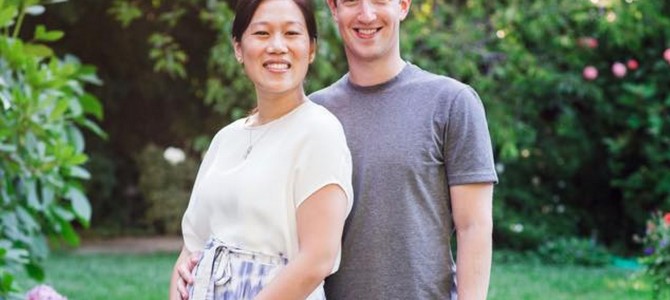

In announcing their current pregnancy, Facebook cofounder Mark Zuckerberg and his wife Priscilla Chan also revealed they’ve had three miscarriages in their attempts to bear children. Miscarriage, although often not discussed, is a part of many women’s lives, given that studies show it occurs with between 10 and 25 percent of known pregnancies.

Here’s part of their announcement:

You feel so hopeful when you learn you’re going to have a child. You start imagining who they’ll become and dreaming of hopes for their future. You start making plans, and then they’re gone. It’s a lonely experience. Most people don’t discuss miscarriages because you worry your problems will distance you or reflect upon you — as if you’re defective or did something to cause this. So you struggle on your own.

In today’s open and connected world, discussing these issues doesn’t distance us; it brings us together. It creates understanding and tolerance, and it gives us hope.

When we started talking to our friends, we realized how frequently this happened — that many people we knew had similar issues and that nearly all had healthy children after all.

We hope that sharing our experience will give more people the same hope we felt and will help more people feel comfortable sharing their stories as well.

We took this invitation to heart, and invited senior contributors to The Federalist to share their thoughts and feelings about miscarriage.

It Can Be Hard to Mourn a Person You Didn’t Know

Rachel Lu

I think pro-lifers find it really hard to figure out how to think about this. Their instinct is to affirm their love of life by making a lot of it, and most of the pieces I’ve read on miscarriage underscore this point. “This is a huge deal, we should be talking about it more. Treat women who have miscarried like any other person who just lost a child.” That sort of thing.

I have experienced miscarriage. For me, it was sad but not wrenching. I am not saying this is the correct way to feel about it, but I also don’t think it’s wrong. Lots of factors will affect the way we feel about a miscarriage. Had you been desperately hoping for a child for years, or was this a surprise, “Wow, was I fertile already?” pregnancy? How far along were you? Is there any reason to think it would be hard to get pregnant again? These things do make a difference, emotionally. Some miscarriages are absolutely wrenching. But if you already have children, and expect to have more, it would be strange to grieve an early miscarriage the way you would the death of an already-born child.

People are sometimes upset by that point, because they think it calls into question the humanity of the newly-conceived. But it doesn’t. Metaphysically, I absolutely believe that everyone is a human being, precious in God’s sight, and fully worthy of love and protection, from the moment of conception.

But people die all the time, and our reactions to those deaths aren’t determined by the metaphysical status of the deceased. They’re mostly determined by our personal relationship to the deceased, and most especially by whether or not we love them. Can we love someone we don’t really know? Maybe a little, but it’s not the same love we feel for a known person. Especially in the early weeks, before we’ve even felt them moving, we don’t really know our unborn children at all. That’s one of the things that makes miscarriage confusing: we know that the person existed, but we didn’t know them, and we don’t even have any mementoes except maybe a grainy ultrasound photo.

Of course, it doesn’t follow that we should blow off a miscarriage like it’s nothing. Even if we didn’t know them, they’re still our own children. The knowledge of their very brief existence does mean something to us, and it should. But for me, both as a Christian and as someone who sees openness to life and fertility as an intrinsic part of womanhood, I find miscarriage to be a bit bittersweet. Death is part of life; it’s sobering to reflect that my own body can be the cradle of both. I also think it’s rather beautiful to reflect that there are souls that pass through life without really experiencing (so far as we can tell) pain or grief. I believe that God cares for those souls in some good and loving way.

One reason I don’t announce my pregnancies early is because, should I miscarry, I really don’t want a lot of people bringing me flowers or meals, or trying to “talk about it.” I never needed or wanted that. Some people do, and that’s fine. But I also think there are probably people for whom pro-life “miscarriage awareness” is more burdensome than helpful. For example, some women name their miscarried babies, do things to observe their would-be due dates or the anniversaries of their deaths, etc. If that gives people comfort, they should do it. But I don’t think we should view such measures as expected or necessary.

What Gives Me Peace about My Miscarriage

Jayme Metzgar

One of the hardest things about a miscarriage (besides the obvious loss) is not really knowing how handle it socially or emotionally. This is compounded by the fact that not every pregnancy loss is identical. Circumstances really do make a difference: whether you’ve been struggling with infertility, whether you already have children, how far along you are, and your own temperament. As women, we tend to compare our experience to others’ and feel conflicted: Am I taking this too hard? Or not hard enough?

Of course, every human life is equally precious—that’s not in doubt. One burden women shouldn’t have to bear is that of validating our child’s humanity through our grief. If there’s anything pro-life people believe, it’s that the feelings of the mother don’t determine the value of the child’s life. He or she is valuable as a human being created in God’s image, period. Our feelings don’t make them any more or less so.

But as finite people, relationships and proximity do impact our grief. With losing a child already born, the grief is both for a loss in the present (who the child is now, and the relationship you have), and in the future (who the child will be, and the hopes you had for him or her). With a miscarriage (especially an early one), the loss belongs much more to the future. Of course, those struggling with infertility experience another set of painful losses and fears. There’s no one-size-fits-all way you’re supposed to feel. We women should give ourselves permission to experience whatever emotions come without expectations or comparisons.

Eleven years ago, I miscarried my third pregnancy in the second trimester. I was 16 weeks along when it was discovered, but the baby had died at around 14 weeks old. So having gone through the whole first trimester with all its discomforts, and having had several months to think about the baby and prepare for his or her arrival, it was hard. I really did appreciate the friends who sent flowers and cards—I was grateful to them for acknowledging the depth of the loss.

Most of all, I appreciated hearing from other women who had experienced a later miscarriage (and there were more than I had realized). One of the hardest emotions for me at that point was wondering if I had done something wrong to harm the baby. I had a lot of guilt and doubts, and they helped me work through those.

We did a few intentional things to memorialize our baby and bring closure, and that helped a great deal. That’s another ache of miscarriage: there’s no tangible evidence or real memories of the child to hold on to. It’s an empty feeling. So, first, we named the baby. My husband also put a memorial stone in our garden and planted a tree nearby. And I wrote a poem for the baby, which in a strange way was probably the most healing thing for me at the time. Of course, the very best thing for my healing was getting pregnant a few months later. Having that next baby (who wouldn’t have been conceived if her sibling had been born) was what really took the sting away. If I’d never had another child, it’s likely I’d still be grieving.

As it is, I can’t say I’m still grieving or that it’s painful anymore. I still remember and love my baby, but I’ve come to have complete peace that he or she was always meant for heaven. My little girl who came next is the one who was meant for me to have and raise. It’s not that my daughter is more valuable than the baby I lost—it’s just she’s the one who’s supposed to be here.

I’m sure there are women who are still grieving for babies they miscarried years ago. I don’t fault them. I also don’t fault myself for not feeling that sting still today. I’m thankful for the support of friends and family through our time of loss, and I’m especially thankful for my Christian belief that death is not the end. One day, I’ll finally get to meet my little one, and heaven will be that much sweeter.

Why Is Miscarriage Still Taboo?

Nicole Russell

“This isn’t a viable fetus,” my doctor said to me. “Let’s schedule a day for you to come in.” At eight weeks along, I’d just found out I was pregnant barely two weeks prior. It was unexpected, sure—my youngest son then was around one year old—but my husband and I were adjusting to the idea and getting excited about it. I’d had a great first pregnancy and couldn’t wait to see what carrying my second child would be like. What gender? What color hair would the baby have? What kind of name goes well with “Beckett?”

I had to ask my doctor again. “What do you mean, not viable?”

Turns out that means you will never know the answer to those questions because you either are in the process of having, or will in a matter of days have, a miscarriage. Upon bloodwork and tests showing the baby had stopped growing, I opted to have a D&C, rather than wait to miscarry naturally. The procedure is relatively simple and recovery is easy, except that you feel a mix of emotions afterward: sadness, emptiness, confusion, and even a bit of shame. My doctors never discussed anything with me except the physical signs of miscarriage I may experience again.

I say shame because what struck me most about having a miscarriage is the fact that it’s so common. Except you would never actually know it’s common, because it feels like it’s still rarely discussed among women (although a Google search will show a myriad of articles on the topic.) According to the March of Dimes, 50 percent of all pregnancies end in miscarriage, many of these before a woman even realizes she’s pregnant. About 15 percent of known pregnancies end in miscarriage.

It’s a hush-hush subject, an awkward topic that people react strangely toward, somewhere between the way you feel when someone tells you she wants to get pregnant and can’t and when a relative has died. How does one react to that news? No one knows, so no one does, and so no one tells anyone. You feel at once lonely, like your friends have betrayed you, sad, like your emotions have betrayed you (crying for a baby you never met?), and angry that your body betrayed you, as it begins to expel what is “not viable.” You find yourself googling: Causes of miscarriage. Could I have done anything different?

Unlike many women who endure a miscarriage, I had a lively red-headed boy to distract me, to propel me into the days ahead. I had friends who rallied around me (brownie bites always taste great, but especially when you’re sad), and emotions and hormones that stabilized over time. My body healed and adjusted, too. Several months passed, and I became pregnant again. Nine months later, all my questions were answered: Girl. Strawberry blonde. Keira.

Every woman’s story about miscarriage is different. For some who struggle to get pregnant, miscarriage is a devastating loss, a baby that mom names, buries, and grieves over. For others, it somehow feels a little less hard, the pain not quite as searing, although I wouldn’t say it’s ever easy. Most miscarriages cannot be prevented through medical intervention or lifestyle changes. They happen because of chromosomal abnormalities or other things about which mom-to-be can do little.

But what should be happening is conversation. Every woman should feel comfortable talking about this painful and uncomfortable experience. In 2015, miscarriage shouldn’t be so taboo. If you have a friend who recently suffered this loss and you don’t know what to say, just admit you’re at a loss, ask her how she’s feeling, and give her a hug. A few words and a little empathy can go a long way, and can ultimately make a common occurrence less taboo, a sad reality a little more bearable.