book. I won’t object to the odd Star Wars or Harry Potter reference in passing—I’ve done it, too—but if you find yourself falling back on it more than once or twice, it’s time to make yourself stop. If these stories mean something to you, use them as an inspiration for doing the adult-level thinking about what is good and right and prudent, not as a substitute for it.

Follow Robert on Twitter.