Let us pause in life’s pleasures and count its many tears,

While we all sup sorrow with the poor;

There’s a song that will linger forever in our ears;

Oh! Hard times come again no more.

Written 166 years ago, this melodic folk lament seems to perfectly capture the pathos of the present day, especially as the last verse ends at a graveside:

Tis a sigh that is wafted across the troubled wave,

‘Tis a wail that is heard upon the shore

‘Tis a dirge that is murmured around the lowly grave

Oh! Hard times come again no more.

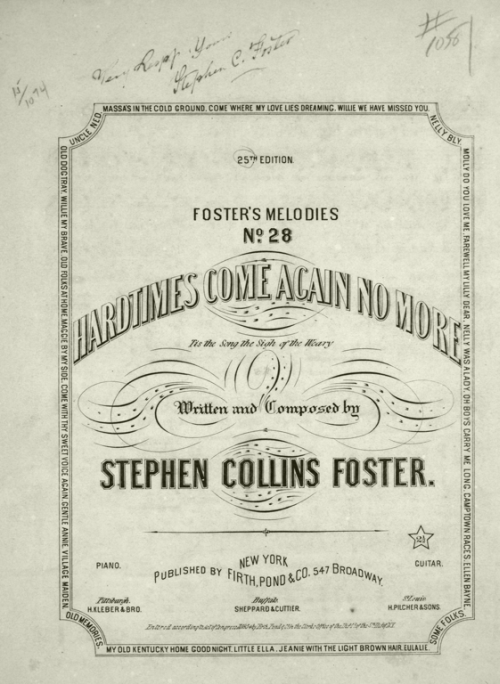

Those who grew up singing the nonsensical yet delightful “O Susanna” or chortled through the “doo-dahs” of “Camptown Races” may be surprised to learn that this ballad, “Hard Times Come Again No More,” was written by the same composer: Stephen C. Foster (July 4, 1826-January 13, 1864) one of America’s earliest and most prolific songwriters. His is a complicated history of a complicated time.

Foster wrote nearly 300 compositions, beginning with the enormously successful “O Susanna,” published when he was just 21, and ending with the lyrical “Beautiful Dreamer,” published March 4, 1864, two months after he died at the age of 37.

“The songs of Stephen Foster…have been a source of inspiration to every writer of popular songs. I think if you were to ask any of the boys in Tin Pan Alley which song he would rather have written than any one of his own, he would pick one of Foster’s,” said the famous American composer Irving Berlin.

Within two months of his death, Harper’s New Monthly Magazine proclaimed, “The air is full of his melodies. They are our national music.” Kentucky and Florida chose Foster songs for their state songs, “Old Kentucky Home” and “Old Folks at Home,” respectively, even though Foster traveled South only one time, on a steamboat down the Mississippi to New Orleans in 1852. His songs resonate with people of many cultures, and have been found in the mountains of Tibet, black South Africa and Japan.

An 1854 Cholera Outbreak in Philadelphia

“Hard Times” reflected the troubles of Foster’s native Pittsburgh in 1854 when a cholera outbreak killed 400 people in two weeks and unemployment was at “unprecedented levels,” writes Ken Emerson, author of “Doo-dah!: Stephen Foster And The Rise Of American Popular Culture.” The song also could have reflected Charles Dickens’ serialized novel “Hard Times” about the Industrial Revolution. It crossed the ocean to Lancashire, England during the Cotton Famine in the 1860s when thousands were unemployed.

Foster knew his own hard times: His oldest sister, Charlotte Susanna, for whom his first big hit was named, died at 19 when he was just three years old. A year later, his baby brother James died. His family faced financial struggles and lost their home.

Foster dealt all his life with an unstable income from music. He and his wife, Jane Denny McDowell, who married on July 22, 1850, separated more than once. And his lifelong friend and one-time collaborator, poet Charles Shiras, died of consumption in 1854 at the age of 29. Both Foster’s parents died the following year.

Foster was born outside Pittsburgh on July 4, 1826, one of the youngest of nine children to a politically prominent Democratic family. His father William Barclay Foster, a merchant, served three terms in the Pennsylvania legislature and was twice mayor of Allegheny City (now part of Pittsburgh).

Foster was taught at private academies and studied music with German-born Henry Kleber, an accomplished musician and music dealer. Foster’s love for music was obvious at a young age. He wrote his first song at 14 and taught himself to play the clarinet, flute, piano, and guitar.

But working in the family business was required. At 20, he went to work as a bookkeeper at his brother’s steamboat company in Cincinnati. A year later, in 1848, he wrote “Oh Susanna.” Its rousing success launched his songwriting career: previously, no American song had sold more than 5,000 copies. “Oh, Susanna” sold more than 100,000 copies the first year.

It became the rallying cry of the ‘49 gold rush. Laura Ingalls Wilder printed a Gold Rush verse in her book, “Little House on the Prairie.”

I come from Salem city with my washpan on my knee

I’m going to California, the gold dust for to see

I shall soon be in Frisco, and there I’ll look around

And when I see the gold lumps, I’ll pick them off the ground.

How the Ballad Rolled Around America

The tender ballad “Hard Times” was first recorded by the Edison Male Quartette on a wax cylinder in 1905. It was “rediscovered’ in the 1980s and recorded by artists as diverse as rock star Bruce Springsteen and British opera singer Jonathan Gunthorpe.

It was recorded in 1992 by country artist Emmylou Harris and sung in concerts over the years by folk singer Bob Dylan. The 2000 “Appalachian Journey” offers an instrumental and vocal arrangement featuring James Taylor and Yo-Yo Ma. Documentary writer Ken Burns used gospel singer Mavis Staples’ soulful rendition of the song to open the second episode of his documentary miniseries, “Country Music.”

Foster is called the first professional songwriter, but he was “a pioneering professional in a profession that didn’t exist yet,” wrote Deane Root, a former curator for the Stephen Foster Memorial. “The Foster Hall Collection has editions of ‘O Susanna’ by 28 different publishers during Foster’s lifetime, but only one was authorized and one paid him”: $100.

Not Everything Foster Did Deserves Admiration

Foster’s music is not without controversy. Early in his career, Foster wrote for the then-popular and now anathema blackface minstrelsy, where white singers blacken their faces and sing in derogatory dialect, acting like buffoons in a cruel parody of African Americans. It is now roundly condemned, as Gov. Ralph Northam of Virginia learned last year when a 1984 yearbook picture surfaced, showing him in either blackface or a Klu Klux Klan hood.

While just 26 of Foster’s nearly 300 compositions were written for minstrels, they are among his best known. “O Susanna” was a minstrel tune, and its original second verse would offend today. The words were changed over time, so that verse has not been sung in more than a century. In 1970, James Taylor recorded “O Susanna” on his hit album “Sweet Baby James.”

A bronze sculpture of the composer located near the Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Pittsburgh was removed two years ago. The sculpture, by Italian immigrant Giuseppe Moretti, featured a 10-foot tall Foster, seated with a notebook in hand, and an African-American man strumming a banjo.

Foster’s style of minstrel songs changed over time. Scholars have pointed out that his song, “Nelly Was a Lady,” published in 1849, was the “first-known song for the mass market to name an African-American woman a ‘lady’ and to portray a married African-American couple as a faithful, loving husband and wife destroyed by slavery.”

In a speech to the Rochester Ladies’ Anti-Slavery Society in 1855, the noted black abolitionist Frederick Douglass lauded Foster’s “Old Kentucky Home” and “Uncle Ned,” saying the tunes “can make the heart sad as well as merry, and can call forth a tear as well as a smile. They awaken the sympathies for the slave, in which anti-slavery principles take root and flourish.”

Democrats in the Days They Supported Slavery

Politically, Foster’s family were Democrats, no friend of abolitionists at that time. His sister Ann Eliza was married to Rev. Edward Buchanan, brother to President James Buchanan, a supporter of Southern causes and the last Democratic president before the Civil War.

But Foster was a lifelong friend of poet Charles Shiras, with whom he wrote a play. Shiras published an abolitionist newspaper in Pittsburgh called The Albatross. Foster’s father-in-law, Andrew Nathan McDowell, was a prominent physician in Pittsburgh who sponsored the first black medical student, Martin Delaney, to attend Harvard University and helped pay his tuition.

Clearly influenced by Harriet Beecher Stowe’s “Uncle Tom’s Cabin,” Foster wrote the compelling “Old Kentucky Home” in 1852, which he originally titled “Uncle Tom, Good Night.” His music was included in some of the earliest presentations of the play.

By the late 1850s, Foster was no longer writing minstrel music, focusing instead on parlor songs and other pieces, including the “Social Orchestra” a score with 83 pages of music and his lilting “I Dream of Jeannie with the Light Brown Hair,” written about his wife, Jean.

Foster’s Hard Times Return

By the 1860s, and the start of the Civil War, Foster was struggling with composing tunes that resonated with the public. Meanwhile, “Hard Times” became a soldier’s parody: “Hard Tack Come again no more.” Hard tack was a hard, tasteless “biscuit” made with flour, water, and salt shipped to soldiers from Union and Confederate storehouses.

Josiah Fowler of the First Iowa Infantry wrote in June 1861:

Let us close our game of poker, take our tin cups in our hand

As we all stand by the cook’s tent door

As dried mummies of hard crackers are handed to each man.

O, hard tack, come again no more!

Foster’s own hard times returned. He wrote prodigiously, completing more than 98 songs, but he couldn’t match the financial success or popularity of his earlier songs. He was living alone in a cheap Bowery hotel room, selling songs for cash, and drinking too much.

On January 10, 1864, weakened by a fever and an untreated burn on his leg, he collapsed in his room and struck his head on the wash basin. He died three days later at Bellevue Hospital. In his leather wallet was 38 cents and a scrap of paper that said, “Dear friends and gentle hearts.”

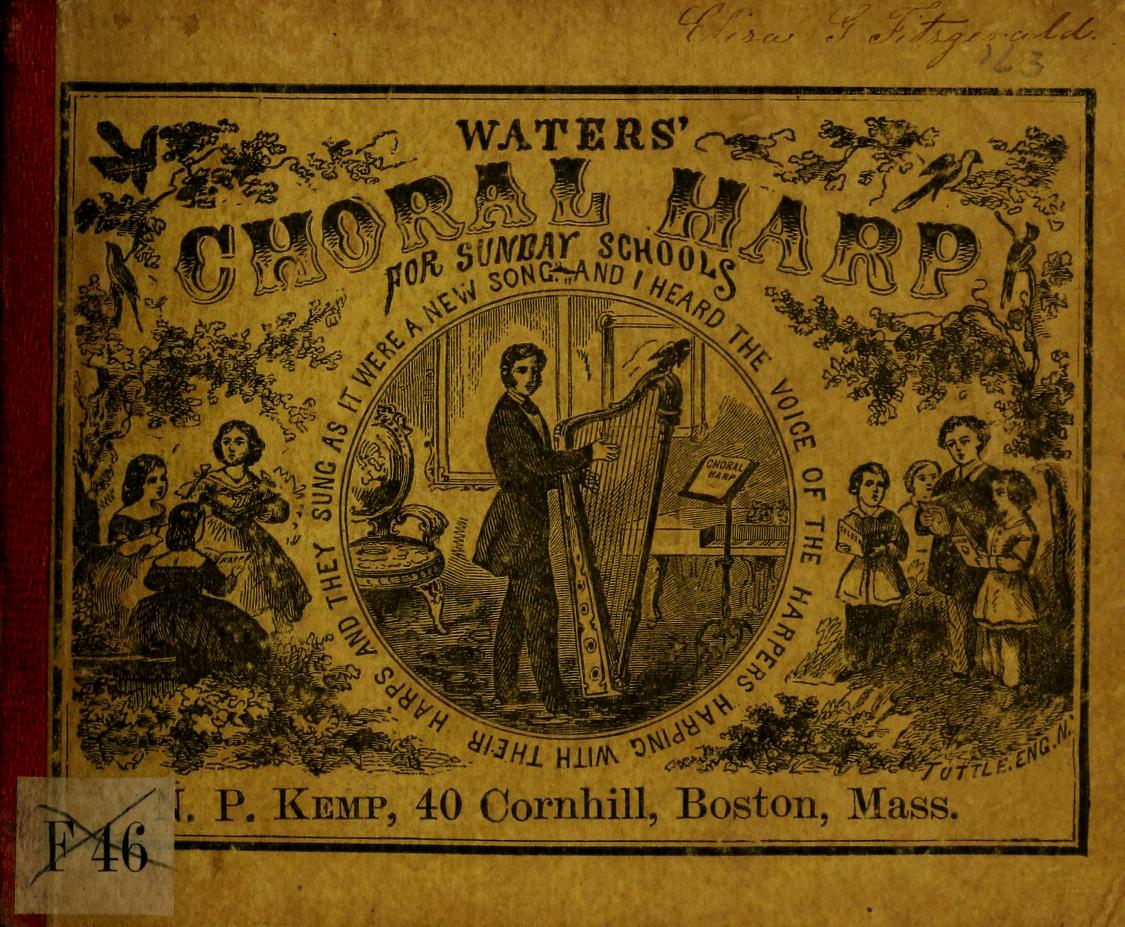

Among Foster’s last songs were Sunday School hymns published in Waters’ Choral Harp in 1863. While little known, they show the heart of a composer whose songs carried the melodies of angels.

When I hear the silvry notes of love

from the birds gaily singing in the tree,

Then I feel that God still reigns above,

And the angels are singing unto me.

Music from above

Strains of joy and love,

When my soul is filled with melody,

then the angels are singing unto me.