This November 9 marked the 30-year anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall, a notorious symbol of the oppression of communism and socialism. Yet people who love liberty cannot yet declare victory on this day of commemoration each year, because the battle hasn’t been won: socialism is staging a comeback in Western democracies, especially in the United States and United Kingdom.

It’s worth looking back at how the Berlin Wall was built. After World War II, Germany was a country divided. The regions occupied by the United Kingdom, United States, and France formed the Federal Republic of Germany, or West Germany, a free-market-oriented democracy. The areas occupied by the Soviet Union formed the German Democratic Republic, or East Germany, a Socialist regime.

This division extended into Berlin, creating West Berlin and East Berlin. Thus, one of the most dramatic and consequential social experiments in human history began: capitalism versus socialism, freedom versus tyranny, a free market economy versus central planning, command, and control.

Germans on both sides of the division spoke the same language and shared the same cultural heritage and ethnicity. Both sides, prior to their separation, had suffered similar destructions of infrastructure and severe damage in the economy.

Prior to Germany’s surrender in 1945, regions in East Germany retained a slightly higher gross domestic product per capita compared to West Germany. In other words, East Germany had a head start when the competition between capitalism versus socialism began, but as the chart (created by Daniel Mitchell, a libertarian economist) below illustrates, the two countries’ economies rapidly diverged.

B.R. Shenoy, a prominent economist in India, noticed the significant differences of the two economic models in the divided city of Berlin in as early as 1960. He observed that in West Berlin, “Rebuilding is virtually complete…The main thoroughfares of West Berlin are near jammed with prosperous looking automobile traffic, the German make of cars, big and small… The departmental stores in West Berlin are cramming with wearing apparel, other personal effects and a multiplicity of household equipment, temptingly displayed.”

In contrast, when Shenoy went to East Berlin, he saw “a good part of the destruction still remains; twisted iron, broken walls and heaped up rubble are common enough sights… Buses and trams dominate the thoroughfares in East Berlin; other automobiles, generally old and small cars, are in much smaller numbers than in West Berlin… The food shops in East Berlin exhibit cheap articles in indifferent wrappers or containers and the prices for comparable items, despite the poor quality, are noticeably higher than in West Berlin.”

Interestingly, if we leave the specification of location in this paragraph blank, what Sheony observed could have been replaced by any socialist countries mirroring the same scene, whether of China in the 1970s, or Venezuela in 2010. Socialism consistently produces similar devastating results, no matter where it has been attempted.

Shenoy wasn’t the only one who noticed the drastically distinct economic situations of East and West Germany in 1960. People in East Germany were aware of their poverty and political oppression, in contrast to the freedom and prosperity their families and friends enjoyed in West Germany since as early as the 1950s. East Germans wanted out.

Before 1961, people on both sides of Berlin could still travel freely back and forth, and only East Germany soldiers and border guards patrolled the dividing line of the city and set up checkpoints. Still, they didn’t try to stop people from going to the west side. About 60,000 East Berliners commuted to West Berlin every day to get to good-paying jobs. Consequently, an estimated 2.7 million people fled East Germany between 1949 to 1960.

Desperately trying to stop this large exodus, the socialist government in East Germany erected a 91-mile wall across the border of East and West Berlin after midnight on August 12, 1961. The Berlin Wall was enhanced multiple times in the next two decades with electric fences, watch towers, lighting systems, and even minefields to discourage people in the East from escaping. East German soldiers and border guards were also authorized from day one to shoot anyone who dared to scale the wall to reach the West. East Germany officially became a giant prison.

However, the Berlin Wall failed to deter many in the East from risking their lives for freedom and prosperity. About 5,000 people successfully made it to West Berlin in the next two decades. Unfortunately, close to 300 people died while trying. The area near the Berlin wall and the wall itself were referred to as a “death line.”

We all know what happened when President Ronald Reagan visited Berlin in 1987. What I didn’t know but later learned from the National Archives was that a career U.S. diplomat in Berlin at the time told President Reagan’s speech writer, Peter Robinson, that Reagan had to “watch himself: no chest-thumping, no Soviet-bashing and no inflammatory statements about the Berlin Wall.” The diplomat further asserted that “West Berliners, had long ago gotten used to the structure that encircled them.”

Robinson decided to do a little research. He asked several West Berliners on the street if they had gotten used to the wall. One man told Robinson: “My sister lives 20 miles in that direction, and I haven’t seen her in more than two decades. Do you think I can get used to that?” It turned out the American diplomat who warned Robinson couldn’t have been more wrong.

Based on his observations, Robinson wrote the speech for President Reagan, including the famous line, “Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall.” Of course, the State Department and National Security Council rejected the line and thought it was too provocative. Despite this, President Reagan ignored them, because he held much stronger conviction about the evils of socialism than his advisers did. On June 12, 1987, President Reagan delivered the following memorable lines:

Standing before the Brandenburg Gate, every man is a German, separated from his fellow men. Every man is a Berliner, forced to look upon a scar. . . . As long as this gate is closed, as long as this scar of a wall is permitted to stand, it is not the German question alone that remains open, but the question of freedom for all mankind. . . .

General Secretary Gorbachev, if you seek peace, if you seek prosperity for the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, if you seek liberalization, come here to this gate.

Mr. Gorbachev, open this gate!

Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall!

The speech was provocative, because it challenged the Soviet leader to do something morally compelling. By calling the Soviet Union out, President Reagan gave people who were held hostage by the failing socialist regime hope and encouraged them to fight for their freedom and a better life.

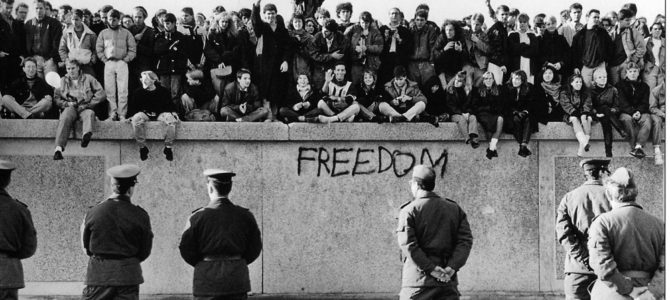

After the speech, East Germany witnessed many large protests. Two years later, on November 9, 1989, East Germany’s government finally announced that its people could now travel to the west freely. Soon, a large crowd of East Germans gathered at the Berlin Wall and chanted the words “We want out.” East German soldiers were overwhelmed by the size of the crowd, and opened the gate. People from both sides of the wall started to chisel away at the wall with any tools available. The Berlin Wall started to fall apart.

Robert Heilbroner, a left-leaning economist, wrote for The New Yorker in 1989, “The Soviet Union, China & Eastern Europe have given us the clearest possible proof that capitalism organizes the material affairs of humankind more satisfactorily than socialism.” He declares that “the contest between socialism and capitalism is over; capitalism has won.”

It would have been nice if we had buried socialism once and for all in 1989. Yet like a zombie, socialism refuses to die. It is staging an unfathomable comeback in West democracies, especially in the United Kingdom and United States. In the U.K., Jeremy Corbyn, a socialist who hijacked the Labour Party, is running to become the next prime minister. He promises a socialist revolution in the U.K. economy, aiming for the “redistribution of income, asset, ownership and power.”

In the United States, from the Green New Deal, to a hefty wealth tax and “Medicare for all,” the Democratic Party is now led by unapologetic socialists, some of whom are running to be the next president of the United States. They want to expand government control in every aspect of our lives, strip our freedom to choose, and radically redistribute our hard-earned wealth.

Even more troubling, according to the latest report by the Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation, 70 percent of millennials said they would vote for a socialist leader. Only 57 percent of millennials believe the Declaration of Independence better guarantees freedom and inequality than the Communist Manifesto does.

As we commemorate the 30-year anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall, we must realize that the contest between capitalism and socialism is far from over. Every one of us who cherishes our freedom and wants to preserve our republic needs to join the effort to speak up about the bloody history of communism and socialism, and help our youth debunk socialist fantasies and recognize the real dangers of such policies.