Self-censoring is an essential survival skill under an authoritarian regime. Understandably, the majority of the Chinese people has long been conditioned to not openly discuss or write about certain topics that are “sensitive” to the image and pride of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), such as the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976) and the three Ts: Taiwan, Tibet, and the 1989 Tiananmen Square Massacre.

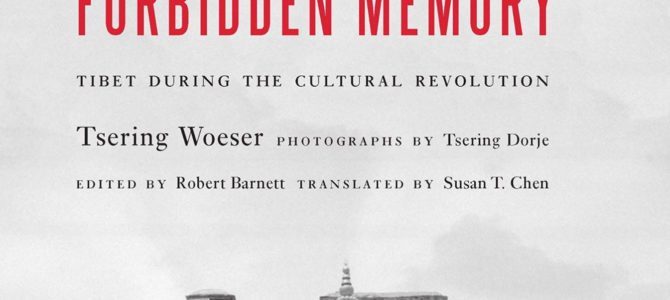

The CCP has made sure that anyone who dares to talk about any of these subjects openly is severely punished, unless they repeat only the CCP talking points. Therefore, it is extremely rare to read a book that covers not one, but two coinciding “sensitive” topics – Tibet during the Cultural Revolution – by a Tibetan author, Tsering Woeser, who still lives in China. The title of the book, Forbidden Memory: Tibet during the Cultural Revolution, couldn’t be more fitting.

The CCP version of Tibetan history has three main talking points. First, Tibet has always been part of China since the beginning of time; second, Tibetans lived a miserable life until the People’s Liberation Army “liberated” Tibet in 1950; and third, the CCP has tremendously improved the lives of Tibetans since 1950. The real history of Tibet contradicts these talking points.

The Betrayal of Tibet

While ancient Chinese emperors interacted with Tibet’s rulers and religious leaders in many different ways, including marrying Chinese princesses to rulers of Tibet, Tibet managed most affairs on its own. In 1913, Tibet declared its independence from China. In 1931, in an attempt to build a broad base of political support, the CCP declared that Tibetans and other peoples in China were entitled to full independence. It quietly changed its position when it became clear the CCP was winning the Civil War against the Nationalists and was about to rule China.

The CCP’s then leader, Mao Zedong, sent the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) to Tibet in 1950. Without a strong army or international backing, the Tibetan government, led by the fourteenth Dalai Lama, surrendered to the PLA in May 1951. Initially, the CCP promised to preserve Tibetans’ social, economic, and political structures, as well as respect Tibetans’ cultural traditions and religious practices. Hence, the Dalai Lama was left in charge, albeit with Beijing’s supervision.

However, the CCP immediately launched radical socialist reforms in provinces neighboring Tibet, where other ethnic minorities and some Tibetans resided. Monasteries were destroyed, properties confiscated, and landowners and religious leaders persecuted. Thousands of refugees from these regions escaped to Lhasa, the capital of Tibet.

The city staged an armed uprising against Communist China’s rule in March 1959 but was quickly overpowered by the PLA. The Dalai Lama fled to India. About 80,000 Tibetans followed him until the PLA sealed the Sino-India border.

The uprising provided the CCP a pretext to break its promise to the Tibetans. The CCP quickly imposed on Tibet the same radical socialist reforms that had swept China since 1949. The obliteration of Tibet’s society and culture caused by these policies reached its height during the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976).

Since then, the CCP has largely been successful in suppressing all discussion regarding Tibet during the Cultural Revolution. In China, history books, literature, films, or even statistics about Tibet’s modern history only date back to 1979, as if Tibet’s history before that date ceases to exist. Interestingly, it took a Tibetan who was also a member of the CCP to document what truly happened in Tibet during the Cultural Revolution, through his camera lens.

His name is Tsering Dorje. When the PLA marched into Tibet in 1950, swept by the revolutionary fervor and the promise of a good life, Dorje joined the PLA at age 13. He later became a mid-level PLA officer. His hobby was photography. Because of his rank, he was able to roam freely in Tibet to take photos.

None of these photos were published until his daughter, Tsering Woeser, discovered them after Dorje passed away. Recognizing the historical value of these photos, Woeser spent several years organizing them into a book, adding illustrations, interviewing some of the subjects in the photos, and providing historical context. Her project became this book, Forbidden Memory.

To intimidate Woeser into giving up this book project, the CCP pressured her employer to fire her and banned all her works from being published in China. Forbidden Memory was eventually published in Taiwan in 2006, and now, there is an English translation.

Struggle Sessions and the Sacking of Monastaries

This book consists of 11 galleries of photographs taken by Tsering Dorje in Tibet between approximately 1964 and 1976. Among the hundreds of images in this book, I want to highlight two series of photos that left a great impression on me.

The first series was about the sacking of Jokhang. Jokhang is one of the most famous monasteries built in the mid-seventh century. It housed precious Buddha statues and sacred artifacts. Traditionally, during the Tibetan New Year, tens of thousands of monks from the major monasteries in Lhasa would gather at the Jokhang for the annual festival known as Monlam Chenmo, meaning “Great Prayer.” Ordinary Tibetans would wait in long lines to get into Jokhang to make offerings and ask for blessings. It’s fair to say that the history of Jokhang is also in large part the history of Tibet.

Jokhang was sacked on August 24, 1966 by Tibetan Red Guards, made up by militant students from both Lhasa High School and the Tibetan Teachers’ college, under the leadership of Tibetan students who took a break from studying at prestigious colleges in Beijing. Many of them came from well-off Tibetan families.

One photo shows that broken statues, ritual items, and debris filled the center of Jokhang’s Great Courtyard. Some very young-looking Red Guards were in the middle of throwing more items down from Jokhang’s upper level. Another photo shows sacred religious texts and prayer wheels were burned. Most of the Buddha’s statues were toppled. The statues that were made of clay were dumped into the Lhasa River. The metal ones were melted to make industrial parts.

Only one Buddha statue remained at Jokhang because of his size, but he was stripped bare of his robes and ornaments: “gold paint on the statue’s face and body were scraped off, and the precious stone inlaid between his eyebrows were looted, along with the antique gold earrings that he wore and the golden lamps and bowls in front of him.” Later, a PLA garrison turned the second floor of Jokhang into its office and dorms for soldiers, while raising and slaughtering pigs in the courtyard.

Jokhang was one of many monasteries that were destroyed during the Cultural Revolution. According to the Chinese government’s own account, there were 2,700 monasteries in Tibet in 1959. By 1976, only eight remained.

Another series of photos depicted the struggle session with Dorje Phagmo, the most famous female reincarnated lama in Tibet. She followed the Dalai Lama to India in 1959 but returned because the CCP announced to the world that it would welcome any escaped Tibetan back to Tibet, promising “no killing, no imprisonment, no trial, and no struggle session” against them.

When Phagmo returned, she was hailed as a “patriot.” She was a guest of honor in Beijing for the celebration of the 10th anniversary of the founding of Communist China and was received by Chairman Mao. But after the CCP was done with using her for photo ops to boost its images, punishment followed.

Two months after giving birth to her son, she was forced to wear a ceremonial robe and hold a heavy ancient vase, with piles of heavy textiles loaded on her back, which compelled her to bow down, in the middle of the courtyard in her own house, with her parents standing next to her. The three were surrounded by hundreds of angry mobs whose fists were high in the air while shouting insults and revolutionary slogans. One of the fists looked awfully close to Dorje’s face. It isn’t clear if she was hit by it.

This book has many similar pictures like this: Tibetans who used to be revered and respected now being humiliated in public struggle sessions, and the mobs included their neighbors, household staff, even monks and nuns. With images like these, no wonder the CCP banned Forbidden Memory in China. This book presents indisputable visual evidence that contradicts the CCP’s talking points about Tibet.

Destruction From Within

It is easy to conclude from this book that the CCP should be condemned for destroying Tibet’s cultural heritage and ruining the lives of Tibetans, and that no one should trust the CCP to keep its promises. While both of those conclusions are true, we should also ask an uncomfortable question: Would the CCP’s policies have caused as much damage, had many Tibetans not taken a part in it?

Some Tibetans participated in the demolition of their homeland out of fear. One interviewee told Woeser that not participating in these activities wasn’t an option, because that might cause people to lose their food ration or even become targets of the next struggle session.

However, many Tibetans supported the CCP’s policies with enthusiasm. It seems they sincerely believed that socialism was their new religion and that Chairman Mao was their new deity. Based on her interviews with Tibetans, Woeser concludes, “Events that took place between 1950 and 1959 seem to have shown that the new god was so powerful that the ancient gods of the land had been defeated. When the Cultural Revolution took place, the new god took over.”

This explains why in photos after photos, so many Tibetans actively destroyed their monasteries, eagerly raised their fists high in the air, and loudly condemned figures they used to reverent with almost religious fervor.

British historian Luke Kemp once said, “Great civilizations are not murdered. Instead, they take their own lives.” What he meant was that external force only bears partial blame for the destruction of a civilization. The harm done by its own people is the most lethal. It’s a lesson reinforced by this book and a lesson we should remember as we ponder the future of the United States.