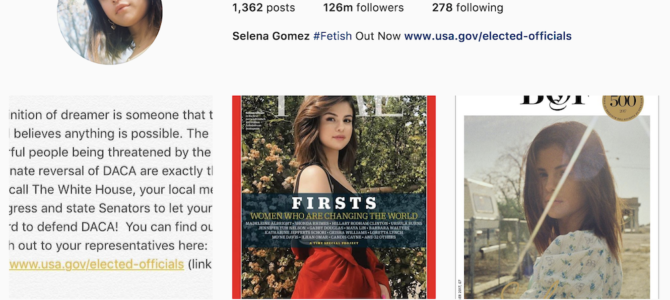

In an interview with Time magazine this week, Selena Gomez shared her experiences growing up with social media and becoming a pervasive celebrity presence through the medium of Instagram. Gomez is the most popular person on Instagram, with more than 100 million followers.

While she speaks positively of the experience, arguing that true strength lies in becoming “vulnerable,” she also notes the negative impact social media can have on one’s life: “I see a disconnect from real life connections to people, and that makes me a little worried. I do think social media is an amazing way to stay connected, to learn more things about what’s going outside your little bubble, but sometimes I think it’s too much information.”

Vulnerability Shouldn’t Always Happen Virtually

It’s become very popular for people to post diatribes, confessionals, and feel-good stories on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter. These quickly become viral fuel for our collective social media fires. We like hearing moving stories; we like feeling close to people. Sometimes, we just really like feeling outraged. Viral vulnerability foments and feeds these desires.

But how does viral vulnerability serve the actual human beings who are subject of these stories? Their plight, outrage, or snark might result in a highly successful GoFundMe campaign—an effort to stamp out injustice, right wrongs, or support someone who’s suffering. But often, the virtually mediated nature of these contacts means that we can’t truly help in the way we ought to. In cases of outrage, we don’t always receive the whole story. Social media gives us the opportunity to connect, but it fosters weak ties, not strong ones.

Viral vulnerability, it must be noted, is a curated thing. Gomez’s vulnerability is beautiful: replete with soft filters, lovely makeup, and pretty clothes or lingerie. It’s not raw, uncensored. And it should not be: there is no reason a young celebrity should expose the deepest parts of her life to 100 million strangers. But when Gomez tells youth that “strength lies in being vulnerable,” especially in the context of discussing social media, she is suggesting that they, too, should bare their (carefully curated) souls to a wider world.

There are circumstances and conversations that go viral with good reason. There’s no denying that. But so often, our impulses online become subconsciously influenced by that desire for fame, popularity, the potential to “go viral,” to become our own clickbait. We become vulnerable with populations we should not become vulnerable with—out of loneliness, perhaps, or a deeper desire for affirmation and respect. But such mediated vulnerability can have a deeply deleterious impact on our relationships online, especially amongst a younger generation.

As Olivia Laing noted in an article about loneliness for The Guardian in 2015,

This is where online engagement seems to exercise its special charm. Hidden behind a computer screen, the lonely person has control. They can search for company without the danger of being revealed or found wanting. They can reach out or they can hide; they can lurk and they can show themselves, safe from the humiliation of face-to-face rejection. The screen acts as a kind of protective membrane, a scrim that allows invisibility and transformation. You can filter your image, concealing unattractive elements, and you can emerge enhanced: an online avatar designed to attract likes. But now a problem arises, for the contact this produces is not the same thing as intimacy. Curating a perfected self might win followers or Facebook friends, but it will not necessarily cure loneliness, since the cure for loneliness is not being looked at, but being seen and accepted as a whole person – ugly, unhappy and awkward, as well as radiant and selfie-ready.

Friendship In An Online Age

One thing Gomez recently pointed out in another interview is that she only has a sparse handful of close friends—despite her online notoriety and immense social following:

‘You have to figure out the people that are in your circle. I feel like I know everybody but have no friends,’ Gomez told Business of Fashion, suggesting that online popularity doesn’t always translate into real-life relationships. ‘I have like three good friends that I can tell everything to, but I know everyone. I go anywhere and I’m like, ‘Hey guys, how’s it going?’ And it feels great to be connected to people, but having boundaries is so important. You have to have those few people that respect you, want the best for you and you want the best for them. It sounds cheesy, but it’s hard.’

In the above quote, Time writer Raisa Brunernotes that “online popularity doesn’t always translate into real-life friendships.” This seems obvious: but to a lot of young people in the post-millennial (or iGen) generation, it isn’t. It’s easy to measure popularity and happiness by the hundreds (or even thousands) of friends we have on Instagram, Snapchat, or Facebook. It’s easy to see a carefully curated, and beloved, public persona as an emblem of success.

But Gomez points out an important truth here, to a generation that badly needs it: friendship isn’t popularity. And friendship rarely blossoms in carefully curated circumstances. It only happens in face-to-face, intimate contexts. Loneliness in the real world is less about “being seen,” and more about seeking “withness”—having a comrade, a neighbor, to be with. True friendship is altogether different from a “following.” While it can happen online, it is unlikely to grow in a public setting. Friendship requires intimacy, trust, loyalty, confidence. Those are private virtues, not public ones.

Friendship Requires Privacy And Place

Somehow, our online age has convinced us that transparency and vulnerability should be public acts. Quiet confidence and private trusts are not valued as they used to be. But friendship is a starved, shadowy thing without them.

Wendell Berry once told me in an interview, “Community is not made just by communication. It is a practical circumstance. It is composed of people who have a place in common. But it is made by people’s willingness to be neighbors, good and faithful servants, to one another. It survives by its members’ recognition of their need for one another, if only to keep the small children from getting lost or run over, or to keep their trash out of the streams and roads. My guess is that a healthy community would be indivisible from its own, its local, economy.”

The sort of friendship Berry is describing here isn’t ultimately about the self, its transparency and vulnerability. It’s about practical virtues, such as service and neighborliness. These virtues cannot be cultivated, long-term, over a long distance. And without them, it’s unlikely that a friendship could (or should) grow into deep vulnerability and openness. Loving acts of service are, at least to some degree, the prerequisites for deep intimacy. They serve as the assurance that you have, in Gomez’s words, people in your life who “want the best for you and you want the best for them.”

How To Foster Friendship In A Digital Age

This isn’t to say that friendship cannot be cultivated online, or that we should discontinue all our social media accounts. It means, however, that our use of social media is more likely to be successful when it’s used to curate and foster face-to-face meetings and real presences. Facebook’s groups and events capabilities are a valuable way to foster friendship: they help people to gather physically and have actual conversations, away from the public eye. Instagram’s private messaging, similarly, affords opportunities to share sweet moments in a more personal way with family and friends.

There’s a time and place for social media, perhaps. But as Gomez points out, it doesn’t serve to foster real friendship. True friendship, true vulnerability, can only happen outside the constrains of public Facebook statuses and perfect Instagram or Snapchat selfies. It happens with real people, in real time.