The following is adapted from the book Lessons in Liberty: Thirty Rules for Living from Ten Extraordinary Americans.

Happy 273rd birthday to James Madison, the most egregiously underappreciated, sadly uncelebrated, and unfairly unsung American in the history of the United States.

Consider the list of his towering achievements: Father of the American Constitution, formulator of American federalism, collaborator of The Federalist Papers, de facto doula of the Bill of Rights, and the fourth president of the United States.

Yet there is no significant monument in Washington, D.C., celebrating Madison’s titanic contributions to the American self-government experiment. No American temple featuring quotes chiseled in marble, no miniaturized version of his home, no statue strategically placed on the National Mall, no allusion to membership in the American Mount Olympus.

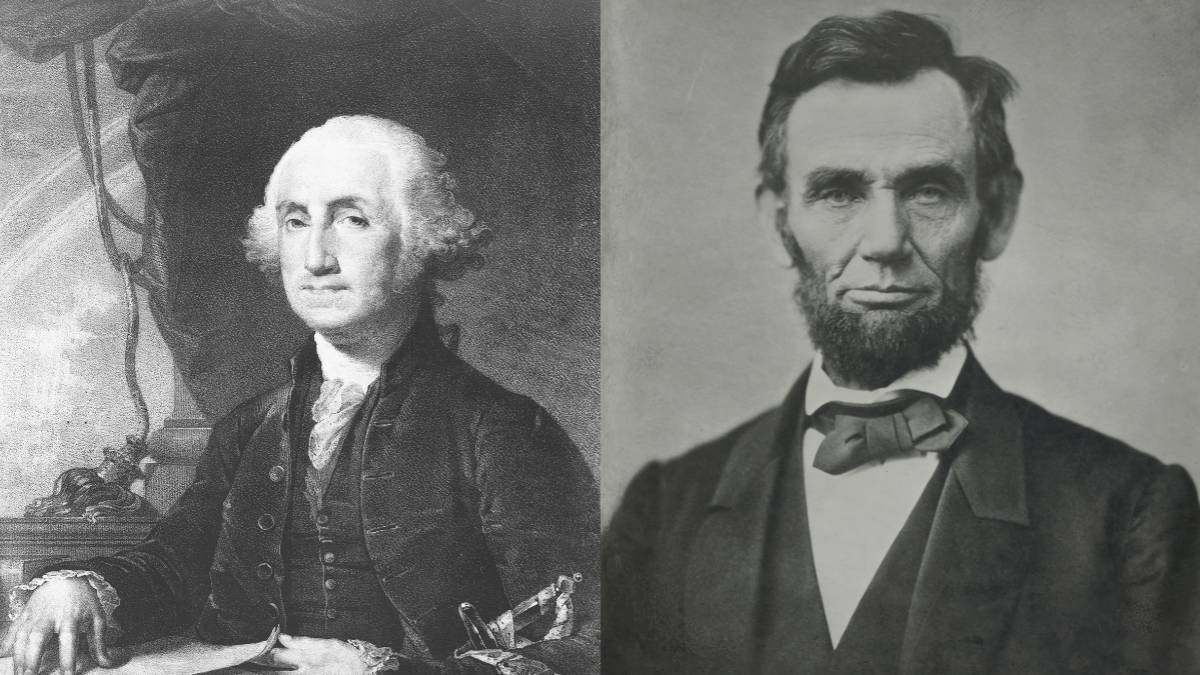

While Americans, especially schoolchildren yearning for a day off in the middle of February, are well acquainted with the twin birthdays of Lincoln and Washington, tragically few know of Madison’s March 16 birthday. Madison isn’t molded onto Mount Rushmore, nor is he headlined on Broadway every evening. He is ignominiously ranked in the middle of the pack by presidential historians, and unlike Washington and Franklin who are forever loved and celebrated, or Adams and Hamilton who have both enjoyed a modern renaissance in the past two decades due to sympathetic and best-selling historians, Madison’s place in the pantheon of American titans is decidedly underwhelming.

Perhaps the best way to honor Madison on his birthday is to recognize that we have much to learn from him today, for his list of titanic achievements did not happen by accident. In fact, his successes should echo today, not merely because they helped to forge the civilization we ultimately became, but because we can live better and more meaningful lives by following his inspiring example.

Consider these Madisonian lessons:

1. Be the Most Prepared Person in the Room

Perhaps it is dull, lacking in both dramatic flair and flamboyant bombast, but if Americans want to understand how Madison was able to achieve so much, the central reason is that he worked harder, studied more, and was always willing to put in more hours of concentrated labor than others.

Indeed, it is not hyperbole to suggest some of the most consequential gatherings in American history were steered to their eventual outcome by the grand power of Madison’s work ethic. Beyond the revolutionary political ideas or the historic constitutional schemes that were to come, merely getting Washington to attend the Constitutional Convention was perhaps the greatest boon of all. Madison worked hard to coax, flatter, and convince “the indispensable man” to come to Philadelphia for a simple reason: Washington’s mere presence bestowed the gathering with legitimacy and infused it with popular credibility.

In addition to imbuing the gathering with legitimacy, the task before Madison was daunting. His undertaking was to harness the lyrical truths of the Declaration of Independence and institutionalize them into a coherent system of government. Much of Madison’s preparation during the spring of 1787 was geared toward avoiding the bellicosity, belligerence, and bloodshed of a thousand years of European history in which neighboring nations of roughly coequal size constantly found excuses to go to war with one another.

Madison’s voracious efforts leading up to the Philadelphia convention required that he embody the Janus-like ideal of possessing two faces at once — policy wonk and philosopher, statesman and social scientist, historian and hard-nosed realist.

2. Be Willing to Change Your Mind

If Madison’s work ethic helped to birth the Constitution, it was his willingness to change his mind that is largely responsible for the American Bill of Rights.

At first, Madison argued that a Bill of Rights had very little to do with the mandate of the delegates at the Constitutional Convention. Their task in Philadelphia, as Madison saw it, was to create new institutions of government, to enumerate what powers these institutions possessed, to decide how these institutions worked together, to explain how one is elected or appointed to these institutions, and hope that the constitutional framework achieves the ultimate goal of justice.

As time went on, he softened his reticence toward a Bill of Rights.

As the state-by-state ratification process progressed, it became obvious that the absence of a Bill Rights was the strongest objection lodged by the Anti-Federalists. By eventually acquiescing to the demands for a Bill of Rights, the strategically astute Madison realized he was now blunting the primary argument against his beloved Constitution and preventing his greatest fear from coming true: a second Constitutional Convention, which he knew would undermine the first.

3. Be Generous — Don’t Worry About Who Gets the Credit

On countless occasions throughout his extraordinary but underappreciated career, Madison was willing to put in the hours and endure the grind of hard mental labor, but when the moment to step into the spotlight arrived, to bask in adulation or acclaim, he would often defer to others. He never worried about who got the credit; he was results-oriented without being a Machiavel or a deceiver.

After months of preparing the Virginia Plan as a blueprint or starting point for the Constitutional Convention, when the time came to present his plan, he allowed the governor of Virginia, Edmund Randolph, to present it instead.

After the convention was over and the time for the ratification process began, Madison’s first inclination was not to attend the Virginia ratification debate. Instead, he had to be persuaded that his attendance was both necessary and advantageous to the cause of the new Constitution.

But nowhere is Madison’s propensity for stepping aside or working behind the scenes more pronounced than in his friendship with Jefferson. While Jefferson is perhaps the most celebrated American to have ever lived, behind much of this success is the genius of Madison. They drafted the Virginia and Kentucky resolutions together in opposition to John Adams’ Alien and Sedition Acts. Most significantly, Madison worked steadily behind the scenes to help forge the new Democratic-Republican Party. When the party successfully defeated Adams in 1800, the first president representing the new party was Jefferson, not Madison.

Madison’s significance in our history and the lessons his life provides to Americans today should be both loud and large. In an era of potent political turmoil and personal strife, we ignore them to our and the nation’s detriment.