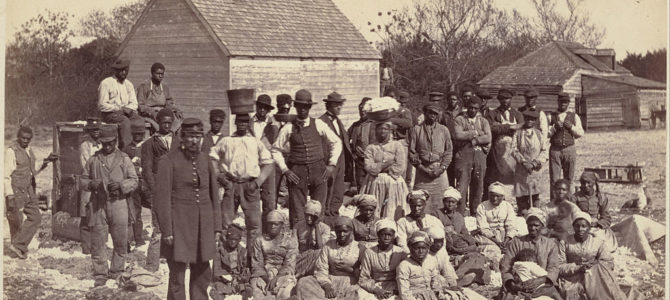

The New York Times has published a series of essays about slavery, race, and American politics under the heading “1619 Project.” These essays cover an enormous amount of terrain: music, constitutional theory, economics, management, ethnic identity, and more.

Many conservatives responded negatively, which at first perplexed me. Slavery was a huge part of American history and has affected every facet of our society. A collection of articles outlining this history seems as good a topic as any to write about.

But zoomed out from the mostly mundane minutiae of individual articles — in the absence of slavery and thus without as much African influence in our music, what would American music sound like? — a larger concern animates the 1619 Project. The project’s central purpose is not simply to educate Americans about the history of labor accounting from plantation to data visualization, or an account of the history of brutal sugar cultivation, but to give a specific narrative about what America is.

The project’s summary makes the aim quite clear: “[The 1619 Project] aims to reframe the country’s history, understanding 1619 as our true founding, and placing the consequences of slavery and the contributions of black Americans at the very center of the story we tell ourselves about who we are.”

Considered this way, the 1619 Project looks very different. It isn’t mostly about helping Americans understand the role played by plantation agriculture in American history. It’s mostly about convincing Americans that “America” and “slavery” are essentially synonyms.

It’s mostly about trying to tell readers they should feel sort of, kind of, at least a little bit bad about being American, because, didn’t you hear? As several articles say explicitly, America, in its basic DNA, is not a liberal democracy, constitutional republic, or federation. It’s a slave society.

Let’s Start with the First Thing Wrong Here

There are a lot of ways to attack this story. But the simplest place to start is the central conceit of the project: that year, 1619.

1619 is commonly cited as the date slavery first arrived in “America.” No matter that historians mostly consider the 1619 date a red herring. Enslaved people were working in English Bermuda in 1616. Spanish colonies and forts in today’s Florida, Georgia, and South Carolina had enslaved Africans throughout the mid-to-late 1500s: in fact, a slave rebellion in 1526 helped end the Spanish attempt at settling South Carolina.

The presence of Spanish power continued to inhibit English settlement of the deep south basically until the Revolutionary War. In some sense, the 1526 San Miguel de Guadeloupe rebellion cleared the way for English settlement of South Carolina.

Of course, when the English did arrive in South Carolina, they struggled to make a living. Early settlers survived on a trade of buckskins and vegetables. It was not until South Carolinians fought the Yamasee Wars of 1715-1717, and sold between 20,000 and 50,000 kidnapped Native Americans into slavery into New England and the Caribbean, that South Carolinians had the capital to buy enough African slaves to get rice and indigo plantations up and running.

But before 1526, slavery was already ongoing in the eventual United States. The earliest slave society in our present country, and our most recent slavery society, was in Puerto Rico. The island’s Spanish overlords were enslaving the Taino natives by 1500. By 1513, the Taino population had shrunk dramatically due to brutal violence and disease. Thus, Spain brought the first African slaves to Puerto Rico.

Chattel slavery in Puerto Rico continued, despite many “Royal Graces” easing life for free blacks and sometimes promising eventual emancipation, until 1873. Even then, slaves had to buy their own liberty. It’s not clear when the last slave was free in Puerto Rico, but it would still have been a fresh memory in 1898 when the United States gained control from Spain.

Slavery in America did not begin in 1619. It began in 1513. Any argument for a 1619 date implicitly suggests that the American project is an inherently Anglo project: that other regions, like Texas, California, Louisiana, and Puerto Rico, have subordinate histories that aren’t really, truly, equal as American origin stories.

In essence, the 1619 date for the beginning of slavery sets up a story of America as an essentially Anglo project that African-Americans were forced into and now claim their share of. But in reality, our country has many origins: French Cajuns and Huguenots, Swedes in Delaware, Dutch in New York, Russians in Alaska, Mexicans in the southwest, Spanish in Florida and Puerto Rico, and of course Native Americans everywhere.

Missing Essential Stories of American Slavery

Native Americans point to another vital reality: African-American identity and a personal history of enslaved ancestors are not synonymous. Some African-Americans, like President Obama, have no ancestry among enslaved Africans in America. Many people enslaved in America, most notably the first slaves, Native Americans, are not of African descent.

Furthermore, “unfree labor” did not end with the end of race-based chattel slavery. Unfree Asian labor in Hawaii and the Pacific west continued almost until the 20th century, while today prisoners of all races are often press-ganged into underpaid labor.

This is not to diminish the African-American experience of slavery: the overwhelming majority of enslaved people in America were of African descent, and the overwhelming majority of people of African descent in America are descended from ancestors who were enslaved. Today, it is reasonable to speak of the African-American experience and the experience of enslavement as essentially and inexorably connected.

But when we talk about history and origins of our society, when we try to untangle the web of events that brought us to where we are today, we have to be more careful. Slavery in America began with Spanish enslavement of Native Americans. In the most enslaved parts of America like South Carolina, slavery largely began with the enslavement of Native Americans.

Like Americans whose origins are in non-Anglo colonies, so too the 1619 Project’s narratives seem to miss a significant part of the legacy of slavery: Native Americans, who remain significantly poorer than African-Americans, less educated, and often with shorter life expectancies. Undoubtedly the 1619 Project’s writers have genuine sympathy for Native Americans. I’m sure they would read my comment here as disingenuous: do I really support Native American rights to land and reparations? For the record, yes, I do.

But beyond that, the 1619 Project bills itself as helping Americans see the real story of American origins. And the real story as the 1619 Project tells it is that slavery began in 1619 with 20 Africans. This isn’t true. This ignores the experience of Puerto Rico, where slavery began earlier, and lasted longer.

Furthermore, a serious accounting for slavery has to wrestle with the experience of Native Americans and Hawaiian islanders, and especially the status of their ancestral lands and sovereign rights. More broadly, to wrestle adequately with the painful historical reality of America’s “labor freedom,” we have to be able to talk about less-than-free Asian migrant workers in California and Hawaii, as well as the indenturehood of the Scots-Irish and subsequent Appalachian poverty.

That these peoples are not treated as subaltern today to the same extent that Native Americans or African Americans still are should not exclude them from a project concerned with history. Plus, many poor whites in Appalachia with accents still experience a version of ethnic subaltern status. We should let them speak without writing it off as white racial grievance.

The United States Was a Footnote in Slavery’s History

Finally, it’s worth exploring the specialness of American slavery. The New York Times is an American publication, so it makes sense to explore the American experience. But a wider-angle lens can help us understand that experience.

Those early slaves in 1619 that The New York Times focuses on arrived on the San Juan Bautista. If that name doesn’t sound English, that’s because it isn’t. It was a Portuguese ship en route to Spanish Mexico. Off the coast of Mexico, it was attacked and captured by English pirates masquerading as Dutch. They sold their enslaved human cargo at Jamestown.

From its earliest moments in the Spanish colony of 1526, Puerto Rico in 1513, or even Jamestown in 1619, the truth is that America was a footnote to a larger world of slavery. We did not invent this evil. We enthusiastically embraced it.

But when we explain the role played by slavery, we have to recognize that slavery is no more “native” to the American experience than, well, anything. We stole the first slaves from Portugal. Slavery struggled to “take off” in much of the South because managing a plantation is extremely technical and complicated, and many Americans were not good at it. It was an influx of experienced human traffickers, slave-torturers, and large-scale agribusiness experts from Haiti and other Caribbean colonies in the 1700s that gave much of the Deep South enough “expertise” in the abuse of humanity to develop a thriving slave economy.

Lacking much home-grown ingenuity, U.S. slavery had reached an economic bottleneck by the 1780s: tobacco destroyed soil nutrients and was unsustainable, rice and indigo couldn’t be widely cultivated, the colonies had a bad climate for sugar, and the de-seeding process for “upland cotton” was prohibitively expensive, meaning only Caribbean-style “Sea Island” cotton could be cultivating on a large scale. It took a clever abolitionist New Englander, Eli Whitney, to invent the cotton gin.

He thought he was sparing slaves the tedious work of de-seeding Sea Island cotton. He didn’t realize he was opening the door to cotton cultivation, and thus a slave economy, throughout the interior south.

In other words, the history of slavery is not one of some evil creativity unique to Americans. We emulated models of slavery pioneered elsewhere. We “improved” on it, of course; the American zeal for “efficiency” drove escalating brutality (although Anglo cotton plantations never reached the perigee of inhumanity achieved by the Francophone sugar plantations of Haiti and Louisiana).

We are covered in the blood-guilt of millions of enslaved people. But when we try to tease out the strands of American identity, slavery, like so many other pieces of America, is an immigrant. To the southern Tidewater colonies, to their eternal ignominy, it was a welcome one. But many inland southerners and to many northerners, slavery was a baleful evil they—perhaps incorrectly—saw as forced upon them by Britain.

America’s Story Is of Increasing Refusal to Tolerate Slavery

This story of slavery as something somehow “foreign” to many Americans will read as a bit much to many enthusiasts of the 1619 Project. If Americans were so unhappy with slavery, why didn’t they abolish it?

My answer is simple: we did. At the risk of historical absurdity, it must be noted that when Georgia was founded in 1732, slavery was banned, making it the first place in the Western hemisphere to ban slavery. But alas, the appeal of plantation wealth was too great, and by 1752 the King George II (the father of the George we rebelled against) had taken over Georgia as a royal colony, and instituted slavery.

Thus, in 1775, there was no free soil anywhere in the Western hemisphere. Slavery was a universal law. While I cannot say for certain, it is possible there was no free soil in the entire world—that is, no society that categorically forbade all slavery.

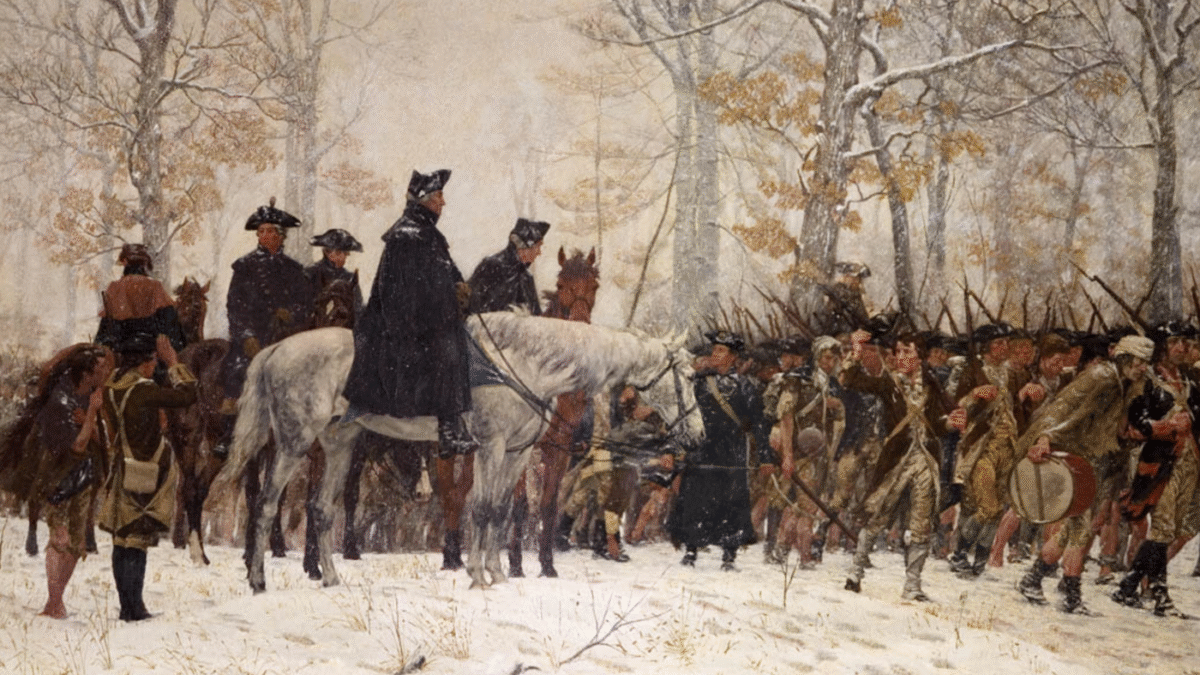

But then something changed. Revolutionary agitation led to war in 1776, and by 1777, Vermont’s de facto secession from New York and New Hampshire created the first modern polity in the western hemisphere to forbid the keeping of slaves. In 1777, war with Britain was barely begun.

Vermont was hardly secure. But in their opening salvo to a watching world, Vermonters made clear what they thought America was about: liberty for all mankind. In 1780, still amidst the guns of war, Massachusetts’ constitution rendered enslavement legally unenforceable, and the judiciary soon abolished it.

Numerous states followed suit. Their exact procedure varied: some immediately emancipated all slaves, some used gradual emancipation, and some tried other “creative” methods. But the point is that, unlike in some early-abolition countries like France or Peru, or in Georgia’s early free status, abolitionism stuck in America.

The fledging Confederation Congress set aside the majority of the land ceded from Great Britain as free soil. Despite concerted attempts by southerners to “flip” both Indiana and Illinois as slave states, the early commitment to abolition held fast. Likewise, the United States was the second country, by a matter of weeks, to outlaw the international trade in slaves, after Great Britain. Countries like Spain and Portugal continued thereafter to trade slaves for decades, and Brazil did not outlaw slavery until 1888.

In other words, Americans were early adopters of abolition. We were the first to establish formally abolitionist constitutions and states, the second to ban the trade in slaves, and middle-of-the-pack in achieving uniform abolition of slavery.

No, Slavery Does Not Define America

Undoubtedly, we still must atone for much. Slavery lasted longer than any conscience should have allowed. The Christian consciences of America’s founders should have stirred them to intolerance of a single day of slavery on our shores. Alas, it did not. This is a moral failure.

But the history of America is not defined by some romance with enslavement, as the 1619 Project seems to suggest. The high points of American history, the ones we celebrate, memorialize, emphasize, and teach to our children as who we are, and as examples to be emulated, are moments of liberation.

The Jamestown founding of America has no national holiday, in part because most Americans sense that slavers looking for gold is, while part of our history, not the part we want our children to emulate. But when Thanksgiving comes, we celebrate the Plymouth colony: religious dissidents seeking liberty.

While fictionalized to some extent, it speaks well of Americans that Thanksgiving is presented as a collaboration between religious dissidents and Native Americans: the story we tell to our children, the example we hold up as how Americans ought to live, is that they ought to tolerate diversity of opinion and actively seek cooperation and peace with extremely different neighbors.

The history of America is indelibly marked by the sin of enslavement of many peoples, African and Native American. To remind Americans of this, and to carefully trace how slavery has impacted our society today, is a good thing.

What Defines Us Isn’t Our Worst Moments

America has been blessed by courageous black voices for centuries reminding the mostly white body politick of this sin, and calling us to repentance and reconciliation. This call to repentance has often come at considerable cost to those African-Americans who speak up in a society that, like all human societies, dislikes being reminded of its sins.

Much of the straight history presented in the 1619 Project is good, insightfully presented, and will be news to many Americans. As a Lutheran, I applaud the authors of the 1619 Project for confronting Americans with the law of God, holding a mirror to our sins, past and present.

Yet I also wonder if that mirror of our ugliness is truly who we are. Is a person who he is in his darkest moment? If we record people in their most vicious hour, when they most succumb to the temptations that nag on all of us, is that video who they truly are?

I think not. I think we are not defined by who we have been, and we are not defined by our worst national sins. The American story is not a story of a country defined by slavery, but a country defined by trying, in fits and starts, with faltering and hesitance, but also with moments of glory, to figure out what it means to live with liberty and self-government.

It is altogether fitting, then, to conclude as a great, glorious, flawed, struggled, penitent, but courageous American concluded, when discussing what it meant to be American in a time of great division. “We are not enemies, but friends. We must not be enemies. Though passion may have strained it must not break our bonds of affection. The mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battlefield and patriot grave to every living heart and hearthstone all over this broad land, will yet swell the chorus of the Union, when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature.”