The odds you’ve seen this year’s ”Best Picture” winner are probably about as low as the odds you’ll tune into the Oscars or the odds you’re a fan of all three hosts. What about your odds of playing today’s Wordle?

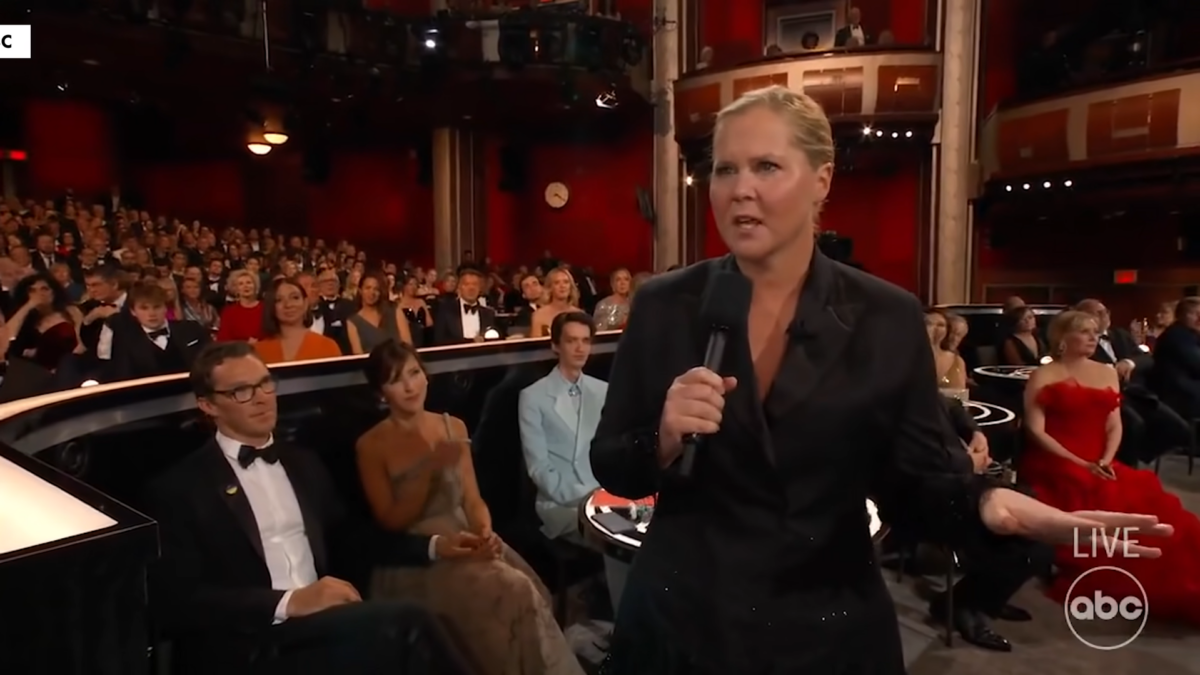

It’s possible a hit like ”Don’t Look Up” wins the ceremony’s top prize, but given the Academy’s recent track record, it’s more likely a less-popular film will take home the statue. That’s at least partially why Americans are much less likely to tune in when Regina Hall, Amy Schumer, and Wanda Sykes host the broadcast next month.

There are many explanations for the Oscars’ steady ratings decline: a dearth of nominated blockbusters, politics, length. But the most influential factor would seem to be choice.

The ceremony was first broadcast in 1953 on NBC. Bob Hope hosted. Thirty-four million tuned in. As recently as 2014, the Oscars were drawing audiences comparable with broadcasts in the 1980s. The most-watched ceremony of all-time remains 1998’s affair, when 58 million viewers watched “Titanic” win the night. Only nine million people watched last year, continuing the ceremony’s steep and dramatic decline.

But choice alone can’t explain this pattern. It’s true the vast proliferation of entertainment options is steering us all into niches, eliminating water-cooler fodder and shared cultural experiences. Yet Sunday’s Super Bowl broadcast drew 112 million viewers. The most-watched Super Bowl ever aired in 2015, long after the Oscars’ peak.

Americans still watch movies, so why are the Academy Awards (and other award ceremonies) suffering while the Super Bowl flourishes? As we covered three years ago, popular culture is dying. The consequence is a decline in shared values and cultural touchstones. There will be fewer Jennifer Anistons and more Sydney Sweeneys, fewer “Titanics” and more “Parasites,” fewer Cronkites and more Acostas. There’s good and bad in all of this, as gatekeepers lose power and better products win out.

Enter Wordle. The New York Times’ traffic jumped significantly after acquiring the game, which is skyrocketing in popularity. Morning Consult’s figures from a month ago had 14 percent of Americans playing it. That’s in the same ballpark as the portion of the country that had even heard about several of last year’s ”Best Picture” nominees.

Part of Wordle’s appeal is the shared experience. Everyone is guessing the same word. When people post and send their results, the point is that we see our different paths to one common destination. We all play exactly once a day with exactly the same result. The game would be less fun if people played for different words at different rates. There’s something magnetic about shared entertainment experiences.

But it requires the will and the knowledge to create something people want to consume. The Academy is lost on both counts, culturally insulated more every year thanks to the ”Coming Apart” phenomenon, which also begot a snobbishness that made the awards less relevant. A similar fate has befallen legacy media like The New York Times, which at least had the business acumen to acquire Wordle after seeing its success.

Could any given late-night host put up numbers that compete with Johnny Carson? I don’t think so, even if someone managed to channel Carson’s wide appeal. The format worked in the golden age of mass media, but 24/7 news, YouTube, streaming, and other factors have made the ritual of tuning in live on a nightly basis outmoded. This is where the Academy’s selection of Hall, Schumer, and Skyes comes in.

Stephen Colbert is both the most polarizing and most successful late-night host of the networks. Why? He corners a niche. His writers don’t sit around at noon and think, “How can we make America laugh tonight?” They think, “How can we make liberal Boomers laugh tonight?” If the Academy can turn the Oscars into must-see TV for progressive millennials, maybe the only slice of the population that enjoys Amy Schumer, they could get more bang for their buck. (More here and here.)

It’s probably more likely they’re just so clueless as to think what America wants right now is MORE AMY SCHUMER. But it’s worth following the proliferation of the Colbert Model because it’s the only way struggling institutions will be able to limp ahead. The New York Times pulled a perfectly reasonable op-ed from Sen. Tom Cotton, R-Ark., back in 2020 because the paper is no longer responsive to a broad audience, but to a much narrower one.

These silos bring with them blind spots that are hard to correct and exacerbate cultural resentments. If reports were correct that Dr. Dre felt censored at the Super Bowl, he should consider that his paycheck and reach would be a whole lot lower if the show’s producers weren’t zealously guarding the event’s wide appeal.