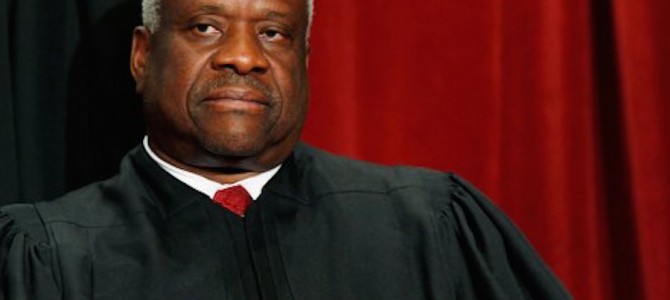

As someone who had the privilege of clerking for Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas, I am more familiar with his opinions than most people are. I read them one after another as I nervously prepared to interview for the position.

With each opinion, I became less confident that I could even carry on a conversation with the man who had written so thoughtfully and prolifically about the original meaning of the Constitution, let alone help him with his work. But one does not have to have read the Thomas canon to know that Jeffrey Toobin’s recent article in The New Yorker, “Clarence Thomas’s Twenty-Five Years Without Footprints,” is nonsense.

Majority Opinions Depend on Seniority

Toobin suggests Thomas has had little or no effect during his time on the Supreme Court because Thomas has written few landmark majority opinions. That argument is deeply misguided. The measure of a justice has nothing to do with the number of 5-4 opinions he writes for the Supreme Court.

The chief justice, or the most senior justice in the majority, assigns the writing of an opinion. It should thus come as no surprise that the assigning justice often chooses to keep the writing assignment for an important or controversial case. Nor should it come as any surprise that, even when the assigning justice chooses not to keep an opinion assignment, he may privilege seniority in making the assignment to another justice.

Toobin’s own examples prove the point. With only one exception, in each of the cases Toobin cites as examples where Thomas joined, but did not write, the majority opinion, a more senior justice in the majority wrote the opinion. Shelby County v. Holder was written by Chief Justice John Roberts, District of Columbia v. Heller was written by the late Justice Antonin Scalia, and both Citizens United v. FEC and Gonzales v. Carhart were written by Justice Anthony Kennedy. The lone exception is Bush v. Gore, which was decided by a per curiam opinion that did not identify its principal author.

Toobin’s conclusion from these cases that former Chief Justice William Rehnquist and current Chief Justice Roberts did not “trust” Thomas to write an important majority opinion is nothing more than armchair psychology divorced from the facts.

Clarence Thomas Has Already Deeply Affected Law

The fact of the matter is that Justice Thomas has written an enormous number of influential opinions at the Supreme Court. Some of those are majority opinions that have not hit the headlines, but have nevertheless had a significant impact on federal law. Others are separate writings that lay out his unique view of the legal provisions at issue. In the tradition of some of the great dissenters—John Marshall Harlan, Antonin Scalia, and William Rehnquist—Justice Thomas does not join opinions with which he disagrees to obtain a result he prefers. He views his oath as requiring more than that.

As even Toobin is forced to concede, Thomas’ separate writings have left a deep imprint on the law. Some have become majority opinions over time. Toobin mentions Thomas’ opinions in Printz v. United States and McIntyre v. Ohio Elections Commission as laying the groundwork for landmark cases on gun rights and free speech limitations on campaign finance regulations.

But one could also point to Justice Thomas’ concurrence in White v. Illinois as laying the groundwork for Justice Scalia’s majority opinion in Crawford v. Washington, which returned to the original understanding of the clause guaranteeing a defendant’s right to confront the witnesses against him, or Justice Thomas’ concurrence in Apprendi v. New Jersey as laying the groundwork for his majority opinion in Alleyne v. United States, which held that a jury must find any fact that increases the mandatory minimum sentence a criminal defendant faces.

Other separate writings have not yet become majority opinions, but have shaped the scholarly debate and influenced countless young lawyers. One such writing—Justice Thomas’ concurrence in United States v. Lopez, which explains that the Commerce Clause is not a bottomless font of congressional power—served as a central feature of the campaign that brought Mike Lee to the U.S. Senate and constitutional interpretation once again to the fore of public debate. By any fair assessment, Justice Thomas’ opinions have had a significant effect on the law.

Perhaps recognizing as much, Toobin pivots to painting Justice Thomas as a “radical” for trying to understand the original meaning of provisions that establish the basic structure of our government and identify some of our most fundamental rights. Perhaps Toobin is right. Perhaps in this day and age, a belief in applying the law as written—divorced from the preferences and predilections of the age—makes one a radical.

If so, count me as a “radical” too—a radical for the Constitution. The document is one of this country’s greatest triumphs. Disregard for it has led to some of our country’s greatest failures. If Toobin is right, and a desire to adhere to the Constitution will lead me, like Justice Thomas, to the “distant fringe” of the legal profession, that’s fine. There is no one whose footprints I would rather follow.