Whoever carries the Republican establishment’s flag into the 2016 presidential elections—whether Jeb Bush, Chris Christie, or anyone else—must propose a foreign policy different from the essentially bipartisan approach of the past hundred years. This approach has diminished America by disconnecting ends from means while combining “the unbridled tongue with the unready hand.” The American people demand something else. There is no sign the Republican establishment understands what legacy it would have to overcome.

The standard Republican campaign on foreign policy—vows to stand strong against our enemies and to assert America’s leadership in the world—will not restore to Republicans the presumption of superior national security stewardship. That is what Ronald Reagan had earned with his approach to the Cold War: “We win, they lose.” But Reagan was a rebel whom the Republican establishment tried to crush before he came into office, stymied while in office, and whose legacy it erased when he left. Rather, ruling-class Republicans will have to explain why we should expect from them other than what Richard Nixon, Gerald Ford, and the Bush dynasty gave America before and after Reagan.

Speaking loudly while whittling down the capacity to back up words has been the hallmark of our bipartisan foreign policy. Since circa 1900, the Republican mainstream, confused with the rest of this country’s ruling class, has led America increasingly into commitments bigger than the capacity and will to fulfill them—that is, into insolvency. If one were to distinguish a peculiarly Republican component out of this bipartisan compote, that component would be even heavier in words and lighter in the means to effectuate them than its Democratic counterpart. Republican words have been bigger, and the means they have deployed have been even more impotent.

Such as Jeb Bush and Christie are sure to talk “tougher than thou” on foreign policy. Their challenge will be to show how they would actually return U.S. foreign policy to a solvent balance it has not enjoyed for a century.

How the Elites Eroded U.S. Power

Theodore Roosevelt’s “speak softly and carry a big stick” had summed up the solvent foreign policy that America had practiced since the days of John Quincy Adams: keeping America’s peace and winning America’s wars. But Elihu Root, TR’s own secretary of State, won the 1912 Nobel Peace Prize for having convinced America’s bipartisan elites to focus foreign policy on bettering mankind. His chosen tool was a set of impotent arbitration treaties. By 1916, when Republican Charles Evans Hughes nearly beat Woodrow Wilson for the presidency, TR’s view of foreign policy had become a minority view among well-bred Republicans. In 1921, Secretary of State Hughes conceived a set of treaties that have typified American foreign policy into our time: an arms-control deal that reduced U.S. naval forces in the Pacific below those of Japan and committed the United States to not fortify our bases there, while at the same time promising to uphold the independence and territorial integrity of China. Republican and Democratic elites were sure that Hughes had ensured peace. In fact, he had paved the way for World War II.

Post-war “containment” was the Democratic and Republican establishments’ compromise. But neither managed to prevent the Communist world from breaking out of it, first in China, then in Korea, southeast Asia, Cuba, Afghanistan, Angola, Nicaragua, etc. Establishment Republican Secretary of State John Foster Dulles cut arguably the most pathetic figure with his declaration that he would retaliate “massively” (i.e. with nukes) against communist breakouts “at times and places of our own choosing.” Sen. William Fulbright (D-AR) punctured that pretense by asking for an example. Dulles had none.

Barry Goldwater, however, had one. Channeling Douglas MacArthur, who had actually won a war, Goldwater said that if we were going to oppose Communist aggression in Vietnam we should use all we had utterly to destroy the enemy, or we should not fight at all. But Goldwater, too, was a rebel against the Republican establishment. It labeled him a primitive warmonger, and joined the Democratic establishment in preferring a more sophisticated policy.

Republican Richard Nixon, who learned sophistication from establishment guru Henry Kissinger, will be remembered as the first U.S. president to lose a war. Nixon, on the establishment’s behalf and to the American people’s disbelief, also signed the treaty that forbade the U.S. government from defending America against ballistic missiles. Then, when China, frightened by Soviet military superiority, begged for America’s help, Nixon did not demand a price. Instead, he paid for the privilege of helping Beijing by downgrading America’s relations with the nationalist Chinese and throwing them out of the United Nations. Gerald Ford’s foreign policy, under the same Kissinger, was to facilitate the Soviet Union’s control over its empire. Ford let it slip out in a presidential debate by stating that the people of Poland were really free, although occupied by the Red Army. That slip elected Jimmy Carter, who proved far tougher toward the communist world. Carter, not any Republican, moved America away from Mutual Assured Destruction by retargeting U.S. missiles from Soviet cities to Soviet missile forces, and started the construction of new U.S. missile systems for precisely that purpose.

Propping Up the Soviet Union

Reagan had done his best to end the Soviet Union. But as it was coming apart, Republican Establishmentarians George H. W. Bush and his secretaries of State George P. Shultz and James Baker did their best to keep it together, aided by future Republican establishmentarian Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice. For once, their incompetence paid off.

In hot pursuit of “a new world order,” Bush “41” reacted to Saddam Hussein’s 1990 invasion of Kuwait by sending half million superbly equipped U.S. troops. But, by using them to do Saddam only a little harm, and then stationing some in Saudi Arabia, he earned a reputation for impotence for America, while inflaming the Muslim world’s paranoia about interference in their civilization. He then confirmed his combination of impotence and interference by undertaking “nation-building” in Somalia.

For its final defining act, the “Bush 41” administration set in motion (in 1994 the W.J. Clinton administration consummated) a deal by which the United States committed (with intentionally ambiguous fine print) to uphold the independence and territorial integrity of Ukraine in exchange for Ukraine giving Russia its huge stock of nuclear weapons. In 2014, as Russia annexed Crimea and threatened the rest of Ukraine, the U.S. government reneged with bluster rather than redeem a nutty commitment.

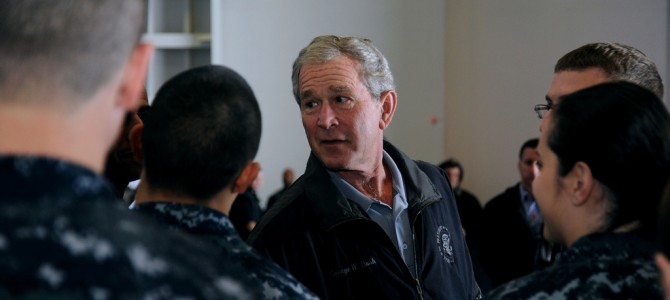

The George W. Bush administration finished off what remained of America’s stock of respect among nations. In the aftermath of 9/11, the Middle East’s potentates had quashed celebrations in their cities, terrified that American would take out rage on them for having stoked terrorism. President Bush’s September 20 speech, promising to make no distinction between terrorists and whoever helps them, reduced them to begging us for mercy. But Bush’s actions let them know that anti-Americanism is safer than ever.

Bush attacked Afghanistan’s Taliban—persons marginal to the Middle East’s anti-American terrorism—and settled down to the “nation building” that he had denounced as a candidate. Then he squandered the fear of America his overthrow of Hussein had sparked within other terrorist sponsors by agreeing to Saudi requests to occupy Iraq to settle its internal quarrels (i.e. to save the Sunni rulers from the Shia’s revenge). As American troops lost life and limb driving through perpetually re-filled minefields; as the Syrian regime acted as headquarters for the Muslim world’s war against the U.S. occupation (with private Saudi financing); as successive U.S. secretaries of State nevertheless continued to support Syria’s suzerainty over Lebanon in partnership with Iran; as Iran continued to kill Americans in Iraq while the Bush administration complained about it without retaliating: while George W. Bush extolled Islam as “the religion of peace” while Muslim terrorism continued to increase; and as “homeland security” impinged on Americans in increasingly partisan ways, the American people came to the conclusion that the Republicans really did not know what they were doing. Not unreasonable.

Reaping the Whirlwind

But the logic of partisanship had turned establishment Republicans into establishment foreign policy’s blindest defenders. They were sure that “the surge”—a program that consisted primarily of ceasing to fight Iraq’s Sunnis for control of Sunni-majority areas and instead of arming and paying them to control these areas—had “worked.” To do what, they were less sure. Republican establishment candidate John McCain said that U.S. troops should stay in Iraq for 100 years, if necessary.

As terrorists rampage over the world, as Russia and China show contempt for America, the American people reasonably desire a president who exhibits some sense of how America is to be defended. But Republican establishmentarians who promise to increase the defense budget and say that, in defense of America’s interest, “everything is on the table” will not be taken seriously.

Just what do they propose to do about what? With what? And what reason does anyone have to believe that any of these things will achieve what the American people want? Establishment Republicans should get used to such questions.