On Monday, the United States will experience the totality, a full solar eclipse that will move from Mexico into Texas before crossing 14 states and exiting into Canada. Though we previously had a total eclipse in 2017, we will not get another until 2045, and people are rightly excited. In response to this excitement, multiple locations in the country have naturally declared a state of emergency.

It isn’t that we’ve resurrected ancient beliefs about the eclipse. We’re not concerned that the gods are angry at the king, though perhaps we should be, or that the moon blocking the sun is a sign of impending doom. Rather, the states of emergency are out of concern that travelers to the states experiencing the totality might strain emergency services, so local governments are making sure to get their hands ready to scoop up some federal funds should the opportunity arise.

The states of emergency are silly, but the impetus for them is a cause for hope. In 2024, during a time in which our lives have been consumed by the digital realm, thousands and thousands of people will take time from their lives to look up from their screens and enjoy the manifest beauty of God’s creation. That they’ll promptly return to their screens to take awful amateur photos of the eclipse and then post them on social media is less heartening.

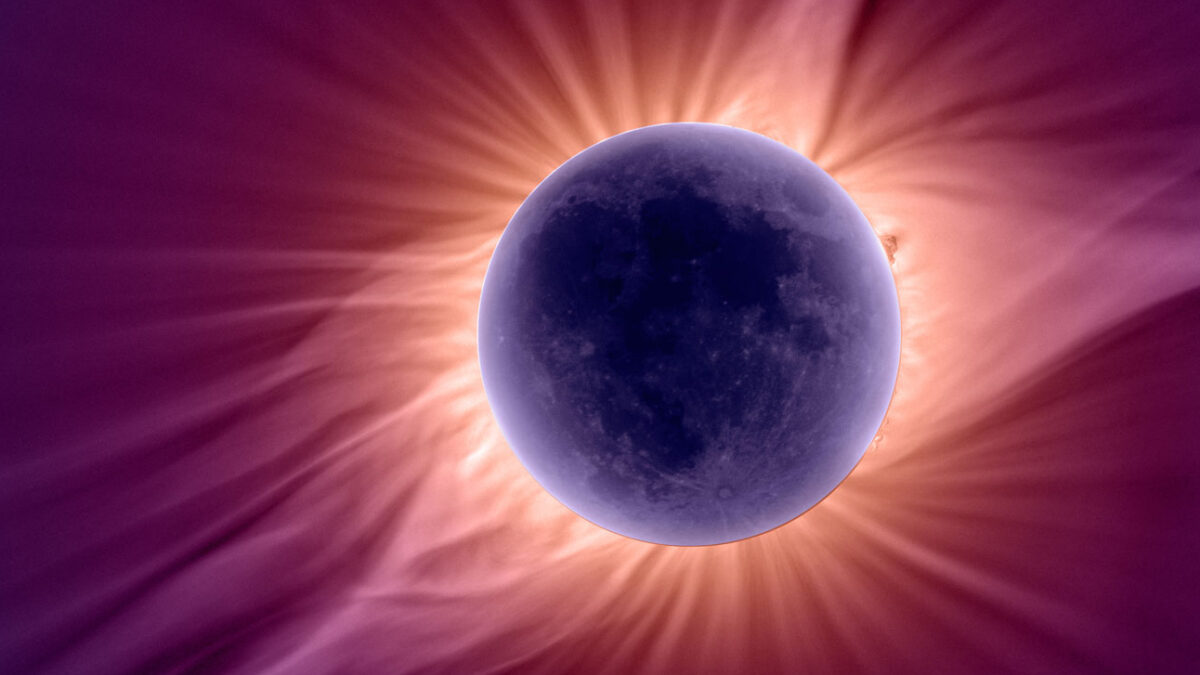

I know the lure. As a resident of a state experiencing the full eclipse, the odds that I’ll skip taking a photo are low, but I will at least feel bad about it, especially when I could just wait a few hours and download a much better photo, such as this one from 2017, and post that instead.

Solar eclipses have long intrigued man. Early myths suggested an eclipse was actually the wolf Skoll pursuing sun goddess Sol across the sky in an attempt to swallow her or that a dragon was swallowing the sun. Less grim was the belief that the sun and the moon were having more babies. Today, people worry more about the effects on pregnant women and household pets, which somehow make less sense than the ancient superstitions.

They don’t only produce worry, though. Total eclipses also produce awe. Writing in 1869, Maria Mitchell, the first female astronomer, described what she witnessed during that year’s totality.

Light clouds had for some time seemed to drift toward the sun; the Mississippi assumed a leaden hue; a sickly green spread over the landscape; Venus shone brightly on one side of the sun, Mercury on the other; Arcturus was gleaming overhead, Saturn was rising in the east; the neighboring cattle began to low; the birds uttered a painful cry; fireflies twinkled in the foliage, and when the last ray of light was extinguished, a wave of sound came up from the villages below, the mingling of the subdued voices of the multitude.

Instantly the corona burst forth, a glory indeed! It encircled the sun with a soft light, and it sent off streamers for millions of miles into space!

More recently, writer Annie Dillard waxed poetic on the total eclipse of 1979, saying:

The sky’s blue was deepening, but there was no darkness. The sun was a wide crescent, like a segment of tangerine. The wind freshened and blew steadily over the hill. The eastern hill across the highway grew dusky and sharp. The towns and orchards in the valley to the south were dissolving into the blue light. Only the thin band of river held a spot of sun.

Now the sky to the west deepened to indigo, a color never seen. A dark sky usually loses color. This was saturated, deep indigo, up in the air.

Trust me, your phone is not going to adequately capture the wonder and beauty described by Mitchell and Dillard. If you live in the path — or are one of the travelers heading to a state of emergency — you can witness it and live it in the moment. You can take time away from the chaos of daily life and look toward the heavens with your brothers and sisters, absorbing the majesty of it all, if only briefly.

For the totality will only last 3.5 to 4 minutes. During that time, the temperature will drop. Birds will flock and barnyard animals will start to bed down, thinking it’s dusk. Crickets and cicadas, should they emerge before then, will sing. It will be a brief window, but it will be an opportunity for us to let our inspiration flow, as it did for Mitchell and Dillard, and enjoy a spectacular heavenly event, one that doesn’t happen all too often.

Just as earlier generations ascribed mystic importance, we know, deep in our souls, that such celestial occurrences remind us of the majesty of the cosmos, of the intricacies of life, and of the fact that man is not the master of the universe. That it is happening in the Easter season only serves to highlight the fact that we are God’s creation, living in His glorious design, blessed by His fruits, and looking toward the heavens. For as C.S. Lewis wrote in Mere Christianity, “If I find in myself a desire which no experience in this world can satisfy, the most probable explanation is that I was made for another world.”

The eclipse may be visible from this world, however briefly, but it is not of it. Enjoy the rare opportunity to bask in its glory and be reminded that we too were made for another world.

For more on space, science, and the totality, check out this episode of “Cookin’ Up a Story,” a podcast I produce and co-host with Joe Wilson, founder of the World Championship Squirrel Cook Off, in which we talk with a Ph.D. student in space science from the University of Arkansas.