One person in the middle of the present pandemic you won’t hear whining about quarantine fatigue or supermarket lines is the Rev. Hugh Vincent Dyer, because he’s too busy trying to help the elderly, at-risk New Yorkers he serves by bringing them spiritual comfort, along with a bit of culture.

Father Dyer is a Catholic priest and member of the Order of Preachers, popularly known as the Dominicans. You may have read about him recently in The New York Times, discussing his decision in the wake of coronavirus to move out of the friary he shared on the Upper East Side with other members of his order. Dyer took the unusual step of taking up residence at the nursing home in the area where he has served as chaplain since December 2019.

There are about 360 elderly residents at the nursing home, not all of them Catholic. In addition to broadcasting Mass, the rosary, and meditations from the facility’s chapel via CCTV, Dyer makes himself available to anyone who wants his counsel or company. As in many parts of the country, strict social distancing measures have been in place for many weeks now, given the high rate of susceptibility among the elderly.

This means the chapel is mostly empty of visitors these days, apart from a few of the nuns who work at the home. However, with the ability to reach all the isolated residents at once through CCTV, Dyer has become more creative in connecting with his flock.

Poetry Brings Back Memories for Residents

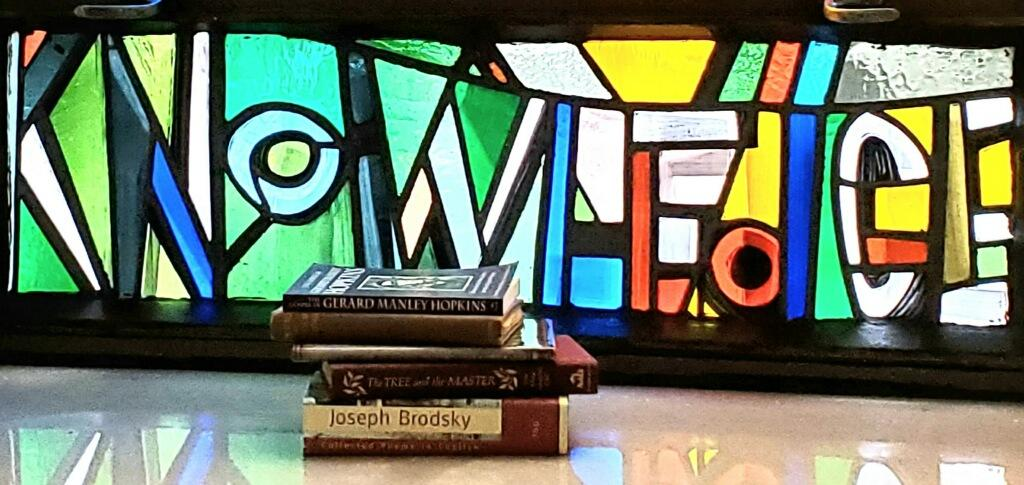

Every Tuesday and Thursday, Dyer uses the internal television system to broadcast what he calls a “Cultural Miscellany,” in which he looks at a variety of topics and tries to link them with poetry and the arts. He recently gave a talk on trees, for example, and their relationship to both culture and scripture, using “A Ballad of Trees and the Master” by Sidney Lanier (1842-1881) as a jumping-off point. On another occasion, his reading of “The Builders” by Sara Henderson Hay (1906-1987), a retelling of “The Three Little Pigs,” led to a reflection on the material aspects of practicing the virtues.

The effort was partly inspired by a conversation Dyer had with one of the elderly residents, who as a young man had studied poetry under W.H. Auden (1907-1973) at Columbia University, and who shared his recollections of Auden as both poet and professor. “With poetry,” Dyer realized, “you can do a lot to jog the residents’ memories.”

The effort was partly inspired by a conversation Dyer had with one of the elderly residents, who as a young man had studied poetry under W.H. Auden (1907-1973) at Columbia University, and who shared his recollections of Auden as both poet and professor. “With poetry,” Dyer realized, “you can do a lot to jog the residents’ memories.”

A few weeks ago, he read “Paul Revere’s Ride” by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (1807-1882), and a resident later told him she had been very touched by his selection. She still remembered almost all the lines from when she had memorized them as a girl, and she was pleased to be able to recite the poem in sync with his broadcast.

One poem Dyer shared during his program that proved to be particularly popular with the residents was “The Plain Facts” by British poet Ruth Pitter (1897-1992), which talks about the joy of living, making friends, and smiling. “People took to this poem just before Covid really hit,” notes Dyer. “I told them that it’s important to remember to pray for other people whenever we find ourselves in difficulties, but also to try to smile.” After he read the poem, the residents rather impishly began to chide him if he didn’t have a smile on his face when he dropped by their rooms during his daily rounds.

Sometimes the residents send requests to have the chaplain recite and reflect on some of their favorite poems. He shared “Simon the Cyrenian Speaks” by Harlem Renaissance poet Countee Cullen (1903-1946) after one of the residents, a retired teacher from Harlem, asked him to read it on his program. He did so alongside two other biblically inspired poems: “The Donkey” by British author G.K. Chesterton (1874-1936) and “What The Fig Tree Said” by American poet Denise Levertov (1923-1997).

“For some of the residents, these are new poets or new poems,” notes Dyer, “and I’m trying to connect things like poetry and culture and spirituality without making it stale for them. We’re all living with a new reality together, here in the nursing home.”

The residents enjoyed another Levertov poem, “Servant Girl at Emmaus,” at Easter. That poem was inspired by the painting of the same title by Diego Velázquez (1599-1660). This allowed Dyer both to read the poem and to talk about the painting, since the residents enjoy when he describes a picture to them.

“Residents tell me that they like to hear descriptions of things, because it allows them to remember more from their own memories.” He notes how on one occasion, his description of bread caused a resident to remember vividly the texture and aroma of the homemade breads her mother used to bake.

The Residents Love ‘the Evening Movie Guy’

After realizing he could use the CCTV system to show movies in-house, Dyer also began screening films. Sometimes he appears on camera before the screening to give a brief introduction, but at the very least, he always uses the public address system within the nursing home to announce the film he will be starting shortly.

“I’ve become ‘the evening movie guy,’” he jokes, noting the reaction has been so positive that he’s added afternoon matinees on the weekends. Selections have run the gamut from old classics to performance films to documentaries.

So far, several of the films the chaplain has selected have received repeat showings, thanks to enthusiastic responses from the residents. They loved the classic Bing Crosby film, “Going My Way” (1944), a concert by the late jazz pianist and composer Mary Lou Williams, a biopic on the 19th-century French saint Thérèse of Lisieux, and a performance of “Swan Lake” by the Kirov Ballet.

So far, several of the films the chaplain has selected have received repeat showings, thanks to enthusiastic responses from the residents. They loved the classic Bing Crosby film, “Going My Way” (1944), a concert by the late jazz pianist and composer Mary Lou Williams, a biopic on the 19th-century French saint Thérèse of Lisieux, and a performance of “Swan Lake” by the Kirov Ballet.

Another repeat request was for the somewhat lesser-known Bette Davis film “The Catered Affair” (1956), a morality tale about a dowdy Bronx housewife, her cab driver husband, and their newly engaged daughter, who come into conflict over whether to throw an elaborate wedding. Before the screening, Dyer reminded the residents to pray for New York cab drivers, who were already suffering from loss of income before the pandemic hit.

Dyer’s Flock Can Still Appreciate Culture

Like his poetry readings and descriptions of art, sometimes Dyer’s film choices can trigger forgotten memories and fascinating stories. For example, after a screening of the musical “Show Boat” (1936) one evening, a resident recalled to Dyer that she had been a camp counselor one summer when the film’s star Paul Robeson came to sing for the campers. Another resident, a cloistered nun who was temporarily recuperating at the residence, told him she hadn’t seen a film in decades, so many of the movies were a walk down memory lane of her youth before entering the convent.

Dyer recognized early in his assignment that his flock of elderly New Yorkers quarantined under a pandemic was a special one, but he characteristically downplays his role in finding a unique way to reach out to them in very difficult times.

“For me, it was just an acknowledgement that our elderly have lived in this city for many years,” he explains. “And even though the museums and other cultural institutions are currently closed or no longer accessible to them, they can still have access to culture.”

Despite, or perhaps because of, their vulnerability and greater degree of isolation, the home’s residents seem to be sticking to Ruth Pitter’s poetic exhortation to keep smiling. Of course, with many of them being native New Yorkers, they may be more accustomed to perceiving humor in the ironies and trials of life — even in trials as great as the present one. As one resident commented to Dyer after Mass recently, “Look, Father, I’m still smiling!”